By Manuel “Bobby” Orig, Consultant, Apo Agua

HIDDEN POTENTIAL

The Science of Achieving Greater Things

By Adam Grant

Hidden Potential illuminates how we can elevate ourselves and others to unexpected heights.

We live in a world obsessed with talent. We celebrate gifted students in school, natural athletes in sports, and child prodigies in music. But admiring people who start out with innate advantages leads us to overlook the distance we ourselves can travel. We underestimate the range of skills that we can learn and how good we can become. We can all improve at improving. And when opportunity doesn’t knock, there are ways to build a door.

Hidden Potential offers a new framework for raising aspirations and exceeding expectations. Adam Grant weaves together groundbreaking evidence, surprising insights, and vivid storytelling that takes us from the classroom to the boardroom, the playground to the Olympics, and the underground to outer space. He shows that progress depends less on how hard you work than how well you learn. Growth is not about the genius you possess – it’s about the character you develop. Grant explores how to build the character skills and motivational structures to realize our own potential, and how to design systems that create opportunities for those who have been underrated and overlooked.

Many writers have chronicled the habits of superstars who accomplish great things. This book reveals how anyone can rise to achieve greater things. The true measure of your potential is not the height of the peak you’ve reached, but how far you’ve climbed to get there.

Praise for the book:

I read Hidden Potential in one sitting, loved it, and have been thinking about it ever since. Which is the highest praise I can give a book. This is Adam Grant’s finest work – it will inspire you to bigger dreams.

—MALCOLM GLADWELL, Author of Outliers

This brilliant book will shatter your assumptions about what it takes to improve and succeed. I wish I could go back in time and gift it to my younger self. It would would’ve helped me find a more joyful path to progress.

—SERENA WILLIAMS, 23-time Grand Slam Singles Tennis Champion

About the author:

Adam Grant has been recognized as Wharton School University of Pennsylvania top-rated professor for seven straight years. As an organizational psychologist, he is a leading expert on how we can find motivation and meaning, and live more generous and creative lives. He has been recognized as one of the world’s 10 most influential management thinkers. Grant is the #1 bestselling author of 5 books that have sold millions of copies and been translated into 35 languages: Think Again, Give and Take, Option B, and Power Moves. His books have been named among the year’s best by Amazon, Apple, the Financial Times, and the Wall Street Journal.

Grant received his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan and his B.A. from Harvard University. He has been recognized as one of the world’s most-cited, most prolific, and most influential researchers in business and economics.

INTRODUCTION

The true measure of your potential is not the height of the peak you’ve reached. It’s how far you’ve climbed to get there.

—Adam Grant

Everyone has hidden potential. This book is about how we unlock it. There’s a widely held belief that greatness is mostly born – not made. That leads us to celebrate gifted students in school, natural athletes in sports, and child prodigies in music. But you don’t have to be a wunderkind to accomplish great things. The author’s goal is to see how we can all rise to achieve greater things.

As an organizational psychologist, he spent much of his career studying the forces that fuel our progress. What he learned might challenge some of your fundamental assumptions about the potential in each of us.

In a landmark study, psychologists set out to investigate the roots of exceptional talent among musicians, artists, scientists, and athletes. They conducted extensive interviews with 120 Guggenheim-winning sculptors, internationally acclaimed concert pianists, prizewinning mathematicians, pathbreaking neurology researchers, Olympic swimmers, and world-class tennis players – and with their parents, teachers, and coaches. They were stunned to discover that only a handful of these high achievers had been child prodigies.

Recent evidence underscores the importance of conditions for learning. To master a new concept in math, science, or a foreign language, it typically takes seven or eight practice sessions. That number of reps held across thousands of students, from elementary school all the way through college.

When we assess potential, we make the cardinal error of focusing on starting points – the abilities that are immediately visible. In a world obsessed with innate talent, we assume the people with the most promise are the ones who stand out right away. But high achievers vary dramatically in their initial aptitudes. If we judge people only by what they can do on day one, their potential remains hidden.

You can’t tell where people will land from where they begin. With the right opportunity and motivation to learn, anyone can build the skills to achieve greater things. Potential is not a matter of where you start, but how far you travel. We need to focus less on starting points and more on distance travelled.

For every Mozart who makes a big splash early, there are multiple Bachs who ascend slowly and bloom late. They’re not born with invisible powers; most of their gifts are homegrown or homemade. People who make major strides are rarely freaks of nature. They’re usually freaks of nurture.

Neglecting the impact of nurture has dire consequences. It leads us to underestimate the amount of ground that can be gained and the range of talents that can be learned. As a result, we limit ourselves and the people around us. We cling to our narrow comfort zones and miss out on broader opportunities. We deprive the world of greater things.

Stretching beyond our strengths is how we reach our potential and perform at our peak. But progress is not merely a means to the end of excellence. Getting better is a worthy accomplishment in and of itself. The author want to explain how we can improve at improving.

This book is not about ambition. It’s about aspiration. As the philosopher Agnes Callard highlights, ambition is the outcome of what you attain. Aspiration is the person you hope to become. The question is not how much money you earn, how many fancy titles you land, or how many awards you accumulate. Those status symbols are poor proxies for progress. What counts is not how hard you work but how much you grow. And growth requires much more than a mindset – it begins with a set of skills that we normally overlook.

ACTING OUT OF CHARACTER

When Aristotle wrote about qualities like being disciplined and prosocial, he called them virtues of character. He described character as a set of principles that people acquired and enacted through the sheer force of will. The author used to see character that way too – he thought it was a matter of committing to a clear moral code. But his job is to test and refine the kinds of ideas that philosophers love to debate. Over the past two decades, the evidence he gathered has challenged him to rethink that view. He now see character less as a matter of will, and more as a set of skills.

Character is more than just having principles. It’s a learned capacity to live by your principles. Character skills equip a chronic procrastinator to meet a deadline for someone who matters to them and a shy introvert to find the courage to speak out against an injustice.

IF YOU BUILD IT, THEY WILL CLIMB

When people talk about nurture, they’re typically referring to the ongoing investment that parents and teachers make in developing and supporting children and students. But helping them reach their full potential requires something different. It’s a more focused, more transient form of support that prepares them to direct their own learning and growth. Psychologists call it scaffolding.

In construction, scaffolding is a temporary structure that enables work crews to scale heights beyond their reach. Once the construction is complete, the support is removed. From that point forward, the building stands on its own.

In learning, scaffolding serves a similar purpose. A teacher or coach offers initial instruction and then removes the support. The goal is to shift the responsibility to you so you can develop your own independent approach to learning.

SKILLS OF CHARACTER

Getting Better at Getting Better

In the late 1800s, the founding father of psychology made a bold claim. “By the age of thirty,” William James wrote, “character has set like plaster and will never soften again.” Kids could develop character, but adults were out of luck.

Recently, a team of social scientists launched an experiment to test that hypothesis. They recruited 1,500 entrepreneurs in West Africa – a mix of women and men in their 30s, 40s, and 50s – who were running small startups in manufacturing, service, and commerce. They randomly assigned the founders to one of three groups. One was a controlled group: they went about their business as usual. The other were training groups: they spent a week learning new concepts, analyzing them in case studies of other entrepreneurs, and applying them to their own startups through role-play and reflection exercises. What differed was whether the training focused on cognitive skills or character skills.

In cognitive skills training, the founders took an accredited business course created by the International Finance Corporation. They studied finance, accounting, HR, marketing and pricing, and practiced using what they learned to solve challenges and seize opportunities.

In character skills training, the founders attended a class designed by psychologists to teach personal initiative. They studied proactivity, discipline, and determination, and practiced putting those qualities into action.

Character skills training had a dramatic impact. After founders had spent merely five days working on these skills, their firms’ profits grew by an average of 30 percent over the next two years. That was nearly triple the benefits of training in cognitive skills. Finance and marketing knowledge might have equipped founders to capitalize on opportunities, but studying proactivity and discipline enabled them to generate opportunities. They learned to anticipate market changes rather than react to them. They developed more creative ideas and introduced more new products. When they encountered financial obstacles, instead of giving up, they were more resilient and resourceful in seeking loans.

Along with demonstrating that character skills can propel us to achieve greater things, this evidence reveals that it’s never too late to build them.

Character is often confused with personality, but they’re not the same. Personality is your predisposition – your basic instincts for how to think, feel, and act. Character is your capacity to prioritize your values over your instincts.

Knowing your principles doesn’t necessarily mean you know how to practice them, particularly under stress or pressure. It’s easy to be proactive and determined when things are going well. The true test of character is whether you can manage to stand by those values when the deck is stacked against you. If personality is how you respond on a typical day, character is how you show up on a hard day.

Personality is not your destiny – it’s your tendency. Character skills enable you to transcend that tendency to be true to your principles. It’s not about the traits you have – it’s what you decide to do with them. Wherever you are today, there’s no reason why you can’t grow your character skills starting now.

MINING FOR GOLD

Unearthing Collective Intelligence in Teams

The second they saw the avalanche start raining down from above, a group of men raced for cover. Some of their colleagues couldn’t see it yet, but the sound was unmistakable: an ominous low rumble that intensified into an earsplitting crack. A gust lifted one of them off the ground and sent another sailing through the air. They picked themselves up and started making their escape on foot.

Struggling to see or hear with rocks flying everywhere, they feared they wouldn’t make it. Then they spotted a pickup truck barreling down the road. They jumped aboard and held on for dear life as the truck crashed twice. When they reached the bottom of the road, they were finally safe from the avalanche. But they weren’t really safe. They were trapped 2,300 feet underground.

It was August 2010 and a gold and copper mine in the Chilean desert had just collapsed. A massive chunk of rock as tall as a 45-storey building had broken free from the mountain above. The only entrance was blocked by more than 700,000 tons of rock. There were 33 men sealed inside. They were given less than 1 percent chance of making it out alive.

Yet 69 days later, they were all reunited with their families. It was a monumental and miraculous rescue effort – this was the longest humans had ever survived after being trapped underground. As the author watched the rescue capsule bring the first miner to safety, his eyes welled up with tears of joy and relief. At the time, most of the coverage focused on how the miners did it. It wasn’t until years later that the author realized how much the rescue team could teach us about how groups travel great distances together.

At the outset of the rescue mission, no one knew if the miners were even still alive. And there was no easy way to determine that. The maps of the mine were unfinished and outdated, leaving the rescue team “drilling blind.” It was like searching for a needle in a haystack twice the height of the Eiffel Tower. They had to estimate the location of the miners and the curved path of a massive drill. If they were off by just a few degrees at the surface, they could miss the mark by hundreds of feet in the mine.

On day seventeen, the rescue team found a glimmer of hope. As one of the drills finally reached the area where they expected the safety refuge to be, they tried to send a signal to the miners by pounding the drill with a hammer. It sounded like something was banging back. Sure enough, when they spun the drill in reverse to bring it to the surface, they found the end covered in orange paint, with pieces of paper attached to it. The trapped miners had written notes announcing that they had all survived. Just in case the notes got shredded or detached, they’d spray-painted the drill as proof of life.

By that point, however, the miners were in dire straits. Their supplies had dwindled. They were down to contaminated water and a single bite of tuna fish every three days. The rescue team was able to buy them some time by drilling tiny holes that wouldn’t risk another collapse of the mine – one for food and water, another for oxygen and electricity. But now they had to figure out how to drill a hole wide enough for humans … half a mile deep … without burying the miners alive. A rescue like this had never been attempted before, let alone successfully.

When we face complex and pressing problems, we know we can’t solve them alone. We assume our most important decision is to assemble the most knowledgeable people. Once we’ve found the right experts, we put our future in their hands.

But that’s not what the leaders of the Chilean mine rescue did. Instead of merely relying on an exclusive group of established experts, they built a system to bring a broader and deeper pool of ideas and intelligence to the surface. When they made their first voice contact with the miners, it was thanks to a $10 innovation from a small-time entrepreneur. The eventual rescue was made possible by a series of suggestions from a 24-year-old engineer who wasn’t even part of the core team.

Maximizing group intelligence is about more than enlisting individual experts – and it involves more than merely bringing people together to solve a problem. Unlocking the hidden potential in groups requires leadership practices, team processes, and systems that harness the capabilities and contributions of all their members. The best teams aren’t the ones with the best thinkers. They’re the teams that unearth and use the best thinking of everyone.

ANY TEAM WON’T DO

The author started wondering how groups come together to achieve greater things when he was a junior in college. It happened in the class that hooked him on organizational psychology. Rumor had it that the professor taught it so early in the morning in the hopes of attracting only the most motivated students.

The professor’s name was Richard Hackman, and he was the world’s leading expert on teams. He spent nearly half a century studying teams in every field imaginable – from airline cockpit crews to hospital units to symphony orchestras. He’d found that in most cases, teamwork failed to make the dream work. It was more likely to be a nightmare … as anyone who ever did a group project in school can attest. Most teams were less than the sum of their parts.

Richard spent the next few years working with one of his star proteges, Anita Wooley, to study how to make teams smarter. Eventually, Anita and her collaborators made a breakthrough. They revealed something vital to making teams more than the sum of their parts.

Anita was interested in collective intelligence – a group’s capacity to solve problems together. In a series of pioneering studies, she and her colleagues tackled how well various teams performed on a wide range of analytical and creative tasks. The author expected collective intelligence to depend on how well the task matched the abilities of individuals in the group. He thought that teams of verbal virtuosos would dominate word scrambles, teams of math whizzes would win at geometry problems, and teams of proactive people would have the edge in planning and execution situations. He was wrong.

Surprisingly, certain groups consistently excelled, regardless of the type of task they were doing. No matter what kind of challenge Anita and her colleagues threw at them, they managed to outperform the others. His assumption was that they were lucky to have a bunch of geniuses. But in the data, collective intelligence had little to do with individual IQs. It turned out that the smartest teams weren’t composed of the smartest individuals.

Since these initial studies, scientific interest in collective intelligence has exploded, shedding light on what propels teams to achieve greater things. In a meta-analysis of 22 studies, Anita and her colleagues discovered that collective intelligence depends less on people’s cognitive skills than their prosocial skills. The best team have the most team players – people who excel at collaborating with others.

Being a team player is not about getting along all the time and ensuring everyone’s cooperation. It’s about figuring out the group needs and enlisting everyone’s contribution. Although it’s nice to have a savant or two on the team, they do little good if no one else sees their value and people pursue their own agendas. It’s well documented that a single bad apple can spoil the barrel: when even one individual fails to act prosocially, it’s enough to make a team dumb and dumber.

You can see the bad-apple problem in a study of NBA basketball teams – a setting where players who lack prosocial skills stand out as self-centered and narcissistic. If teams had many narcissists or even one extreme narcissist, they completed fewer assists and won fewer games. They also failed to improve over the season especially if their point guard (the primary passer and play caller) scored high on narcissism.

When they have prosocial skills, team members are able to bring out the best in one another. Collective intelligence rises as team members recognize one another’s strengths, develop strategies for leveraging them, and motivate one another to align their efforts in pursuit of a shared purpose. Unleashing hidden potential is about more than having the best pieces – it’s about having the best glue.

IT’S NOT ALL ABOUT ME

Prosocial skills are the glue that transforms groups into teams. Instead of operating as lone wolves, people become part of a cohesive pack. We normally think about cohesion in terms of interpersonal connection, but team building and bonding exercises are overrated. Yes, icebreakers and ropes courses can breed camaraderie, but meta-analyses suggest that they don’t necessarily improve team performance. What really make a difference is whether people recognize that they need one another to succeed on an important mission. That’s what enables them to bond around a common identity and stick together to achieve their collective goals.

Putting people in a group doesn’t automatically make them a team. Richard showed that the best groups of intelligence analysts gelled into real teams. They were evaluated on a collective outcome. They aligned around a common goal and carved out a unique role for each member. They knew that their results depended on everyone’s input, so they shared their knowledge and coached one another on a regular basis. That made it possible for them to become a big sponge – they were able to absorb, filter, and adapt to information as it emerged and evolved.

MANY BRAINS MAKE LIGHT WORK

When we’re confronting a vexing problem, we often gather a group to brainstorm. We’re looking to get the best ideas as quickly as possible. The author love seeing it happen … except for one tiny wrinkle.

In brainstorming meetings, many good ideas are lost – and few are gained. Extensive evidence shows that when we generate ideas together, we fail to maximize collective intelligence. Brainstorming groups fall so far short of their potential that we get more ideas – and better ideas – if we all work alone. As the humorist Dave Barry quipped, “If you had to identify, in one word, why the human race has not achieved, and never will achieve, its full potential, that word would be: ‘meetings.’”

The problem isn’t meetings themselves – it’s how we run them. Think about the brainstorming sessions you’ve attended. You’ve probably seen people bite their tonques due to ego threat (I don’t want to look stupid), noise (we can’t all talk at once), and conformity (let’s all jump on the boss’s bandwagon). Goodbye diversity of thought, hello groupthink. These challenges are amplified for people who lack power or status: the most junior person in the room, the sole woman of color in a team of bearded white dudes, the introvert drowning in a sea of extraverts.

When groups meet to brainstorm, good ideas are lost. People bite their tongues due to conformity pressure, noise, and ego threat.

A better approach is brainwriting: generate ideas separately, then meet to assess and refine.

Group wisdom begins with individual creativity. pic.twitter.com/02Z3okOfu7

— Adam Grant (@AdamMGrant) August 29, 2022

To unearth the hidden potential in teams, instead of brainstorming, we’re better off shifting to a process called brainwriting. The initial steps are solo. You start by asking everyone to generate ideas separately. Next, you pool them and share them anonymously among the group. To preserve independent judgment, each member evaluates them on their own. Only then does the team come together to select and refine the most promising options. By developing and assessing ideas individually, before choosing and elaborating them, teams can surface and advance possibilities that might not get attention otherwise.

Research by Anita Wooley and her colleagues helps to explain why this method works. They find that another key to collective intelligence is balanced participation. In brainstorming meetings, it’s too easy for participation to become lopsided in favor of the biggest egos, the loudest voices, and the most powerful people. The brainwriting process makes sure all ideas are brought to the table and all voices are brought into the conversation. Sure enough, there’s evidence that brainwriting is especially effective in groups that struggle to achieve collective intelligence.

Collective intelligence begins with individual creativity. But it doesn’t end there. Individuals produce a greater volume and variety of novel ideas when they work alone. That means that they come up with more brilliant ideas than groups – but also more terrible ideas than groups. It takes collective judgment to find the signal in the noise.

In Chile, Andre Sougarret, the leader of the rescue team appointed by Chile’s president, didn’t get the best ideas by gathering his team for long brainstorming sessions. Instead, he and his colleagues established a global brainwriting system to crowdsource search and rescue proposals from a diverse network of contacts.

Hundreds of ideas poured in, and some were far-fetched. One contributor suggested strapping panic buttons to a thousand mice and letting them loose in the mine, hoping the miners would find them. Another had spent two weeks inventing a miniature yellow plastic telephone to send down a hole to the miners. It gave the engineers on-site a much-needed laugh. As usual, brainwriting yielded variance as well as volume.

Thankfully, some of the submissions provided more than entertainment value. An independent mining engineer pitched the idea of transporting food and water via a 3.5-inch tubes. The team adopted his suggestion, and it ended up becoming a lifeline for the miners. Along with providing sustenance, it became their conduit for communicating with the rescuers.

The rescue team sent a high-tech camera down to the miners. For the rest of the time, they could see one another. But the audio didn’t work. The engineers tried a number of solutions, but all of them failed. Finally, they swallowed their pride and called for the tiny yellow phone. After attaching it to a fiber-optic cable, the plastic device became the sole means of speaking with the miners. The solo entrepreneur who built it, Pedro Gallo, talked with the trapped men every day.

LETTING A THOUSAND FLOWERS BLOOM

The most extensive analysis of the collaboration lessons from the rescue team was led by the author’s colleague, Amy Edmonson. She started her career as an engineer, became a disciple of Richard Hackman’s, and is now among the world’s foremost experts on teams. After interviewing many of the key players in the rescue effort, Amy encouraged the author to dig into one story in particular, assuring him it was worth its weight in gold.

One day, a young engineer name Igor Proestakis was on-site delivering drilling equipment when he bumped into the geologists overseeing the drilling. He told them about an idea he had to access the miners faster. It was a bold alternative to plan A: Instead of slowly drilling a new hole, what if they rapidly expanded one of the existing holes? Igor thought they might be able to do it with a tool called a cluster hammer – a special drill designed to smash right through rock.

Igor didn’t expect his suggestion to go anywhere. He was one of the youngest, least experienced engineers at the site. His role was to advise drill operators on how to use his company’s equipment effectively, not to propose new strategies and technologies. But when he mentioned his idea to the geologists, they asked him to share it with Andre Sougarret. Could he have his presentation ready in two hours? You want me to do what? Igor remembers thinking. He didn’t know why anyone would listen to him. “I was just a 24-year-old, giving my opinion.”

Later that day, when Igor presented the idea, Andre didn’t shut him down. He wasn’t looking for an excuse to say no – he was listening carefully for reasons to say yes. “This was probably the most important job of his life,” Igor recalls, “and despite my experience and age, he listened to me, asked questions, gave it a chance.” Andre asked him to put together a pitch for Chile’s mining minister. Soon the idea was approved.

In many organizations, Igor wouldn’t have the chance to pitch his idea in the first place, let alone have it adopted. “In a normal organization, he would never have spoken up,” Amy Edmonson told the author. “But in this setting, the climate had been created where he felt he could – and he did.”

We normally call that a climate for voice and psychological safety. There’s evidence that just a look at by the leader is enough to encourage people who lack status to speak up. But as the author dug into Amy’s research, something caught his eye. The rescue leaders hadn’t just established a climate – they had built an unconventional system for making sure that ideas were carefully considered rather than dismissed. And it’s a system that the author have seen unlock intelligence in all kinds of settings.

BARBARIANS AGAINST THE GATEKEEPERS

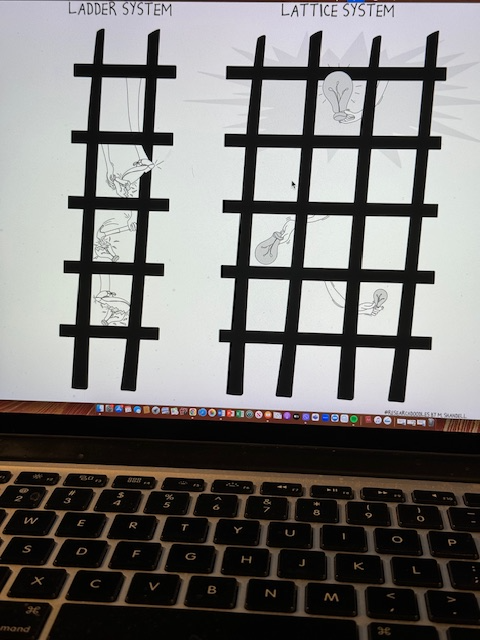

In most workplaces, opportunity exists on a ladder. The person immediately above you is in charge of decisions about your growth. Your direct boss sets your job description, vets your suggestions, and determines your readiness for promotion. If you can’t get your boss to hear you out, your proposal is toast. The system is simple. But it’s also stupid – it gives one individual far too much power to shut creativity down and shut people up. A simple no is enough to kill an idea – or even stall a career.

In many cases, unproven ideas carry too much risk and uncertainty. Managers know that if they bet on a bad idea, it might be a career-limiting move, but if they pass on a good idea, it’s unlikely anyone will ever find out. And even if managers are supportive of an idea, if they perceive leaders above them as opposed to it, they tend to see it as a losing proposition. All it takes is one gatekeeper to close off a new frontier.

That kind of hierarchy is set up to reject ideas with hidden potential. You can see it clearly in the tech world. Xerox programmers pioneered the personal computer but struggled to get managers to commercialize it. An engineer at Kodak invented the first digital camera but couldn’t persuade management to prioritize it.

Organizations can solve this problem with a different kind of hierarchy. A powerful alternative to a corporate ladder is a lattice. A physical lattice is a crisscrossing structure that looks like a checkerboard. In organizations, a lattice is an organizational chart with channels across levels and between teams. Rather than one path of reporting and responsibility from you to the people above you in the hierarchy, a lattice offers multiple paths to the top.

A lattice system isn’t a matrix organization. You’re not stuck with eight different bosses breathing down your neck. You don’t have multiple managers holding you back and shooting you down. The goal is to give you access to multiple leaders who are willing and able to help move you forward and lift you up.

The best example the author has seen of a lattice system is at W.L. Gore, the company known of making waterproof Gore-Tex gloves and jackets. Back in the mid-1990s, a rank-and-file medical device engineer at Gore name David Myers found out that coating the gear cables on his mountain bike with Gore-Tex protected them from grit. It dawned on him that Gore-Tex might also be useful for repelling grit from human hands that leads guitar strings to lose their tone over time.

Even though it wasn’t part of his day job, Dave took the initiative to mock up a prototype. He brought it to some senior people, but they didn’t think it was worth pursuing. They had technical objections. You can’t coat a vibrating string with fluoropolymer – you’ll ruin the sound! They had strategic concerns too. We’re not in the music business – why would we make guitar strings.

In a typical organization, those protests would have been enough to squash the idea. But Gore has a lattice system. Whenever you have an idea, you’re granted the freedom to go up to a range of different senior people. To get your project off the ground, all you need is one leader who’s willing to sponsor it. So Dave kept socializing his idea. Eventually he found a sponsor, Richie Snyder, who connected him with an engineer named John Spencer.

For the next year, Dave and John dedicated part of every work week to their unproved idea. Instead of seeing those kinds of side projects as diverting or disobedient, Gore encouraged them – they give people “dabble time” to tinker. To make headway on the guitar strings, Dave and John didn’t need Richie’s formal approval. They just gave him regular updates as they developed and tested prototypes with thousands of musicians.

A lattice system rejects two unwritten rules that dominate ladder hierarchies: don’t go behind your boss’s back or above your boss’s head. Amy Edmondson’s research suggests that implicit rules stop many people from speaking up and being heard. The purpose of a lattice system is to remove the punishment for going around and above the boss.

At Gore, Dave and John weren’t shy about going above Richie’s head when they needed ideas and support. They took advantage of the leeway to contact anyone at any time.

It took Dave, John, and their makeshift team 18 months to develop and launch the product. Just 15 months later, their Elixir strings became the market leader in strings for acoustic guitars. It’s not every day that an idea hatched in a medical products division makes a dent in the music industry. But it did, thanks to the lattice system.

LIGHT AT THE BOTTOM OF THE TUNNEL

When the author first learned about how Igor Proestakis pitch his plan, he immediately recognized the hallmarks of a lattice system. It was why he was able to bring his idea to the geologists supervising the drilling – and why they took him straight to the top despite his youth and inexperience. But the benefits of the lattice system became even more visible about a month into the rescue initiative.

Plan A of the rescue plan was moving even slower than anticipated. Igor’s plan B was looking better and better. Igor had been right about his cluster hammer proposal: it was smashing swiftly and smoothly through the rock … until it stopped working altogether.

It turned out that they hit a series of iron rods that were in place to reinforce the mine, which shattered the hammer’s drill into pieces. One of those pieces – a hunk of a metal the size of a basketball – was now blocking the hole they were expanding to reach the miners.

The next day, Igor had an idea. He remembered an extraction tool he’d read about in school – an industrial version of an arcade claw machine. My wife Allison, is the master of that machine, but we had no idea it served a purpose higher than winning plush teddy bears. It was exactly the kind of approach they needed. If they could lower a metal jaw and clamp its teeth around the obstructing piece of metal, they could extract it and clear the hole.

When Igor first suggested the claw machine to a few people on-site, they didn’t listen. But due to the lattice system, he knew he had other routes to getting his idea heard. After two days of having his idea ignored at lower levels, Igor managed to get an audience with the Chilean mining minister himself, who give it the green light right away. For the next five days, they tried and failed until it finally captured the broken drill bit, lifted it out, and opened the hole. To everyone relief, plan B was back on track.

Late one evening the following month, a rescue worker went down through that hole in a capsule. Shortly before midnight, the capsule came back up carrying the first miner. And less than 24 hours later, the rescue capsule carried the foremen – the last of the 33 miners – out through the hole.

On This Day in 2010 33 Chilean miners are rescued after being trapped underground for 69 days in the San Jose mine https://t.co/qBtDU9BDau pic.twitter.com/8VNgkWydAt

— The Daily Telegraph (@dailytelegraph) October 13, 2016

Igor’s claw idea helped save 33 lives. There’s no question that we should applaud the creative, heroic efforts from him and so many others. But let’s not forget the unsung heroes of this story: the leadership practices, team processes, and systems of opportunity that make it possible for people to speak up and be heard.

If we listen only to the smartest person in the room, we miss out on discovering the smarts that the rest of the team has to offer. Our greatest potential isn’t always hidden inside us, and sometimes it comes from outside our team altogether.

DIAMONDS IN THE ROUGH

Success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles … overcome while trying to succeed.

—Booker T. Washington

On a historic evening in 1972, ten year old Jose Hernandez kneeled in front of an old black-and-white television. As the fuzzy image on the screen became clearer, Jose watched the last Apollo astronaut bound across the surface of the moon.

Jose was mesmerized by the moonwalk, but he yearned for an even better view. He unglued his eyes from the screen, raced outside to look at the moon, and ran back in time to see one of the astronauts take the final giant leap. Jose hoped that one day, he could etch his own footsteps alongside theirs in the lunar dirt.

Many kids go through an astronaut phase, but Jose was committed to making his dream a reality. Since his strongest subjects were math and science, he decided engineering would be his ride to space. Over the next two decades, he earned a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering and landed a job as an engineer at a federal research facility. He wanted to make his application as strong as possible for NASA.

In 1989, Jose was ready to throw his hat in the ring. He carefully filled out 47 sections of the astronaut application, enclosed his resume and transcripts, and shipped his packet off to Houston. Soon he was checking his mailbox daily, eagerly awaiting an envelope from NASA. After ten long months, it finally arrived. He ripped it open and read the letter from the head of the astronaut selection office. Not selected.

Jose wasn’t fazed. His aspirations were high, but his expectations were modest – he knew the odds were long. He took the initiative to call NASA for feedback, and followed up with a letter asking how he could improve.

I would like to increase my chances during the selection process in my application package. I would therefore deeply appreciate any feedback you can provide regarding the status of my application.

A special thanks for taking time off your schedule to fulfill one of what must be thousands of requests.

NASA got back to him with disappointing news. Since he hadn’t made it past the initial screening, they didn’t have notes or advice for him to absorb. Undeterred, he applied again … and was rejected again.

Jose didn’t give up hope. He kept putting himself back in the ring – revisiting his resume, highlighting his strengths, updating his references as he reapplied – only to be met with rejection after rejection. He couldn’t even get his foot in the door for an interview.

In 1996, the last rejection broke his spirit. Jose had the sinking feeling that he would never be enough for NASA.

In life, there are a few things more consequential than the judgments people make of our potential. When colleges evaluate students for admission and employers interview applicants for jobs, they’re making forecasts about future success. These predictions can become gateways to opportunity. Whether the door swings open or slums shut hands in the balance of their assessments.

What Jose didn’t know was that none of his applications even registered a blip on NASA’s radar. They were looking for people with operational experience making decisions in high-stress environments. They expected to see noteworthy accomplishments by engineers. They took notice of applicants who graduated at the top of their class. NASA was focused on finding people who had already achieved great things, and by their standards, that wasn’t Jose. But what NASA’s process failed to capture – and so many organizations do – was a candidate’s potential for greater things.

NASA missed the markers of Jose’s potential because their selection process wasn’t designed to detect them. They had information about work experience and past performance, not life experience and background. They didn’t know that Jose was raised in a family of migrant farmworkers. They didn’t know that he had traveled a great distance just to make it to college and become an engineer. That lack of accomplishments in his early applications seemed to reveal the absence of ability, but it actually indicated the presence of adversity.

It’s a mistake to judge people solely by the heights they’ve reached. By favoring applicants who have already excelled, selections systems underestimate and overlook candidates who are capable of greater things. When we confuse past performance for future potential, we miss out on people whose achievements have involved overcoming major obstacles. We need to consider how steep their slope was, how far they have climbed, and how they’ve grown along the way. The test of a diamond in the rough is not whether it shines from the start, but how it responds to heat or pressure.

UNCUT GEMS

When the author wanted to find out how to identify hidden potential, he knew NASA was an ideal organization to study. The stakes are high: picking the wrong astronaut could jeopardize a mission and cost crew their lives. That left the agency much more concerned about false positives (accepting bad candidates) than false negatives (rejecting good ones).

To understand why we miss potential and how we can spot it, he reached out to Duane Ross. Duane led astronaut selection at NASA for four decades, signing the rejection letters personally by hand – including each of Jose’s. He wanted to learn about the process of sifting through the dreams of thousands of applicants to put the future of space exploration in the hands of a select few.

Duane and his colleague, Teresa Gomez, were hunting for the rare candidates with the right stuff. With between 2,400 and 3,100 applications for only 11 to 35 spots, they had to quickly size up who had potential and who didn’t. From what they could see, Jose Hernandez didn’t have it.

NASA had no idea that Jose was raised in poverty by undocumented immigrants. To make ends meet, the entire family took a long road trip from central Mexico to Northern California each winter. They stopped at farms along the way to pick everything from strawberries and grapes to tomatoes and cucumbers. Come fall, they headed back down to Mexico for a few months and then started the routine again. The journey forced Jose to miss several months of the year in three different districts. After Jose started second grade, his father began cobbling together day jobs so they could stay in one place, but Jose still had to work weekends in the fields to help support his family. That left him with limited time for homework, and he couldn’t rely on his parents for assistance – they only had third-grade educations.

That history was invisible to NASA. In their search for the right stuff, they didn’t have access to the right stuff. “What should figure out into the process is how hard it was for them to get there,” Duane Ross told the author, having retired after half a century at NASA.

For the initial screen, the federally regulated application process focused on work experience, education, special skills, and honors and awards. The form didn’t ask for unconventional skills like picking grapes. It didn’t signal that gaining a command of the English language would qualify as an honor. The system wasn’t designed to identify and weigh the adversity candidates had overcome.

QUANTIFYING THE UNQUANTIFIABLE

We all know that performance depends on more than ability – it’s also a function of degree of difficulty. How capable you appear to be is often a reflection of how hard your task is.

Yet when we judge potential, we often focus on execution and ignore degree of difficulty. We inadvertently favor candidates who aced easy tasks and dismiss those who passed taxing trials. We don’t see the skills they’ve developed to overcome obstacles – especially the skills that don’t show up on a resume.

Any great achievement is preceded by many difficulties and many lessons; great achievements are not possible without them.

—Bryan Tracy

The goal for measuring degree of difficulty at the individual level isn’t to advantage people who face adversity. It’s to make sure we don’t disadvantage people for navigating adversity. Ultimately, the key indicator of potential isn’t the severity of adversity people encounter – it’s how they react to it. That’s what a better selection system would assess.

MAKING THE INVISIBLE VISIBLE

Too often, our selection systems fail to weigh achievements in the context of degree of difficulty. Research shows that when students apply to graduate school, admissions officers pay surprisingly little attention to the difficulty of their courses and majors. Acing easy classes might give you higher odds of acceptance than doing reasonably well in hard classes.

Selection systems need to put performance in context. It’s like having wrestlers compete in their own weight class. A promising approach is to create metrics that objectively compare students to their peer group.

Displaying the difficulty of the task is only one way of contextualizing performance. We can also adjust for difficulty outside the classroom by comparing students to peers in similar circumstances. Some schools have taken the promising step of expanding transcripts to show students’ grades relative to their neighborhood. Experiments show that this can help admissions officers spot potential in lower-income students without reducing their enthusiasm about students from families with greater means. The author asked Duane Ross about this idea, and he told him that if this kind of information had appeared on Jose’s application, NASA would have given him a closer look.

To afford tuition, Jose worked the graveyard shift at a fruit and vegetable cannery, arriving at 10 p.m. and finishing at 6 a.m. It was a strain to stay alert in class, let alone master the material. When the fruit season ended, he worked nights and weekends as a restaurant busboy. Between demanding classes and a grueling schedule, he finished his first semester with a C average.

The first semester was a particularly bumpy period for Jose. Things improved as he found work with more reasonable hours, established a more sustainable routine, and took the initiative to seek tutoring to fill the gaps in his knowledge. With each semester, his grades climbed. He went on to earn many A’s and graduate with cum laude honors. He won a scholarship at the University of California.

A WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY

Since NASA invited candidates to update their applications every year, Jose got an annual do-over. By 1996, after a string of rejections, he was on the verge of quitting when his wife, Adela, encouraged him not to throw away his dream. “Let NASA be the one to disqualify you,” she urged. “Don’t disqualify yourself.”

Jose realized there was more he could do to qualify himself: he would “become a sponge.” He learned that most astronauts were pilots and scuba divers, so he took a year to earn his pilot’s license and spent another year driving to scuba training every weekend until he got his basic, advanced, and master certifications. And when his federal lab presented him with an unconventional opportunity to work on curtailing nuclear proliferation in Siberia, Jose took it on one condition: he would get to learn to speak Russian as part of the deal. He hoped it would help him stand out in NASA’s next cycle.

After a number of years working as a NASA engineer, in 2004, Jose heard his phone ring. The voice on the other end of the line asked if he was replaceable. Jose said he was happy to train someone to take his place. “Good,” the manager said. “How would you like to come to work for the astronaut’s office?”

After 15 years of applying, Jose was selected to go to space. “The second I heard the good news,” he recalls, “my whole body went numb.” He raced home to break the news to his wife, children, and parents, who celebrated by hugging and dancing.

"A Million Miles Away" is the true story of @NASA Astronaut José Hernández and his wife who overcame exceptional challenges to fulfill his dream to fly in space. This #HHM23, we salute those who have reached for the stars and shown that no dream is too far away.… pic.twitter.com/FvyAV4ARSX

— Bill Nelson (@SenBillNelson) September 19, 2023

In August 2009, a few weeks after turning 47, Jose stepped into the space shuttle. He sat down, buckled in, and braced himself for takeoff. Just before midnight, he heard the countdown and watched the engines light up. Eight and a half minutes after blasting into the sky, the engine shut off, and Jose couldn’t believe his eyes. To convince himself it was real, he tossed a piece of equipment up. Watching it hover, he marveled, “I guess we are in space.”

Jose had gone from picking strawberries in the fields to floating among the stars. Over the course of two weeks in space, he flew over five million miles. It was a short hop compared to the distance he had traveled for the chance to wear a space suit.

As exciting as it is to see a candidate like Jose succeed, it isn’t enough. His success shows us what we’re missing in so many others. He had to break the mold to make it through a broken system. He’s the exception, but he should be the rule.

Every diamond has the ability to shine when there is someone who recognizes its good faces and inhibit its flaws.

—Wes Fesler

When we evaluate people, there’s nothing more rewarding than finding a diamond in the rough. Our job isn’t to apply the pressure that brings out their brilliance. It’s to make sure we don’t overlook those who have already faced that pressure – and recognize their potential to shine.

///end

If you have any comments on our book digest series, please drop us a note aboitiz.eyes@aboitiz.com