By Manuel “Bobby” Orig, Director, Apo Agua

HOW TO MAKE SMART DECISIONS By NOREENA HERTZ

This game-changing book empowers readers to become confident, independent, wise decision-makers – savvy to how our emotions, moods, and habits can trip us up.

An investor wonders whether to put his money into the stock market or to keep it in a savings account. A patient is torn between opting for surgery and trying an experimental drug therapy. A college-bound student questions whether to take on debt to attend an Ivy League school or to choose a public institution with low tuition.

We face momentous decisions with important consequences throughout our lives. We never have had access to information and expertise, yet this data deluge has become a double-edged sword. Which sources of information are credible? How can we separate the signal from the noise? Whose advice can we trust?

All of these questions are reasons for us to become empowered decision-makers capable of making high-stakes choices ourselves.

It’s time to make decisions with our eyes wide open – for the sake of our health, our wealth, and our future security.

Praise for the book:

Witty, well-researched and practical, Eyes Wide Open is an invaluable guide for anyone facing tough decisions in today’s complex world. Hertz alerts us to the land mines we need to avoid when making tough calls and provides clear and effective recommendations overall to help us make better and wiser decisions.

–DOMINIC BARTON, global marketing director, McKinsey & Company

About the author:

Noreena Hertz is a bestselling author, academic, and thinker who has been described by Vogue as “one of the world’s most inspiring women.” Hertz has given talks for TED and the World Economic Forum, and she also advises a range of major corporations. She is associate director at the Centre for International Business and Management at the Judge Business School, University of Cambridge.

THIS DECISION WILL CHANGE YOUR LIFE

It’s Monday morning.

In Washington, the President of the U.S. is sitting in the Oval Office assessing whether or not to order a military strike on Iran.

In Idaho, Warren Buffet is deciding whether to sell his Coca-Cola shares or buy more.

In Madrid, Maria Gonzalez, a mother is trying to work out whether to let her baby continue crying until he falls asleep, or pick him up and soothe him.

The author is sitting by her father’s bedside hospital trying to decide whether she should let the doctor operate, or wait another twenty-four hours.

We face momentous decisions with important consequences throughout our lives. Difficult and challenging problems that we are given the sole responsibility to solve.

On top of this, we have to make up to 10,000 trivial decisions every single day, 227 just about our food (study by Cornell University researchers Brian Wansick and Jeffrey Sobal). Caffeinated or decaf? Small, medium, large or extra large? Cream or milk? Brown sugar or sweetener.

If you make the wrong choice when it comes to your coffee, it doesn’t matter very much.

But make the wrong choice when it comes to your finances, your health, or your work, and you could end up sicker or poorer, or lose your job. And if your decision relate to others – your parents, your children, your country, or your staff – the choices you make can irreversibly impact the direction their lives will take too. Not only today, but in the months and days ahead.

This book is about how to make better choices and smarter decisions when the stakes are high and the outcome really matters.

THINK YOURSELF SMARTER

It’s actually very surprising how little we think about the quality of our decision-making and how we could improve it.

For the sake of our health, our wealth and our future security, we must take it upon ourselves to challenge the way we make decisions. It’s a matter of self-empowerment.

If we do not want to be victims of a future that others dictate to us, we need to get better at making choices with our eyes wide open, our brains switched on.

This means getting better at collecting, filtering and processing information, getting smarter at establishing who to trust and whose recommendations to take on board, getting more adept at analyzing different options and weighing up divergent opinions. It also demands that we forge a clearer sense of how it is we come to our decisions – that we understand how our emotions, feelings, moods and memories affect our choices. And that we better know and understand our environment, so that we can master its particular challenges.

HOW TO BE AN EMPOWERED DECISION-MAKER

The context in which we have to make decisions is, to say the least, challenging.

And yet, we still have to make choices. We still have to decide which doctor’s advice to follow. The president of the U.S. still needs to decide whether to strike Iran. The mother hearing her baby cry still needs to decide whether to pick him up or leave him to cry through the night alone. We still have to make decisions, important, life-changing decisions, regardless of how distracted we are, how much data swirls around us, how unpredictable and uncertain our world now is.

Over time, we’ve developed ways to do just that, developed short cuts and coping strategies – some conscious, some not – for navigating this difficult terrain. Strategies for gathering information and then processing it in ways that fit with the realities of our distracted, deluged, disordered lives.

We need to take more control of our decisions and how we make them. We need to become empowered thinkers.

By learning from decision-makers who’ve sometimes got things right and sometimes got things very wrong, we will get a better sense of those traits and strategies that can help us be good decision-makers, as well as the moves that can serve us ill.

What is impossible to do is to give you one over-arching, catch-all strategy to follow. There is a no one-size fits-all decision-making template for all of us, at all times. Human life is too complex for that.

Instead, what the author hope to deliver is a “decision-making tool kit.” A kit that will enable you to interrogate your own decision-making habits and investigate the information you are given. A kit with the tools that will empower you to make decisions in radically different ways from how you may have been making them until now.

Because ultimately, this book is about empowering you.

The goal of this book is to empower all of us to become more confident, more independent and wiser thinkers and decision-makers.

THE TIGER AND THE SNAKE

In 2005, the prominent American cognitive psychologist Professor Richard Nisbett began an extraordinary experiment.

After some careful planning, he showed a group of American students and a group of Chinese students a set of images for just three seconds each. The images were pretty varied: a plane in the sky, a tiger in a forest, a car on the road.

How would the American and Chinese students view these images, the Professor wondered. Would they see them differently? Would they see the same things? If there was a snake in the ground, would the Americans or the Chinese notice it?

The differences between the two sets of students were immediately apparent.

The Americans focused on the focal object: the plane, the tiger, the car. They pretty much fixated on these, and barely looked at the background.

The Chinese, on the other hand, took longer to focus on the focal object – 118 milliseconds longer. And once they had done that, their eyes continued to dart around the image. They took in the sand, the sunlight, the mountains, the clouds, the leaves.

So if there was a snake on the ground behind the tiger, it would be the Chinese, not the Americans, who would see it.

ALL THAT GLITTERS…

In a complex world of hidden dangers and fleeting opportunities we all need to be able to see snakes as well as tigers.

We have to understand that the picture we see at first may not give us all the information we need to make the best possible decision. We need to learn to see beyond what we are culturally and conveniently attuned to focus on.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t ever act until we’ve gathered every single piece of information out there that may be relevant to our decision. That would be excessively time-consuming, and our brains wouldn’t be able to cope with all that data.

But what the tiger and the snake experiment tell us is that the information we’re most prone to focus on may only give us a very partial story, or a fragment of the truth, and therefore risk misleading us. Being aware of this, and adjusting accordingly, would make a profound difference to the decisions you make.

All of us need to get better at thinking about the whole picture. We need to look beyond what is immediately obvious or easy to see. For if we are to see a snake as well as a tiger, if we are able to see what it is we need to see, we must remember that the information that glitters most brightly may not actually be what will serve us best.

THE DANGER OF RELYING ON POWERPOINT

Sometimes it is not our fault that we’ve only got partial vision.

Edward Tuftee, an American statistician and Professor Emeritus of Political Science, Statistics and Computer Science at the Yale University, knows this all too well.

Tuftee was hired by President Obama to keep an eye on how his $787 billion stimulus package was being spent. In his academic career he has undertaken substantial research into how information graphics impact on decision-making.

One case he has looked at in real depth is the Columbia Space Shuttle disaster of February 2003. Seven astronauts lost their lives when their NASA spacecraft disintegrated shortly before the conclusion of a successful sixteen-day mission.

It is now well known that a briefcase-sized piece of insulation foam from the Shuttle’s external fuel tank collided with its left wing during take-off, meaning that the Shuttle was unable to shield itself from the intense heat experienced during reentry to the earth’s atmosphere.

But the official investigation also revealed a story that is both fascinating and curiously everyday in its nature.

A key underlying factor that led to the disaster was the way in which NASA’s engineers shared information.

In particular, the Columbia Accident Investigating Board singled out the “endemic” use of a computer program. A program we more usually associate with corporate seminars: Microsoft PowerPoint.

The investigators believed that by using PowerPoint to present the risk associated with the suspected wing damage, the potential for disaster had been significantly understated.

In other words, the very design tools that underpin the clarity of PowerPoint had served to eclipse the real story. They had distracted its readers. They had served to tell a partial, and highly dangerous story.

THE CULT OF THE MEASURABLE

It’s not only particular forms of presentation that can blinker our vision.

One type of information often dominates our attention – numbers. This in itself can be problematic.

Numbers can give us critical information – if we want to know whether to put a coat on, we’ll look at the temperature outside; if we want to know how well our business is doing, we’ll need to keep an eye on revenues and expenses; and if we want to be able to compare the past with the future, we’ll need standard measures to do so.

But the problem is that the Cult of the Measurable means that things that can’t really be measured are sometimes given numerical values.

Can a wine be 86 percent good? That doesn’t sound right, but this multi-billion-dollar-industry doesn’t agree. Robert Parker, probably the most famous wine critic in the world, ranks wines on a scale between fifty and one hundred. And winemakers prostrate themselves before him, praying for a ninety-two or above, because such a number practically guarantees commercial success, given how influential Parker’s ratings have become with wine drinkers.

Yet what really is the difference between a rating of ninety-two and an eighty-six? How can we tell how that six-point difference mean?

So before you make a decision based on a number, think about what that number is capturing, and also what it is not telling you.

MAKING SMARTER DECISIONS

If we are to make smarter decisions, we need to make sure that we are not overly swayed by what we’ve seen most recently, or by the information that’s most easily available, or by our initial assessment, or by what it is we most want to hear.

We must also force ourselves to actively search for information that challenges our preconceived idea.

We have to treat each new situation as independent, and each new piece of information as potentially game-changing.

And when making assessments, we must question not only whether things are as we think, but also what else they could possibly be.

The head of one of Europe’s leading hedge funds – a fund that succeeds or fails on the basis of its analyst’s assessments of the industries states that he sees one of his primary roles as that of “Challenger in Chief,” as the person who niggles his staff to focus not only on the evidence that confirms their initial assessment or that they want to hear, but also to actively look for data that will contradict or refute it.

HOW TO SEE WITH EYES WIDE OPEN

To make smart decisions we need the right information to guide us. That is a given.

This means being aware of how instinctively tunnel-visioned we can be, of how some information glitters much more brightly than others – some of which may well turn out to be fool’s gold.

This means becoming more conscious of the way we are drawn to what’s most familiar or most obvious, or closest to what we want to hear. Of how little attention we pay to what we don’t want to know. Of just how caught up in our past we can be, and how we can disable our ability to process the presence or imagine the future.

Being aware is a start. But there’s more that we can do to ensure we see with eyes wide open.

One thing we do is to give ourselves more time – time to gather both the right information, and to consider it. In order to think well, especially in hectic circumstances, you need to slow things down to avoid making cognitive errors.

You need time to ask yourself what you may not have thought about, time to consider alternatives, time for your eyes to dart around the picture.

Time pressure encourages tunnel or distorted vision, while the best ideas often emerge after a reflective pause.

Before moving on to the next step, it’s also worth reminding ourselves of the following:

- First, that the further into the future the outcome of your decision will play out, the less likely that what worked before will prevail. It’s a basic law of probability – so if you can make your decision as late in the day as possible, do.

- Second, that decisions are best made with built-in flexibility. So, if possible, don’t fix yourself to Plan A. Try whenever you can to have Plans B, C and D in your pocket

- Third, bear in mind that in order to work from the best intelligence as possible, you need to make assessments on an ongoing and continuous basis. This means keeping your eyes on the present and the future, not only on how things once were. Actively ask yourself, “What is different now?’ “What could be different tomorrow.” And then think through the implications of this for the decisions you’re currently making and the information you’re presently seeking out.

BEWARE OF ANCHORS

In Germany, a group of 177 senior trainee lawyers were asked to put themselves in the position of a trial judge having to pass sentence in a rape case.

They were given key aspects of the case to evaluate, including witness statements, experts appraisals and copies of the penal code related to the incident.

However, there was a twist. As they were appraising the case in the courtroom environment, the “trial judges” were interrupted by a heckler. Although this is a common occurrence in emotionally charged legal cases, in this case it was a set-up. The heckler was an actor. And the judges were exposed to one of two types of heckler.

The first pretended to be a boyfriend of the victim, and shouted out to the court, “Give him five years!” The second acted as a friend of the accused, and yelled, “Let him go free!” The judges were then asked to reflect briefly on the interruption and pass sentence.

The results were pretty astonishing.

Even though our judges knew that they should ignore the heckler’s interruption – especially as they understood that it was a biased opinion, with the heckler pushing either for leniency or for harsh sentencing depending on his supposed relationship to the accused or the victim – there was a marked variance in response between the judges who were exposed to the “Give him five years” heckler and those interrupted by the “Let him go free” one.

Judges who were confronted with the “Give him five years” remark pronounced on average a sentence of thirty-three months. Those who were confronted with the “Let him go free” remark pronounced on average sentence of twenty-three months – almost a third less in length.

The judges had “anchored” their sentencing decision around a biased interjection from a heckler, and had set aside much of the other information provided to them.

Even if such highly trained information evaluators can make mistakes like this, it’s not surprising to learn that we are all prone to similar “anchoring” errors.

In each of these cases, the higher the number of people unconsciously fixated on, the higher the number they gave as their decision. That is why real-estate agents will usually show you the most expensive house first – so that others will seem cheap by comparison; or more pertinently, will seem cheap when compared to the “anchor point” they have established in your mind.

So how can we avoid unwittingly basing a decision on an inappropriate number? For we are often asked to make decisions that, whether by manipulation or chance, involve anchors lodged in our minds.

We need to reflect upon whether a number is actually the right thing to be focusing on at all – to remember that not everything that can be counted, counts.

Assuming that in this case the number is relevant, one thing you might want to try is to ask yourself whether there is anything you might be anchoring your decision on. And if there is, whether that anchor might be inappropriate or misleading. Studies show that simply by asking ourselves questions we are able to override the anchor’s effects.

RECLAIM THE TRUTH

The bad news is that it’s not enough to give yourself a general note to avoid basing your decisions on anchors, sensory cues and rhetoric. This tends not to make any difference at all.

The good news is that there are ways to regain control of your unconscious, at least to some degree. There are active thinking strategies that do deliver if you suspect you might be being spun or played, or that you might inadvertently be basing your decisions on an anchor.

One such strategy is to get into the habit of imagining an alternate scenario, in which your cue or anchor, isn’t present. How would you respond?

For example, if you are about to put an offer in for a car in an auction, don’t just anchor your offer automatically on the guide price. Instead, ask yourself what offer you would have to put in in you were thinking completely independently.

Studies show that simply by posing such “imagine if” questions, which allow us to consider alternative explanations and different perspectives, we can distance ourselves from the frames, cues, anchors and rhetoric that might be affecting us. Liberated from these tricks and triggers, we can consider information through a more neutral, less emotive, more analytical and nuanced lens.

BECOME YOUR OWN CUSTODIAN OF TRUTH

HOW TO PICK THE RIGHT EXPERT

The truth is malleable; you just need to pick the right experts.

—Gillian Flynn

Decisions as diverse and important as to whether to have surgery or a vaccination, whether to take on more staff or increase your advertising budget, will have experts of different hues trumpeting diametrically opposed positions.

So when the stakes are high, the first step is to remember that you may need to listen to a number of different expert views before you decide choosing.

But then you have to work out how to pick between different experts. How do you know which to trust over another?

One generally acceptable strategy to adopt is this: do everything you can to become an expert yourself. If it’s a decision that really matters, you need to build your own knowledge base, think for yourself, be ready to know what the right questions are, and what kind of answers you might receive. You’ve got to make sure you understand what it is your experts are telling you, what they’re recommending or advising, so that you can properly consider their steer.

CAST YOUR NET WIDER

Traditional experts come to the table with particular skills and knowhow. These are valuable. Yet all too often they make their pronouncements from on high, without sufficient mindfulness of context or local conditions.

Lay experts, on the other hand, necessarily have their feet on the ground. This means that they are capable of delivering insights that those looking down from up top, however, qualified, may never discover or volunteer.

Experience is not the poor relations of expertise.

PhDs and fancy titles are all very well, but they do not necessarily deliver better insights.

So if we want to make better decisions it is not enough that we challenge and better scrutinize traditional experts, we also need to expand our notion of who it is we turn to for advice and guidance.

We need to value what Nobel Prize-winning economist Friedrich Hayek described as “local” knowledge – the dispersed wisdom on the ground. This means casting our nets much wider than we are traditionally prone to do, and seeking out the most experienced and best-placed lay experts, wherever they happen to be.

It’s not rocket science. If it is caring for children that you want to get insights into, parents will probably have something valuable to share. If it is new product innovations you are considering, tap into the insights of the product’s existing fans.

More generally, if it is issues at work you are trying to get a perspective on, there’s a significant constituency you might not be deploying effectively – your workers, or the teams you personally manage. They might just have the answers that expensive management consultants, swooping in for a few weeks with no direct experience, are less likely to discover.

ARE YOU WHO YOU SAY YOU ARE?

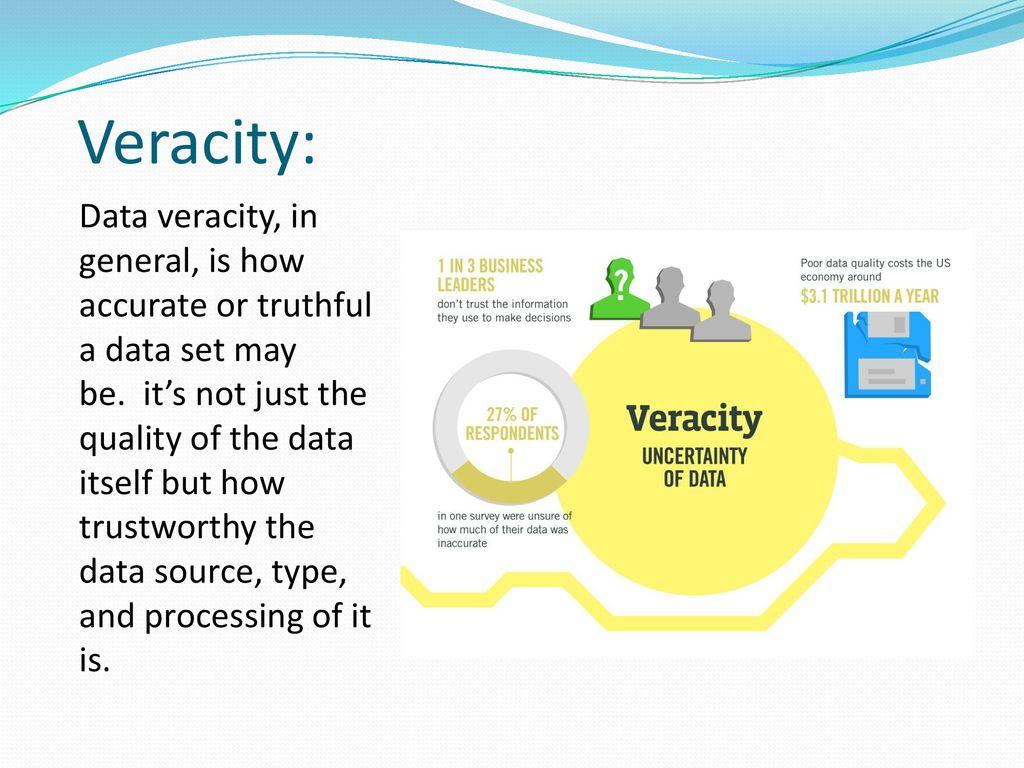

In an era in which we will increasingly have the opportunity to navigate the information landscape ourselves, we need to be careful.

For if we are to maximize the value of our new online world of blogs and posts and searches in order to make smarter decisions, we need to feel confident that they can be trusted.

In the absence of traditional gatekeepers, the responsibility will increasingly fall on us to establish the veracity and credibility of our sources—if we don’t pay attention to this, no else will.

In an age in which most of what we come across is anonymous, with even these sources that are credited likely to be unknown to us or unproven, outing the outright liars – particularly those who have invested huge amounts of time or money in their duplicity – will always be extremely tricky, especially given the volume of information we now have to sift through.

But there are some simple hoax-detecting steps you can take.

If it’s a personal testimony you’re thinking of relying upon to make a decision – a blogger’s, or someone you’ve come across in a chatroom or an online forum – is there a way to contact them directly via another medium? By telephone? Email? In person?

If this person claims to be in a position of authority – like a WebMD gynecologist – are they to be found in the directory of the hospital they claim to be based at? If they give a contact number or contact details, do these actually work? These methods are not foolproof: any forms of communication can be tampered with, and identities can be stolen.

If it’s a review or blog you’re relying on, there are a growing number of giveaway clues and online solutions which may help you separate the “real” from the “fake” in years to come.

Researchers at Cornell University have developed a sophisticated algorithm that can tell fake reviews from real ones. It turns out that fake hotel reviews, for instance, are much more likely to focus on who the person was with (using phrases like “my husband and I”) more likely to use pronounce “I” and “me; and less likely to mention the name of the hotel. At the University of Illinois a computer program is being developed to track a reviewer’s internet protocol address so as to determine what else he or she has been reviewing, how often they generate reviews, and whether they follow a particular pattern of praise.

As the power of online fakery grows, a counter-market in this kind of detection software will surely develop. But until such technologies are mainstream, there are some low-tech questions you can ask yourself. Are there numerous reviews written in a similar voice, using similar words and phrases? Does the language being used in a review or blog sound like a real person, or more like an ad? And what is this purported reviewer’s or blogger’s or tweeter’s name? is it a real name or a random jumble of letters?

All of these are potential red flags signaling that you are in what may well be a treacherous landscape. They tell us that we need to do more work, spend a bit of time being an online detective, before acting on what we read.

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING…MATH LITERATE

Being number literate is essential for understanding the modern world and making the right choices. It’s essential for smart decision-making.

We cannot avoid graphs and charts, numbers and statistics, polls and surveys – whether we’re a chief executive, a junior manager, a doctor, a journalist, a marketer, a lawyer or a stay-at-home mother.

Decisions ranging from whether to wear a helmet when riding a bike, which financial adviser to hire to help ensure a comfortable retirement, who to vote for, or how to interpret medical test results are all predicated on an understanding of probabilities, polls, stats, and studies.

This means that, we need to get much better at deciphering what the numbers are telling us if we want to avoid being manipulated by the information we receive, or making decisions from a position of only a partial understanding.

We have to become much more savvy, much more up-to-date and well-acquainted with all kinds of mathematical challenges, if we are to be empowered decision-makers.

MONITOR YOUR EMOTIONAL THERMOSTAT

THE THING ABOUT FEAR

Reflect, just for a moment, on past instances of acute stress. We’ve all been there. For some it will be triggered by speaking in public, for others, by rumors of a round of redundancies, or by a full-blown media crisis on their watch. In some cases, it might simply be a spider in the bath.

You have experienced the sensation: heart thumping loud in your ears, sweaty palms, a quickening of the breath and goosebumps prickling down your arms.

Each of these is a sign that your body is on high alert, and preparing you either to fight or to run for your life.

Although the intensity of fear may vary—a spider in the bath is hardly the same as one of your ancestors coming face-to-face with a hungry lion—the chemical chain reaction both events set off hasn’t changed a bit.

What has changed is the kind of frightening and stressful situations modern humans come up against. This mismatch between our fight-or-flight system evolved for and what it now faces can lead to catastrophic decision-making.

The trouble is that for many of us the familiar patterns we default to when under severe stress can be caricatured and prejudiced.

Take doctors. Studies show that in situations of acute stress, such as when responding to an emergency call from a patient with chest pain, doctors tend to evaluate Hispanic or black patients as much less likely to have coronary heart disease than Caucasian ones, and are less likely to refer non-Caucasians to see a heart specialist.

It’s not just acutely stressful situations that can skew our decision-making. The day-to-day, ongoing stress that many of us increasingly feel nowadays can be just as influential. Chronic stress can lead to excessive tunnel vision, which is bad news for decision-making. It can also generate all-consuming self-doubt, and inordinate focus on negative thoughts – both of which can also powerfully impair our decision-making performance in both our professional and personal lives.

FEELINGS AND DECISIONS—WHY BEING HAPPY MAY BE A BAD THING

When it comes to distorting our decisions, stress is not the only culprit. Our moods and emotions more generally have this effect on us too. People leave bigger tips – regardless of the level of service – when the weather is sunny, because they’re in a better mood. When a national football team loses in a country mad about the sport, its stock market typically plungers because investors are feeling gloomy. While the extent to which you trust a colleague, it turns out, depends less on their qualities and more on how it is you are currently feeling.

Our feelings, then, can distort our ability to make good decisions, but at the same time we actually need our emotions to help us make choices. Indeed, without emotions, we wouldn’t be able to make any decisions at all.

WHAT TO DO

We are not robotic decision-makers, dispassionately weighing various bits of information and coming to our choices in a purely logical fashion. Our pasts could steer us in particular directions, as could colors, words, touch and smell. We have seen that how we feel and our physical state have a profound impact on our decision-making.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. Often our emotional steers help us from making disastrous decisions – fear can, after all, be a very useful warning signal, as our hunter-gatherer ancestors knew all too well.

Yet, unchecked, unacknowledged and uncontemplated, our emotions can lead us to make pretty bad choices. Especially as, in a world as complex as ours, our adaptive evolutionary feelings will not always prove either appropriate or intelligent.

The good news is that there are positive measures we can take to ensure that our emotions and animal impulses do not rule us. We can remove ourselves from extraneous stressors, close our doors, unplug, delegate non-essential matters to someone else. We can pare down the number of decisions we have to make, so as not to take more than what we can handle.

EMBRACE DISSENT AND ENCOURAGE DIFFERENCE

Why are we prone to being so easily influenced?

There are many potential explanations. Clearly at the core is a desire to fit in and be liked: social or peer pressure in some shape or form.

Dr. Gregory Burns, is a neuro-economist by trade, with joint professorship in Psychiatry and Economics at Emory University. He became hot property following the financial crash in 1988, as magazines and TV stations like ABC, CNN and PBS all sought mavens to explain why traders were behaving the way they were, and causing such havoc. But before media made him famous, Berns sought to understand the brain behavior of a much younger group: teenage music fans.

In 2006, working from his lab, Berns studied the brains of twenty-seven children between the age of twelve and seventeen while they were played sixty tracks in three of their favorite genres by unsigned musical artists found on Myspace. Lying down on an fMRI scanner, and then asked to rate it on a star system of from one to five. They were then played the same fifteen-second clip again. In two-thirds of these replays, participants were flashed a “popularity” star rating for the song they were listening to. With this popularity score in front of them, they were then asked to rate the song. For the other one-third of occasions, no popularity rating was shown.

The results were pretty illuminating. When no popularity rating was shown, the kids only switched their choices 11.6 percent of the time when asked to re-rate the song. But once exposed to others’ ratings, that figure almost doubled: 21.9 percent of the original scores were now changed. And in what way? In 79.9 percent of the cases, in the direction of the popularity score.

THE CASE FOR DISSENT

So, we copy, conform with and surround ourselves with people like us—that much is clear. But how does this affect our decision-making?

Badly.

Although several heads can be better than one if we’re trying to solve challenging problems, making forecasts or facing complex decisions, all those extra minds will not be of any real use if they are just replicas of our own.

If the views they espouse, the ideas they bring to the table and the approaches they suggest are simply echoes of what we already believe, know and do, then they take us no further forward. They offer us nothing new in the way of challenge. They tell us little about whether we’ve got our plans right or wrong. Indeed, the more “clubby” the environment, the less willing people will be to voice dissenting views – often the very views we need to hear in order to improve our decision-making.

History is littered with bad decisions and erroneous predictions made because of excessive conformity and insufficient divergence. Excessive group-think is recognized to have underpinned President Kennedy’s disastrous authorization of a CIA-backed landing at Cuba’s Bay of Pigs.

Think back to the billions spent by corporations preparing for Y2K – the bug that was expected to bring down computer networks worldwide on the stroke of midnight at the beginning of the new millennium. As we now know, nothing significant happened beyond a feeling that we’d all been expensively duped and acted like a global flock of sheep that failed to challenge what quickly became a kind of media group-think.

This means that if we are to make smarter decisions, we need to actively take steps to bring dissenters and challengers into our inner circle, our network, our management team.

CONCLUSION

TAKE TIME TO CONTROL

We won’t always have happy-ever-after endings to our decisions, however carefully and thoughtfully we approach them. The ever more complex and unpredictable nature of twenty-first century life means that there will always be some curveballs thrown our way.

We are the creative force of our life, and through our own decisions rather than our conditions. If we carefully learn to do certain things, we can accomplish those goals.

—Stephen Covey

But the author wanted to research and write this book so that she and her readers would have a much better chance of getting those high-stakes decisions in our personal and professional lives right. Decisions such as which job to take and which to walk away from, which investments to take and which acquisitions to champion, whose advice to take and whose to disregard, which medical treatment to agree to for ourselves or our loved ones.

Life is a series of big decisions. But if we take control of the decision-making process, eyes wide open and brains switched on, we can at least stack the odds of making the right calls firmly in our favor.

The onus is on us – we must make this an age of self-empowerment.

An age in which we take control, in which we get vastly better at understanding the world around us and become first-class decision-makers in our own right.

TIME TO FREE UP HEAD SPACE

All this takes time and effort.

Those of us with ever-expanding to-do lists, committing to this may feel like an overwhelming and impossible task. The author acknowledge the increasing pressure we often feel under nowadays to respond instantly, and to make our decisions on the hoof. Yet it’s vital that we free up head space and thinking time when we have important decisions to make.

It’s only by allowing ourselves that beat, that pause, that we can ensure that our brains are sufficiently switched on.

TIME TO KNOW OURSELVES BETTER

We will also need to commit to greater introspection. Acknowledge the need at times to quiet our own egos – for not only must we be more willing to challenge others, we also have to be willing to let others challenge us. Time and time again we’ve seen that many of our best ideas, solutions, and choices arise not from those “kumbaya” moments, when we all clap each other on the back in self-congratulation, but instead from those moments of discord and discomfort, when someone’s shaken us out of our complacency or exposed our own tunnel vision to us. We need to acknowledge our own thinking traps and our own biases, however smart we may think we are.

We need to recognize that this is a time in which the truth is increasingly determined by market forces. In which those who seek to influence us for their own gain are becoming ever more sophisticated when it comes to triggering our most primitive reactions and urges.

And we really must get better at monitoring our basic physical needs – for as we know, a lack of sleep or food can seriously imperil our decision-making.

CLOSING WORDS

Empower yourself.

Take control.

Be a rebel.

Encourage dissent.

Know yourself better.

Allow yourself time and space to think.

Understand the world around you.

Accept uncertainty.

Give yourself permission to change tack.

Keep your eyes wide open and your brains switched on.

All of these are possible, and are within your grasp.

They will help make you a better decision-maker.

Good luck on your journey!

/// end