By Manuel “Bobby” M. Orig, Director, Apo Agua

A summary of Moments Of Impact: How To Design Strategic Conversations That Accelerate Change by Chris Ertel & Lisa Kay Solomon

This summary is rather long because I covered the key areas that will enable you readers to acquire a good grasp of the power of strategic conversations to resolve adaptive challenges.

I also wanted you to become familiar with the framework, process, and language of designing strategic conversations so that you will have an intuitive feel of how these ideas are put into action.

IN OUR FAST-CHANGING WORLD, leaders are increasingly confronted by messy, multifaceted challenges that require collaboration to resolve. But the standard methods for tackling these challenges – meetings packed with data-drenched presentations or brainstorming sessions that circle back to nowhere – just don’t deliver.

Great strategic conversations generate breakthrough insights by combining the best ideas of people with different backgrounds and perspectives. In this book, two experts “crack the code” on what it takes to design creative, collaborative problem-solving sessions that soar rather than sink.

Drawing on decades of experience as innovations strategists – and supported by cutting-edge social science research, dozens of real-life examples, and interviews with well over 100 thought leaders, executives, and fellow practitioners – they unveil a simple, creative process that leaders and their teams can use to unlock solutions to their most vexing issues.

Praise from Daniel H. Pink, author of To Sell Is Human and Drive

They say insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result. I say that’s also a pretty good definition of the typical business meeting. If you’d like to short circuit the meeting loop and energize your team’s ability to solve real problems and create new visions, then Moments Of Impact is the book you need.

About the authors

Chris Ertel has been designing strategic conversations for seventeen years as an adviser to senior executives of Fortune 500 companies, government agencies, and large non-profits. He is a PhD-trained social scientist.

Lisa Kay Solomon teaches innovation at the MBA in Design Strategy Program at San Francisco’s California College of the Arts and helps executive teams develop the vision, tools, and skills to design better futures.

Introduction: The most important leadership skill they don’t teach at Harvard Business School (or anywhere else)

The call came eight days before the meeting. The caller, Bruce, was anxious. A senior executive at an international development agency, Bruce was about to host one of the biggest meetings of his career. Forty top economic-development experts from around the world were coming to Jakarta – on his invitation – to strategize the future of Asia. As the date approached, Bruce was petrified that the two-day session might flop.

The authors asked Bruce a few questions:

- What’s the purpose of the meeting?

- What are the desired outcomes?

Bruce answered: “We just want people to come and talk, so they can learn from one another. After all, they are the experts.”

- What important points do your experts agree on?

- Where are they at loggerheads?

Bruce: “We figured we’d sort that out in the room. We haven’t had time to talk with everyone in advance.”

- How will you set up the issues?

Bruce: “We’ve got a list of eight priority topics on the agenda. We figured we’d work through them one at a time with the group.”

- What kind of overall experience are you hoping participants will have?

Bruce: “What do you mean by that exactly?”

Designing Strategic Conversations: A Craft

Bruce is an accomplished professional with top-notch education and years of experience running meetings and events. Yet at no point in his career did he learn how to design a gathering like the one he was about to host – a creative, collaborative problem-solving session tackling a messy, open-ended challenge. That is a strategic conversation.

If you are a manager or a leader in your organization today, you have no doubt been to or organized at least a few strategic conversations. At some point, virtually all leaders – at all levels, across all organizations – convene them to address their most vexing challenges. At these critical moments, everyone will be looking to you – not for all the answers, but to help them unearth answers together.

Odds are, you have some ideas on how to set up a strategic conversation – but less than total confidence in how to get great results. Most leaders approach strategic conversations with a degree of anxiety because it’s a skill they were never taught. No major business school or executive education program includes a course on how to design them.

Think about it. We go to great lengths and expense to bring together our best talent, with different skills and backgrounds, to tackle our biggest challenges. Yet we have precious little guidance on how to do this well – either as participants or as leaders.

Because we pay little attention to this skill, every day an otherwise capable leader is hosting a strategy retreat without a clear purpose. Or a strategic planning session packed with presentations that lay out one fact after another without illuminating the choices at hand. Or a feel-good off-site where participants are asked to give their “inputs” though it’s obvious the leaders have already made up their minds. Or a freewheeling brainstorming session “where every idea is good.”

Lots of strategic conversations turn out “okay” – neither home runs nor disasters. But okay strategic conversations are not okay. They waste precious time and money. They demotivate participants and make them wonder if leaders know what they are doing. Worst of all, they can lead to terrible decisions that put careers or entire organizations in jeopardy.

By contrast, great strategic conversations can be powerful moments of impact that drive positive change in an organization.

- They generate novel insights by combining the best ideas of people with different backgrounds and perspectives.

- They lift participants above the fray of daily concerns and narrow self-interest, reconnecting them to their greater, collective purpose.

- And they lead to deep, lasting changes that can transform an organization’s future.

The authors wrote Moments of Impact because they want to eradicate as many time-sucking, energy-depleting strategy meetings as possible – and replace them with inspiring and productive strategic conversations. They aim to deliver the single most useful resource for managers and leaders who need better strategic conversations – now – to shape the future of their organizations for the better.

Strategic Conversations: The Third Way

Faced with a tough challenge that calls for collaboration – such as increasing competitive pressures or a shift in business models – most leaders will reach for one of two well-worn devices: the standard meeting or the brainstorming session. While both are fine in many situations, neither is sufficient in dealing with messy, open-ended challenges.

There has to be another option – and thankfully, there is. Strategic conversations are the third way. A strategic conversation does not feel like a regular meeting or a brainstorming session. It is its own distinctive type: an interactive strategic problem-solving session that engages participants not just analytically but creatively and emotionally.

Strategic conversations can take place in formal or informal settings – from a board meeting to a casual retreat. They can be workshops, working sessions, or a module within a regular meeting. Most of the time, they involve at least five to ten people and at least half a day. Their defining features are that the stakes are high, the answers unclear, and the participants are expected to create real insights together – rather than play out prepared scripts across organizational boundaries.

Here are a few examples of the kinds of open-ended, high stakes situations that call for strategic conversations:

- A product development team trying to find “the next big thing” for its customers.

- An HR executive wanting to engage the organization in crafting a talent strategy.

- A business unit leader looking for ways to expand in a slow-growth environment.

- A management team trying to understand how global forces could affect their industry and markets.

Welcome To “VUCA World”

The world is changing fast these days. Unforeseen turbulence has become such a constant feature in our world that military planners have an official term for it. They call it VUCA World – an environment of non-stop volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity.

Pure Digital Technologies – the makers of Flip Video – offers a vivid example of how market directions can shift in VUCA World. Two entrepreneurs — working out of a small office in downtown San Francisco – set out to create an ultra-cheap video recorder that anyone could use. The first mass-market Flip camera, which could upload videos directly by USB drive, came out in 2007. It cost a bit over $100 and became the top-selling camcorder on Amazon.com within weeks of its launch.

For the next few years, Flip owned the category of low-end camcorders, despite being copied by giants such as Sony. In March 2009, Cisco Systems acquired Pure Digital Technologies for $590 million.

Just two years later, in April 2011, Cisco closed Flip Video. By then, low-cost video was becoming ubiquitous feature inside mobile phones and cameras.

That’s how fast change can happen today: a new company can come out of nowhere and move from scrappy startup to market dominance to a massive payday and then back to oblivion in just four years. In VUCA World, organizations face constant surprises from all directions. By the time you think you’ve got an important market trend figured out, it’s already moved on.

Adaptive Challenges Calls For Adaptive Leadership

Ronald Heifetz has been a popular teacher on leadership at Harvard Kennedy School. In a series of fine books, Heifetz and his colleagues draw a fine distinction between technical and adaptive challenges that’s critical to understand in navigating VUCA World. It’s foundational to the strategic conversations approach.

- Technical challenges involve applying well-honed skills to well-defined problems – such as building a bridge or organizing a production line. Technical challenges may be complex, but they can still be resolved within well-understood boundaries. In these situations, more traditional, hierarchal approaches to leadership work well.

- Adaptive challenges, by contrast, are messy, open-ended, and ill-defined. In many cases, it’s hard to say what the right question is – let alone the answer. Many of the most strategic challenges that organizations wrestle with today are adaptive challenges.

It’s nearly impossible for any one senior executive – or small leadership team – to solve adaptive challenges.

- They require observations and insights from a wide range of people who see the world and your organization’s problems differently.

- And they require combining these divergent perspectives in a way that creates new ideas and possibilities that no individual would think up on his or her own.

Navigating and solving adaptive challenges demands a different set of leadership muscles – such as penetrating questions, winning the full engagement of colleagues, and connecting insights from different sources in real time. While some leaders develop these skills over time, they are rarely the focus of business school programs or annual performance reviews. Because these skills are less familiar, leaders often try to analyze their way through adaptive challenges instead.

Strategy Is The Conversation

Richard Rumelt is a professor at the University of California Anderson School of Management, has been writing, teaching, and consulting about strategy for four decades. His book Good Strategy/Bad Strategy provides a sweeping overview of strategy today. It’s not pretty.

Unfortunately, good strategy is the exception, not the rule. And the problem is growing. More and more organizational leaders say they have a strategy, but they do not. Instead, they espouse what I call bad strategy. Bad strategy tends to skip over pesky details such as problems. It ignores the power of choice and focus, trying instead to accommodate a multitude of conflicting demands and interests… Bad strategy covers up its failure to guide by embracing the language of broad goals, ambitions, and values.

Amid all this flux and change, there is one constant. If you want to make progress against adaptive challenges, you have to harness the best thinking and judgment of your best people – especially when they don’t agree. The old saying is true: nobody is as smart as all of us. Plus, it is a lot harder to put strategic decisions into action if the people executing them are not part of the conversation.

Leaders thus face a world-class dilemma: they need to make good strategic choices under uncertainty while engaging more people with different perspectives, more effectively, in the process – and do it all faster.. To do this well, we’ve got to put the people back into strategy – in a much smarter way. Today, more than ever, strategy is the conversation.

DESIGNING A STRATEGIC CONVERSATION

You probably already know how to run a pretty good meeting. You know:

- That you need clear objectives that are reasonable given the time you have.

- That you should invite participants who can help meet those objectives.

- That your content – presentations and reports – should lay out the issues clearly.

- That the venue should be the right size for your group to contain the necessary equipment and supplies.

- That your agenda should end with next steps, roles, and responsibilities.

This basic model works well for the vast majority of meetings. But not when it’s time to have an important conversation about critical yet ambiguous issues. That’s when you need a powerful tool.

The authors met Marcelo Cardoso in their far-flung search for black belt practitioners of strategic conversations. At the time, he was the executive vice president for organizational development and sustainability at Natura, a personal-care-products company based in Brazil. Founded in 1969 Natura is one of the most successful companies in South America.

Part of Cardoso’s role at Natura was to convene senior executives to work through the company’s adaptive challenges. During the authors’ interview, Cardoso’s comments about strategic conversations were insightful and nuanced. Toward the end, he had a confession to make. His most recent conversation had not gone well, and he knew why.

Natura’s board and executive committee had come together to think about the brand values and qualities that tie together their major product lines. Brand strategy is a complex, systemic, and open-ended puzzle that cannot be resolved by analysis alone. It’s a classic adaptive challenge that calls for a well-designed strategic conversation.

Reflecting on the session, Cardoso realized that he’d made two mistakes:

- First, the session took place in the same room where the company holds all of its standing board meetings.

- Second, the brand strategy conversation had been wedged into the agenda between two routine board topics.

These two choices invited participants to revert to their “default settings” for meeting interactions. The managers delivered conclusion-driven presentations instead of teeing up provocative questions for conversation, as they’d been asked to do. This approach invited board members to kick into evaluation mode and look for holes to poke in the managers’ reasoning.

The session was by no means a disaster – just a missed opportunity. There was no moment of impact. Cardoso says: “We ended up having a regular performance review meeting instead of a strategic conversation.”

When bringing people together, you have three main tools in your professional tool kit:

- a standard meeting

- a brainstorming session

- a strategic conversation

Each is good for different things. The key is knowing when to reach for which tool.

It’s critical to recognize early on when you are facing an adaptive challenge, to call this out explicitly, and start designing your session as a strategic conversation. Then be prepared to hold your ground when the inevitable forces of inertia emerge, pushing you back toward the more comfortable – and less effective – standard meeting approach. If you don’t, you’re accepting a high risk that your session will yield the standard “okay” results.

Tapping Into The Power Of Design

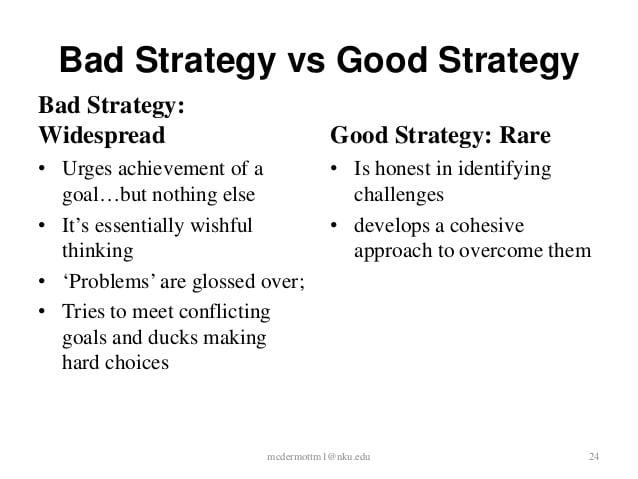

Back in mid-1990s, Apple was struggling for survival. By 2012, it had risen to become, for a time, the largest public enterprise in the world. This put Apple in an elite club that includes General Electric, IBM, and ExxonMobil.

While many reasons lie behind Apple’s dizzying success, design leadership is high on the list. Steve Jobs and his colleagues have given the world an elaborate and highly profitable schooling in the power of design.

Design is an approach in problem-solving that strives to address user needs – often unarticulated ones – through disciplined creativity. Great design is about crafting new solutions that seamlessly integrate form and function.

Well-designed products, services, buildings, and websites don’t just look nice; they work smoothly and feel good – often in ways that you can sense intuitively but may have a hard time explaining. This effect can be found in the way a Michelin-star restaurant delivers a seamless dining experience. And it can be found on Zappos online shoe store, when it serves up options uniquely tailored to your taste. Great designs delights and amazes us. It delivers solutions we didn’t know we wanted – but we get immediately.

Designers come to these elegant solutions by an emergent, craft-based process that follows a number of core principles – and few hard rules. These principles include:

- Developing a deep understanding of – and empathy for – users and their needs.

- Cycling through periods of divergent thinking to explore diverse sources of inspiration.

- Learning through quick-and-dirty prototyping of potential solutions and adapting them in response to user and market feedback.

- Testing these solutions with a small number of users first, scaling them only after they’ve proved robust.

While design is a rigorous problem-solving discipline, it can feel random at times because it often involves looping backward and trying new combinations of ideas, many of which will fail. The process appears messy not because designers are unruly but because the challenges they’re trying to solve are messy. Imposing too much structure on the search for solutions would stifle creativity.

Designers are, in short, trained to navigate their way through a world of adaptive challenges.

Writes Jeanne Liedtka, a professor at the University of Virginia who has studied the convergence of strategy and design: “Successful designers – in business or the arts – are great conjurers. A capacity for creative visualization – the ability to ‘conjure’ an image of a future reality that does not exist today, a future so real that it appears to be real already – is central to design.”

In our VUCA World, organizations need to find new ways of responding to adaptive challenges. They need to get comfortable with ambiguity and seek insight from a broader range of places. They need to continuously frame and reframe not only their answers but also the questions they pose. They need, in short, to approach strategy less like mechanics and more like designers.

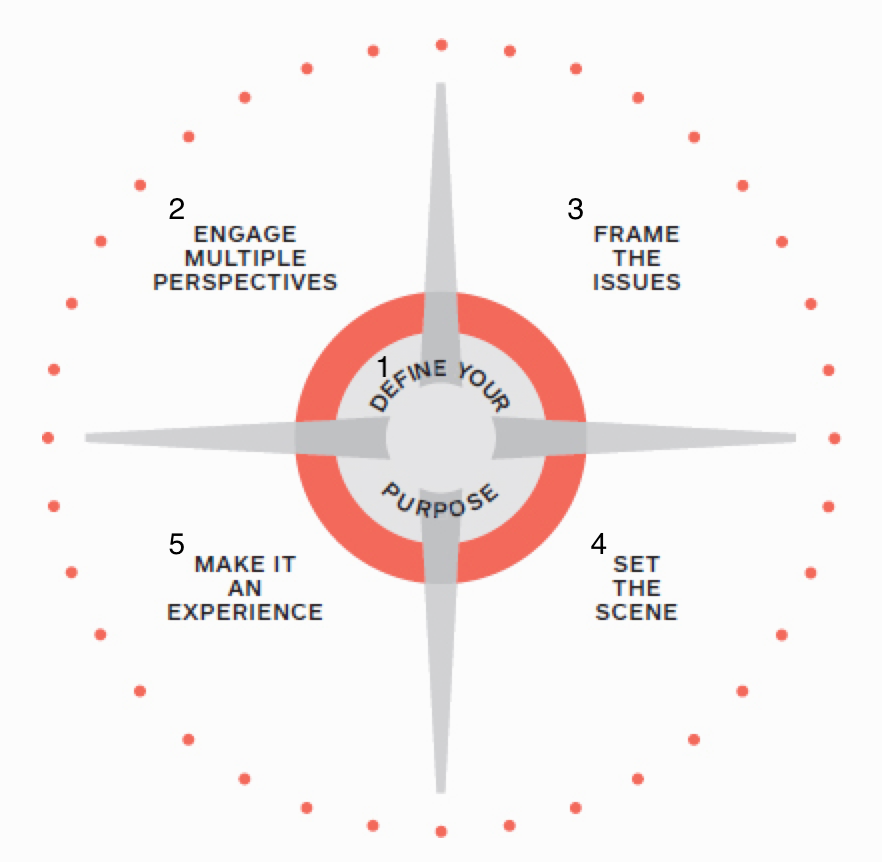

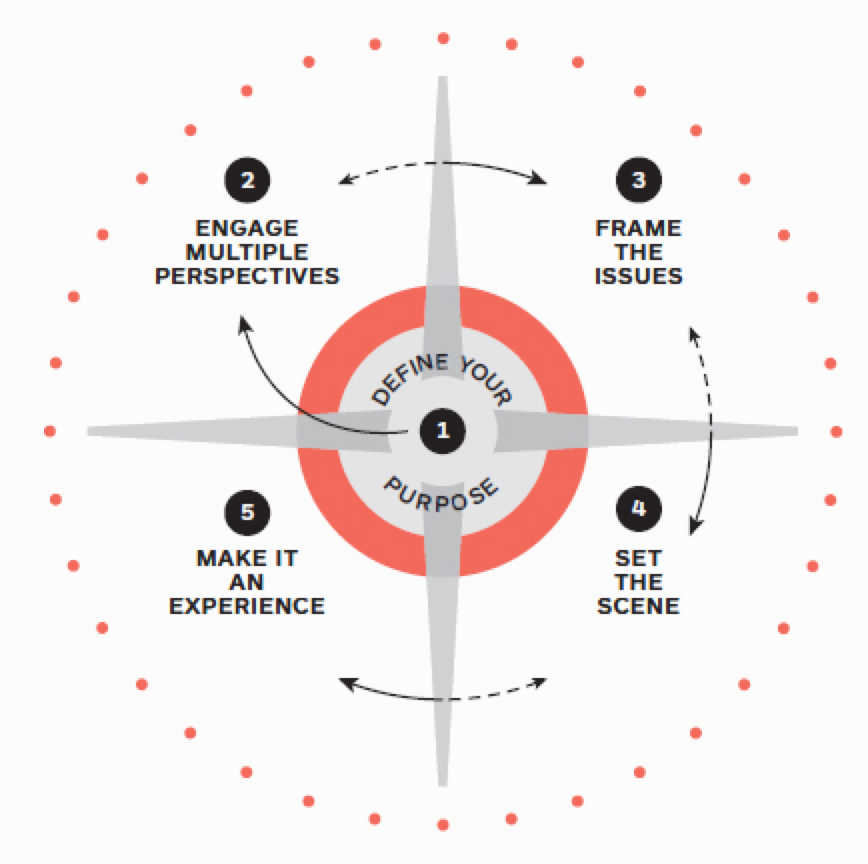

The Five Core Principles Of A Well-designed Strategic Conversation

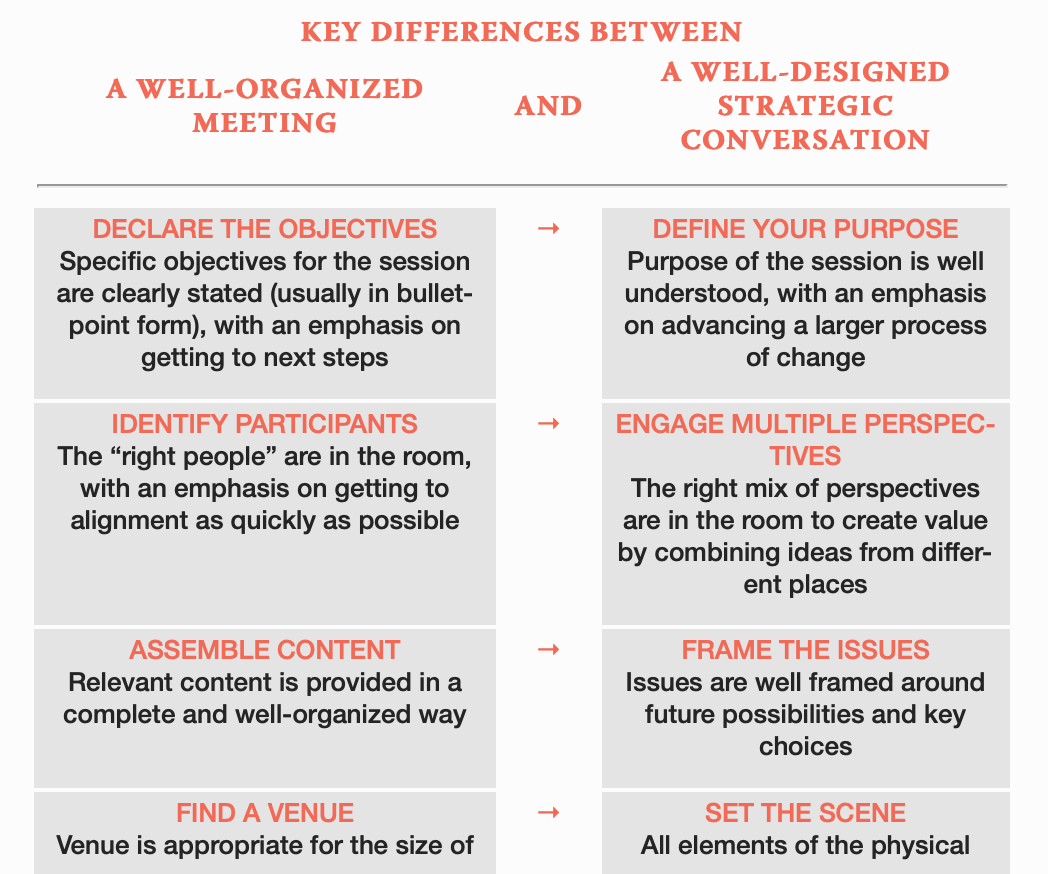

Designing an effective strategic conversation requires that you cover all the basics of a well-organized meeting – and a good deal more.

- But what is “more” exactly?

- What does it mean to design a strategic conversation?

Designing a strategic conversation means creating a shared experience where the most pressing issues facing an organization are openly explored, from a variety of angles.

- An experience where all the assumptions that make up your mental maps about how the world works – and how it is changing – are examined.

- An experience where new stories about your future success are explored, tested, and refined.

- An experience that engages a group in a deeper level of discussion than they thought possible.

The five core principles shown in the graphic illustration above are the main components of the process for designing strategic conversations.

At first glance, they may seem like the subtle refinements of the elements of a well-organized meeting. But they are much more than that.

Designing A Strategic Conversation – Core Principle 1: Declare The Objective > Define The Purpose

- A well-organized meeting requires that … you start with a clear set of objectives and desired outcomes that make sense and are realistic given the time available. These are usually expressed as a block of bullet points and shared at a meeting’s outset. At the end of the session, the group can look at the list and see whether they have accomplished their goals.

- On the other hand, a well-designed strategic conversation also requires that … you develop a clear sense of the change that this group of people needs to make together – and how this conversation will advance that process.

Because adaptive challenges are rarely (if ever) “solved” within one session, you need to understand the purpose of each strategic conversation in the context of your organization’s larger change efforts.

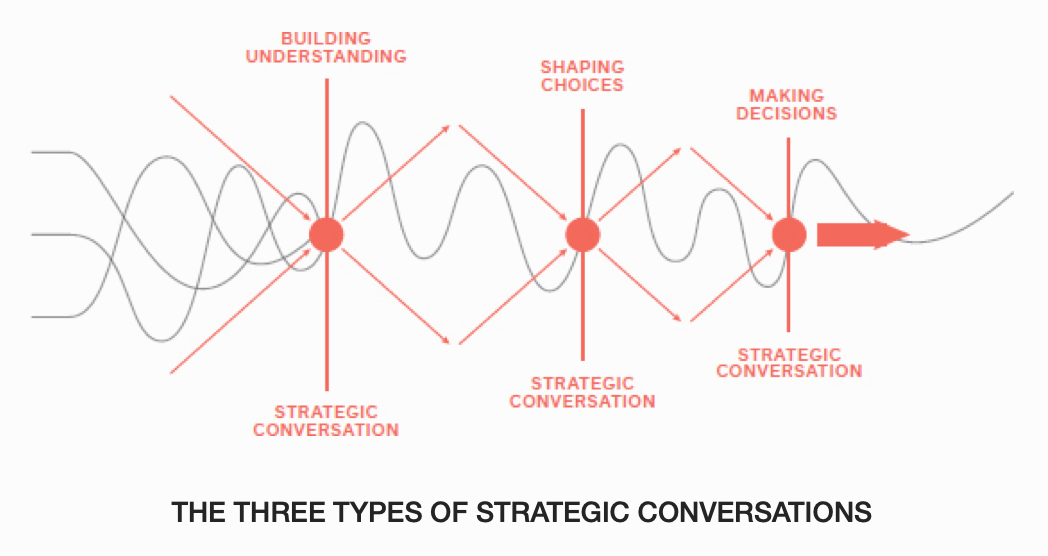

At the highest level, there are just three reasons to call a strategic conversation:

- Building Understanding

- Shaping Choices

- Making Decisions

Any session must focus on one – and only one – of these goals.

Designing A Strategic Conversation – Core Principle 2: Identify Participants > Engage Multiple Perspectives

- A well-organized meeting requires that … you identify the most appropriate participants for a given session and prepare them well in advance.

This means thinking about which leaders, decision-makers, and issue experts need to be in the room.

It also means identifying any potential sticking points and “pre-wiring” these issues with participants in advance.

- On the other hand, a well-designed strategic conversation requires that … you dig deeper to understand the views, values, and concerns of each participant and stakeholder group.

It requires that you find where opinions are aligned on the key issues and where they are not.

And it requires that you think hard about which perspectives (not just people) must be represented, such as customers or employees who won’t be in the room.

Ultimately, it requires that you find ways to create value from the intersection of diverse perspectives, experiences, and expertise that live inside any organization.

Designing A Strategic Conversation – Core Principle 3: Assemble Content > Frame The Issues

- A well-organized meeting requires that … all content be highly relevant to the objectives and clearly communicated. Reading and handouts should be focused on creating a common understanding of the issues or posing questions for participants to think in advance.

Live presentations should deliver clear findings and present options or strong recommendations.

On the other hand, a well-designed strategic conversation requires that … the content and issues are framed in a way that illuminates different aspects of the adaptive challenge you are wrestling with, including how the various parts relate to the whole.

These frames should help participants get their heads around a great deal of complexity, thereby accelerating insight and alignment.

A good frame helps make insights “stick” and thus accelerates progress on tough issues.

Designing A Strategic Conversation – Core Principle 4: Find A Venue > Set The Scene

- A well-organized meeting requires that … you find an appropriate venue given the size of your group and the nature of the meeting. Participants should be comfortable in the environment and have all the equipment, supplies, and other materials needed to support their work together.

- On the other hand, a well-designed strategic conversation requires that … you make thoughtful choices about all the elements of the environment – from the physical space to artifacts and aesthetics.

The room setup and seating arrangements should send a message about how participants are expected to relate to one another.

Food and other comforts should be consistent with the tone of the session. Like a great theater production, all the parts should come together in a seamless and integrated way.

Designing A Strategic Conversation – Core Principle 5: Set The Agenda > Make It An Experience

- A well-organized meeting requires that … you follow a logical sequence of agenda items, typically starting with some form of orientation and ending with next steps.

With each agenda item, it should be clear what topic(s) each item addresses and how it contributes to the objectives.

By the end of the meeting, all participants should know exactly what they need to do next and why.

- On the other hand, a well-designed strategic conversation requires that … you attend to the emotional and psychological experience of the participants. The experience should not only be logical but also intuitive and energizing. It should tap into participants’ full capabilities and perspectives – their logical and emotional, analytic and creative, selves.

A strategic conversation is not just an intellectual experience – it’s an exhilarating and memorable experience.

The Well-organized Standard Meeting: Hitting The Bull’s Eye When The Goal Is Clear

Organizations are like archers. Most of the time, organizations consists of a collection of people going through motions they have done many times before in order to produce a reliable result. Likewise, running a standard meeting can feel like aiming at a bulls-eye. Your goal is to focus all your energy and resources on a pinpoint objective, such as a marketing plan or a quarterly budget. For most technical meetings, the standard meeting approach works fine.

Except when things change or when adaptive challenges sets in. Such as when your customers lose interest in what you are providing. Or when a technology threatens to reshape your industry. At times like these, an organization can find itself aiming at a target that has moved when you were not looking.

The Well-designed Strategic Conversation: Finding Your Way When The Path Is Not Clear

When adaptive challenges arise and clear targets are hard to spot, you need something different to help you find your way. Something more like a compass.

With adaptive challenges, the nature of your interactions will play a huge role in determining how you resolve them. Real strategy happens in human conversations, not on lifeless spreadsheets and software.

The five core principles will help you design strategic conversations for better outcomes.

These principles can also be seen as the five steps in a design process. But while each of the core principles is numbered – you do not have to complete each step and then move to the next one in a linear way. It is inevitable that you will have to go back and forth among the principles as your design unfolds. The way you frame the issues might change your ideas about who needs to be in the room.

As you get the hang of designing strategic conversations, you will no doubt develop refinements that work best for you. Use this process and tool kit as a platform to get on the path of mastery – and to make it your own with each new conversation.

Below is a summary of the critical differences between a well-organized meeting and a well-designed strategic conversation.

Define Your Purpose

There is a great scene in the movie Moneyball, based on the nonfiction book by Michael Lewis. Billy Bean (played by Brad Pitt) is the general manager of the Oakland Athletics baseball team. It’s the 1991 offseason and the A’s are coming off a good year; they won 102 games and fell just short of making the playoffs. But now they face a serious problem. Their three most valuable players have all defected to other teams for more money.

In the scene, a bunch of old school talent scouts sit around a conference table sharing ideas about how to replace the three stars. After listening to a rehash of options they have clearly discussed many times before, Beane loses his patience.

Beane: Guys stop. You’re talking like this is business as usual. It’s not.

Grady Fuson (a scout): We’re trying to solve the problem.

Beane: Not like this. You’re not even looking at the problem.

Fuson: We not only have a clear understanding of the problem we now face, but everyone in the room has faced similar problems countless times before.

Beane: The problem we’re trying to solve is that this is an unfair game. There are rich teams, poor teams, and then there’s us. And now we’ve been gutted. We’re organ donors to the rich. The Red Sox took our kidneys and the Yankees took our heart.

Beane is trying to have a strategic conversation with his crew. But while they appear to be working on the same problem – building a winning team for next season – they’re not. From Beane’s perspective, the A’s cannot beat the rich teams by using the same talent strategy but with far fewer resources. The scouts disagree.

The scouts see the A’s problem as a technical challenge calling for tried-and-true approaches.

By contrast, Beane sees it as an adaptive challenge requiring creative problem-solving. Beane is right! The only hope the A’s have is to find a different approach to filling their lineup. But the problem is so familiar that the scouts are unable to think about it differently. They are trying to hit the same old bull’s-eye with the same old arrow when what they really need is a compass to help them find their way.

But adaptive challenges cannot be solved in one strategic conversation. In Beane’s case, he undergoes a process of exploration and discovery – through a variety of activities and discussions – that leads him to a radical new strategy. Ultimately, and against heavy resistance from his scouts, he uses advanced data-mining techniques to find “hidden gem” players overlooked by other teams. He succeeds in building a winning team with a puny payroll – forever changing baseball’s marketplace for talent.

Define Your Purpose, Key Practice 1: Seize Your Moment

Imagine that your organization is facing a thorny adaptive challenge. Maybe an aggressive new competitor is stealing your market share, or an attractive but complicated growth opportunity is opening up.

Many organizations respond to the inherent messiness of adaptive challenges by trying to tame them with a highly structured process that’s more in their comfort zone. But challenges like the one Beane faced cannot be tackled with Gantt charts and Six Sigma methods. They call for creative problem-solving similar to the kind that designers have long used to coax clarity out of ambiguity.

Once an organization recognizes that it is facing an adaptive challenge, it typically sets out on a winding road of exploration, discussion, and action that eventually leads to decisions and results. This larger process of strategic exploration and discovery can unfold over a few months. It comprises many different interactions and touch points that unfurl over time, including informal discussions, intensive research, formal review meetings, working-team sessions, and most important – strategic conversations.

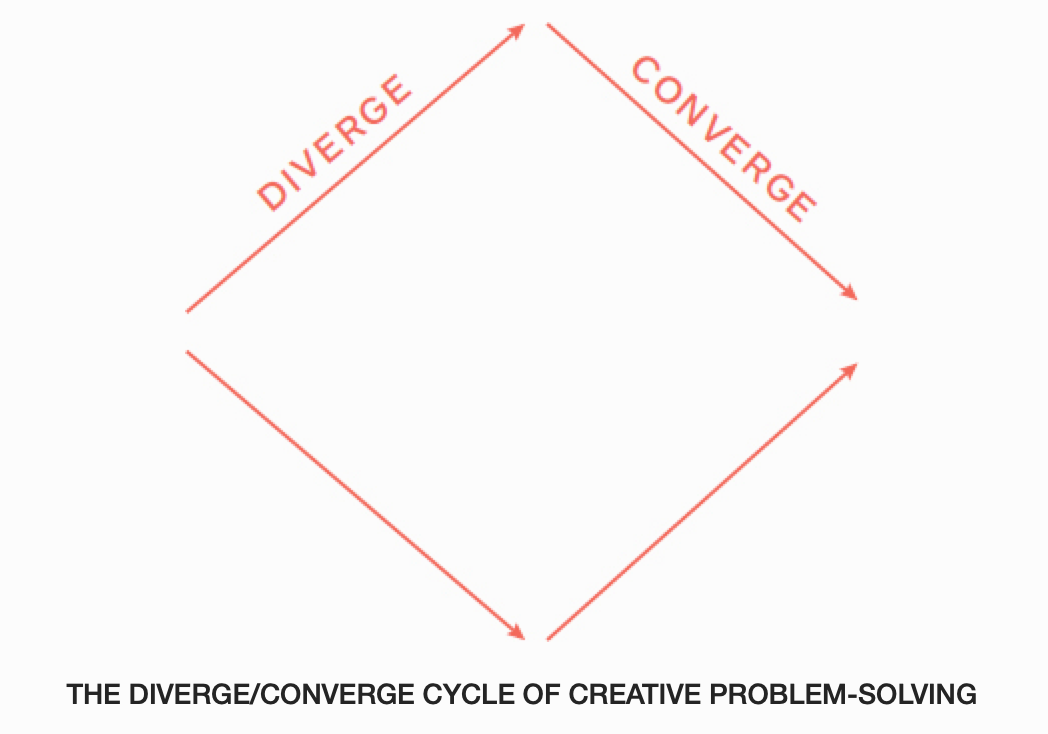

At its simplest level, this kind of creative problem-solving follows an arc of divergence and convergence as shown in the diagram below. You start by taking a broad perspective on a challenge, then gradually shift into identifying and winnowing down possible solutions over time.

Let’s say that your organization is behind the curve on social networking and assigns a team to figure out what to do. The team will likely start with a narrow technical definition of the problem – such as how to develop a better presence on Facebook and Twitter. But as the team probes more deeply they realize the issue is more complicated.

- What kind of communication does the organization want with its customers?

- How open is it willing and able to be with them?

Such questions lead them to thinking about overall brand strategy, which raises the question of which market segments will be most vital to driving growth.

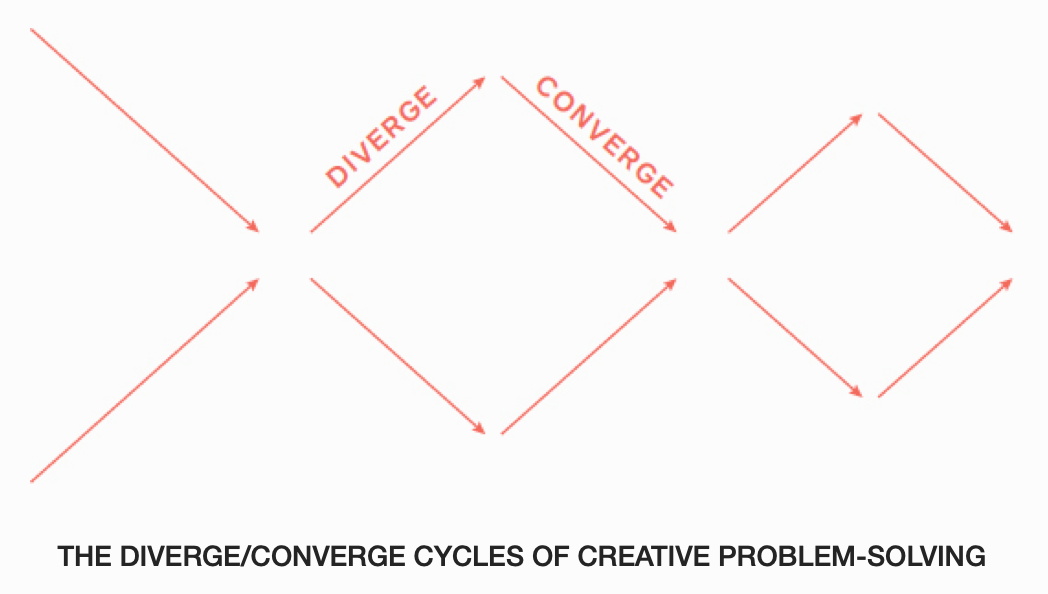

As a result, their process ends up looking more like the diagram below with several diverge/converge cycles. The team widens and narrows their scope of inquiry at different points, with a trend toward narrowing over time. What’s hard to predict is exactly when they will need to diverge, since each cycle is driven by new insights along the way.

Define Your Purpose – Key Practice 2: Pick One Purpose

Ana Meade is a strategic planning manager for Toyota Financial Services (TFS) – the people who arrange financing when you buy or lease a Highlander or a Prius. An important part of her job is organizing meetings and strategic conversations. A few years ago, firm leaders felt that they were spending a lot of time in unproductive meetings. So the company launched a task force to see what could be done.

One of the improvements they came up with was a simple, one-page form requesting time with senior leaders. At the top of the form was a big space where would-be presenters could declare the purpose of their meeting. They were required to check one – and only one – of the following boxes:

- FYI

- Input (i.e. requests for guidance and feedback)

- Decision

Says Meade who helped implement the plan once it was in place: “We got a lot of pushback from people who wanted to go to the executives with more than one purpose. We had to persuade people that they could really only pick one … Some people also had the sense that every meeting had to have a decision involved, which is not the case.”

Ultimately, this small innovation forced presenters to be clearer in their requests and helped firm leaders to know what was expected of them in each interaction. Meetings with TFS executives got a lot more focused and productive. Says Meade: “Just having this question on the form has had a huge impact. It provides clarity for everyone.”

While there are infinite reasons to bring a group together, strategic conversations have just three overarching purposes:

- Building Understanding

- Shaping Choices

- Making Decisions

Any strategic conversation you can imagine will sort into one of these categories. A well-designed strategic conversation must focus on one – and only one – of these three types.

Three Types Of Strategic Conversations:

Choose The Right Purpose For The Moment

Because a strategic conversation consists of live interactions between people with different perspectives and passions, you can never predict exactly where it will lead. Still, you must start your design process knowing what kind of outcome you expect – without overspecifying the content of that outcome.

The first question to consider is which kind of session you need to run at this time.

- If your group does not know much about the issues – or has sharply divergent opinions on them – you need to run a Building Understanding session.

- If they have tons of knowledge but are spinning their wheels on what to do, – it’s time for a Shaping Choices session.

- Only when you’ve done both of these jobs well – should you consider calling a Making Decisions session.

1. Strategic Conversations For Building Understanding: Pose A Clear Challenge

Building Understanding is where it all starts – the foundation of any discovery process that may ultimately resolve an adaptive challenge. It’s hard to get anywhere useful in Shaping Choices and Making Decisions unless you’ve come to some novel and relevant insights about the strategic issues that challenge your organization.

Building Understanding is hard work. Because adaptive challenges are messy and open-ended, it can be fiendishly hard to figure out how to start. It maybe tempting to bring people together to explore an adaptive challenge without a clear goal in mind. Often these sessions produce a lot of great ideas, but are not set up to accelerate real change. While such an exercise might prove great fodder for a retreat or a professional development session, it’s not a strategic conversation.

While strategic conversations for Building Understanding are exploratory in nature, it’s still critical to get somewhere concrete in the end. Rather than raising general issues for your group to kick around, you need to pose crisp challenges for them to wrestle with.

Imagine that you are an executive of a major book publisher, wrestling with seismic shifts in how books are produced, distributed, and bought. Your favorite bookstores are closing their doors one by one as e-books take off. Amazon, your fastest and largest sales channel, has decided to compete with you by publishing its own books. Some of your bestselling authors are starting to go directly to their readers by self-publishing their works. In short, you are in the middle of a classic industry transformation marked by high uncertainty and even higher stakes.

You have been charged with convening a one-day strategic conversation for a few dozen leaders about how your markets could evolve over the next three years. While your fellow executives are plenty familiar with the issues, the high degree of confusion around them makes it necessary to hold a Building Understanding session before you can think about Shaping Choices.

At first you’re excited about this high-profile assignment. As the date of the session approaches, though, your anxiety soars. So many different questions and issues must be considered – and each interview you conduct or research report you read seems to surface even more of them. You’ve only got one day to squeeze the best thinking from all these senior people – and they are counting on you to make sure their time is well spent.

After working on the content, you land on four options for describing the session’s purpose. Which would you choose?

Option 1 (business objective focus): Meeting growth and profitability goals in a changing environment. The world of book publishing is witnessing major changes across the entire business – from how books are acquired and produced to how they are distributed, sold, and read. In this session, we’ll look at how we can meet our business goals in priority markets within an environment of increasing uncertainty and change.

Option 2 (broad trends focus): The future of book publishing. The world of books and reading is undergoing major changes. In this session, we’ll look at a range of trends that could rock the publishing world, including surprising new technologies, dramatic shifts in consumer preferences and behavior, and emerging competitors.

Option 3 (business model focus): What are the most promising new business models for book publishing? Publishing’s long-standing business model is under intense pressure, even as new media platforms are creating exciting opportunities. In this session, we’ll envision some new business models that could emerge for publishing – from new entrants and established players alike.

Option 4 (reader behavior focus): How will people prefer to read in a world of unlimited choice and limited time? Consumers are being offered more and more choices for media consumption but still face the constraints of a twenty-four hour day. In this session, we’ll take a “deep dive” into recent social and consumer trends and develop hypotheses about how reader behavior could evolve in the years to come.

All of these sessions sound interesting. But you’ve got to pick one, so let’s look at their pros and cons:

- Option 1 asks participants to “follow the money” and focus their attention on profits and growth. It sounds tempting – but this focus is too narrow. As with Billy Beane’s baseball scouts, this statement of the problem invites people to round up the usual ideas. While Option I offers the benefit of a strong business focus, it’s unlikely to inspire much creative thinking.

- With its focus on “the future of book publishing,” Option 2 is the broadest. At first glance, this sounds creative. But spending a day looking at all these trends without a clear focus is likely to result in interesting but aimless discussion, after which participants simply get back to their “real work.”

- Options 3 and 4 are much better. That is because they each pose a focused relevant change that demands creative and collaborative problem solving. Which of these options is better? Without knowing more about the specific situation, it’s hard to tell. And it may not even matter. Working through either of these challenges would require the group to think about the other as well. If you want to invent a new business model for publishing, you’ll need to understand changes in reader behaviors and preferences.

Look at options 1 and 2 and try to imagine where you would land at the end of the day. It’s not clear.

Now look at options 3 and 4. Each provides a concrete landing point – either specific new ideas to explore or hypotheses to test. Having a clear landing point makes it much easier to conclude a session with strong insights and next steps.

For any given Building Understanding session, there’s more than one “right” way to further define your purpose. The key is to pose a clear problem-solving challenge that both grounds the conversation and expands the group’s thinking. You’ll know your session was successful if participants leave with a common understanding of the issues, a set of hypotheses to test, a research agenda, or other concrete guidance moving forward.

2. Strategic Conversation For Shaping Choices: Convert “Issues” Into Clear Options

Once you have built a strong platform of shared understanding, it’s time to think about convening a Shaping Choices session. Action-oriented management can only take so much talk before they start itching to do something. Converting issues into choices between specific options typically unleashes a lot of energy.

Write Roger Martin, of the Rotman School of Management in Toronto, and A.G. Lafley, former CEO of Procter and Gamble: “Constructing new strategic possibilities, especially ones that are genuinely new, is the ultimate creative act in business.”

But the way that you go about creating these possibilities makes a big difference. It’s one thing to ask a group, “What should we do about social networking?” It’s another to charge them with building and testing specific models for how to tap into the power of social networking in their work.

Shaping Choices follows a classic design “funnel,” from generating rough ideas to prioritizing them all the way to evaluating and testing the best options. This requires making sense of a wide range of observations – from social and market trends to ground-level operational insights – and demands both rigorous analysis and creative synthesis.

It’s critical to have participants work at the right level of detail for where they are in the overall process.

- If you get too deep into the details when in sketch mode, you risk having the group reject some great ideas.

- If you fail to engage in sufficient detail when developing prototype options, you risk having your ideas tripped up in execution.

When Shaping Choices, your goal is to get participants toggling back and forth between drawing a picture of an inspiring future success and testing how it could work in the real world at increasing levels of specificity. Do this well through a few iterations and great things can happen.

Find (Or Create) A Structure For Fleshing Out Your Options

Roger Martin and A.G. Lafley lay out a general approach to developing and testing options. Their process is based on set of a cascading questions that can be applied to a wide range of strategic situations.

Any strategic option should have clear and interconnected set of answers to five questions:

- What is our winning aspiration?

- Where will we play (e.g. what customers will we serve)?

- How will we win (e.g. how will we deliver a unique value proposition to the market)?

- What capabilities must be in place?

- What management systems are required?

Whatever process and tools you use, it’s important to find – or create:

- A flexible yet disciplined structure that forces participants to develop whole options.

- Focuses the discussion on the key assumptions behind each option

- And makes the options tangible.

Any approach that achieves these three goals should lead to a stimulating and productive strategic conversation around Shaping Choices.

3. Strategic Conversations For Making Decisions Are Rarely Designed

This brings us to the third category of strategic conversations. Sessions for Making Decisions are rarely designed as creative and collaborative problem solving.

Why is this? The most obvious answer is that organizations are not democracies. Even the most inclusive leaders are reluctant to take a wide-open, collaborative approach to Making Decisions on their biggest strategic questions. In the majority of organizations – large or small, profit or nonprofit – pivotal choices are made by senior leaders and a handful of close confidants, not by a roomful of people in a strategic conversation.

Of course, groups of people get together to make decisions all the time – in board meetings, management-team meetings, and so on. But these sessions rarely count as genuine strategic conversations. More often, they play out in two ways: the “straw poll” or the “rubber stamp.”

- In the straw poll, a group of people who do not have decision rights are asked to weigh in on some important issues, leaving the real decisions to be made by a smaller group.

- Rubber-stamp sessions are about finalizing a decision that has been “prewired” in advance among the most powerful and connected members of the group. Everyone else is effectively there to learn what’s already been decided.

The good news is that if you do a great job of designing your strategic conversations for Building Understanding and Shaping Choices, the task of Making Decisions becomes much easier. After the first two stages, the final decision comes as an anticlimax or fait accompli. The larger group may not have a vote, but if they have had their say in one or more well-designed strategic conversations, they’ve had real influence on the outcome.

Define Your Purpose – Key Practice 3: Go Slow To Go Fast

“Creative destruction” is a central force in any dynamic modern economy.

This is the evolutionary process by which innovative firms continually replace less adaptive competitors in the marketplace. Firms that want to avoid creative destruction need to strike a balance between exploiting known ideas and exploring new frontiers of new knowledge – between hitting their goals for today and making wise investments for the future.

The right balance for any organization depends on the situation. Some markets – such as high tech – require more exploration than others. In our era, two things are certain:

- First, we still hire and reward people mainly for their ability to exploit known ideas (in other words, to tackle technical knowledge).

- Second, VUCA World is serving up an increasing number of adaptive challenges, which call for more exploratory approaches – and more people who know how to lead them.

Sara Beckman is doing her part to address this imbalance. She teaches a core curriculum class, “Problem Finding, Problem Solving,” at the University of California. In 2010, to better understand her audience, Beckman asked all 243 of her students to assess their own learning styles. What she found was that majority of students fell into the Converging category – a learning style that values analysis and formal logic to arrive at quick conclusions.

Dealing with adaptive challenges requires a high tolerance for ambiguity. But many leaders and managers steeped in the Converging style of learning (that values analysis and formal logic to arrive at quick conclusions) – are impatient with ambiguity. Change is coming at them fast, and their response can make the difference between winning and losing in fiercely competitive markets.

Yet organizations that can not muster the patience to grapple with the volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity of our times are ultimately no match for the gales of creative destruction, which sooner or later sweep away most firms.

Develop Insights Before Taking Action

When approaching a strategic conversation, it’s common for participants to push for agendas that drive faster toward agreement and decision-making than is realistic. That’s a problem because people need time and space to process together the complexity of adaptive challenges.

In the late 1990s – a time of especially rapid change in the business world – the authors designed and led a Building Understanding session with a large financial services company. The emerging Internet economy was transforming Americans’ investment behavior.

From their headquarters, this company’s leaders knew they needed to figure out how the Internet economy could evolve in the coming years. So the project team designed a three-day “learning journey” – a field trip to explore new ideas and environments – that included visits to about a dozen new-economy hot spots in the San Francisco Bay Area, including young but promising companies such as Google and Yahoo!

After three days of total immersion at the hub of the Internet economy, an additional day was planned for strategic conversations.

In the weeks leading up to the event, some participants were pushing for the agenda of the strategic conversation to drive into real action – along the lines of Shaping Choices or Making Decisions session. However, once the group completed its intense three-day learning journey, they were overwhelmed by new information and in no position to act. They needed time together to pull out a few key insights from the learning journey before these slipped away.

During the one-day Building Understanding session, the group agreed on two important insights:

- That the Internet economy was real and they needed to engage with it more aggressively, and

- That the investment climate around the Internet economy had entered a “bubble” territory which would inevitably lead to a market correction.

While perhaps obvious in retrospect, these two insights felt contradictory at the time. Getting agreement on them was a huge win.

In the months that followed, the two big insights served as the foundation for a few more strategic conversations, which led the firm toward a number of smart decisions and actions. In particular, firm leaders resisted the powerful temptation to aggressively add capacity and staff during the heady times of 1999 and 2000. As a result, when the dot.com bubble burst in 2001, they had a less painful adjustment to make than many competitors.

This result is so important and so consistent that it bears repeating. Before a strategic conversation, most participants will push for session objectives that are further downstream than the group is ready for. But during a strategic conversation, they will push back against attempts to get to outcomes that the group is not ready for.

As a designer of strategic conversations, it is your job to help nurture the patience that is required for the group to develop insights before they start taking action. This is what is meant by the phrase “go slow to go fast.” Protecting the space for the group to get some real insights before action is critical.

Next Steps Are Easy – If Your Group Is Aligned

An important part of running any good meeting or strategic conversation is getting to a clear list of next steps. Time-pressed executives are emphatic on this point because they got burned before.

Poor follow-through can plaque the aftermath of strategic conversations. Not because participants don’t know how to execute, but because the group never came to alignment at all.

Pressed for time and facing a complex adaptive challenge, the default setting in many organizations is for leaders to push people to commit to next steps before they reach true agreement or consensus. Predictably, most people play along. Inside the room, their attitude is “salute and mute,” or passive acceptance. Outside the room, it shifts subtly to “this too, shall pass,” or passive resistance. There may be a long list of concrete next steps, but there’s no commitment.

Psychologist Teresa Amabile found in her painstaking research of personal work diaries that the single biggest factor in the morale and productivity of professionals is whether they get a sense of progress from their efforts.

With strategic conversations, the most important question is what constitutes progress. Groups that make the effort to get a true moment of impact – that is, some deep alignment on important insights – recognize this as progress. After they reach this point, they can usually start taking action – fast.

To be sure, we prefer to leave a session with both strong commitment and next steps. But if we had to choose one over the other, we would choose alignment every time. If you leave a strategic conversation without consensus, no list of next steps – no matter how “action oriented” – is likely to help. By contrast, when your groups walks out of a room with genuine agreement around some important new clarity, you can always sort out next steps later.

Engage Multiple Perspectives

Adaptive challenges are too complex for any one person to figure out, and too open-ended to be solved by analysis alone. They require leaps of insight that usually come from combining ideas from different places in new ways.

Yet, too often, the default approach to collaboration amounts to a recipe for groupthink – the mortal enemy of strategic conversations.

Groupthink is evident whenever a group of people:

- shows excessive deference to leadership or consensus views,

- there is suppression of dissenting voices,

- shrinks from surfacing and testing key assumptions behind important choices.

This phenomenon has been implicated in helping the downfall of many organizations.

Groupthink can be found in all kinds of organizations. It’s what you usually get when you bring together the same people in a familiar place to solve problems in the same old way.

By contrast, serious studies of innovation and creativity highlight the importance of diverse perspectives in any search for novel solutions. This is true in art, science, and business – in historical times and in the present. Anywhere people are generating new ideas at a standout clip, you will find a rich ecosystem of diverse perspectives coming together.

Great strategic conversations do this. To get some of this magic working for you, you have to do at least three critical things:

- Bring together the right perspectives

- Create a platform for collaboration

- Carefully lean into the most important differences of opinion in a way that sets off a “controlled burn” of contained and productive conflict.

Strategic conversations can be physically and emotionally exhausting for participants. These sources of stress can be especially intense when the issues are important, the participants don’t know one another well, or their perspectives are widely divergent.

As a designer of strategic conversations, a critical part of your job is to find ways to offset and manage these stresses by creating a common platform to support creative collaboration. In meeting-speak, people often talk about “level-setting” a group – or making sure they start from a shared information base. While that is important, from the authors’ experience it’s just one of eight “key planks” that make up a strong common platform for strategic conversation.

Eight Key Planks To A Common Platform

- A sense of shared purpose and objectives.

- A sense of group identity and community.

- A common understanding of the challenges.

- A sense of urgency.

- A shared language system or common definition of key terms.

- A shared base of information to draw upon.

- The capacity to discuss tough issues.

- Common frames through which to see the issues.

Frame The Issues

The Picture On The Puzzle Box

Strategic conversations require participants to take a great deal of information and observations from a variety of sources and perspectives, all at the same time. But to make progress on adaptive challenges, you as the strategic conversation designer need to do more than just gather all the relevant data for them. You need to make smart choices about where and how to direct their attention within this mass of complex and often conflicting signals.

As the word suggests, a frame is a strong focusing device – a set of operating instructions for the mind on. Good frames for strategic conversations turn your attention to what matters most while lighting up your peripheral vision at the same time. If you’ve ever been part of a strategic conversation that floundered, odds are that poor framing was one culprit. Bad frames can blind you to important signs of change that are right in front of your nose.

As a strategic conversation designer, an important part of your job is to frame (and reframe) the issues in a way that directs the attention of your group in productive ways.

- If your group has a tunnel vision on a problem, then you need a broadening frame or two.

- If they are overwhelmed by data and complexity, you need a frame that narrows.

- If they see only the risk ahead of them, you will need a frame that helps to highlight opportunities as well.

When practical, it is best to identify your key frames well in advance of your session. This will help you make clearer and smarter choices about which content to include – and, just as important, what to leave out.

Framing The Focal Question

If you had a life-threatening cancer and were offered an operation with 90 percent chance of curing the disease, would you take it? What if you were told that there was one-in-ten chance you would not survive for long after the procedure?

These questions ask the same thing but they are framed differently. People are far more likely to respond positively to the first version of the question, which highlights the opportunity, than to the second, which highlights the risk.

Pollsters have known for ages that the way that you frame a question can have major impact on the answers you get. This observation also applies to strategic conversations, where a well-framed question can be one of your most powerful tools. As Charles Kettering, the American inventor famously said, “A problem well stated is a problem half solved.”

When deciding a strategic conversation, deciding what problem you are going trying to solve is one of the most important choices you will make – and one worth spending a great deal of time.

While there is no right or wrong way to go about this, it is usually helpful to draft three or four candidate focal questions that would steer the conversation in slightly different directions (similar to the different problem statements on the future of book publishing.) Then you can test these options with a few key people to see which one sparks the most productive reactions.

Resist the temptation to compromise by merging the questions into one high-level, all-inclusive discussion.

Frames That Propel The Conversation Forward

You need to be aware of another frame – and in some ways it is the most critical. After a strategic conversation, the last thing you want is to have that momentum come to a screeching halt. To stop that from happening, you need an output frame. An output frame is the bridge between what happened in the session and what needs to happen next. It creates a through-line from a strategic conversation to the next step in the journey.

Unless you work at a small organization, chances are that only a subset of the people who will be driving your session’s results participated in your strategic conversation; many other employees and investors will need to get clued in on board, too. However, participants often struggle afterward to convey the content and the feel of a strategic conversation to those who were not there, often resorting to slide-show summaries. Good output frames can overcome this challenge by translating the experience and insights of a session through a metaphor, visual, or story that those who were not there can absorb and use.

As Michael Schrage, a prominent consultant on strategy and innovation puts it, “The whole purpose of a strategic conversation is not just to have a good conversation about strategy. It’s about getting to a framework for the alignment of behaviors that help you get to the outcomes that you need.”

When designing your next strategic conversation, you’ll want to spend serious time thinking

in advance about both your input frames – how you are setting up the problem and content of the session – and the kind of output frames you hope to leave with. As your frames get smarter and more evolved, so should the choices and actions your group makes as a result.

Set The Scene

WHEN ALL THE SMALL PARTS COME TOGETHER, IT GETS PARTICIPANTS’ ATTENTION

Walk into a room in which a strategic conversation will take place, and you will quickly pick up subtle clues about what’s about to happen – for better or for worse.

- Is the room set up for open dialogue or passive listening?

- Are the tables and chairs arranged to reinforce hierarchy or level it?

- Do the small touches signal that this is a special event where anything could happen – or just another day at work?

- Is this room where people will do hard work together – or just multitask by the side?

Most people can grasp out the above in mere seconds just by seeing how the scene has been set. Unfortunately, what they see is usually not encouraging or inspiring.

Most organizers ask themselves “Do we have everything we need?”

Strategic conversation designers ask a different question first: Where and how can we create the best environment for creative collaboration?

They are fussy about picking the right kind of space – and then work hard to make it their own. They create opportunities to tap into visual thinking throughout the session. And they obsess over nailing the details.

It is possible to set a great scene at any budget level and in any space that’s got the basic checklist of basic requirements (see below). Doing so requires taking responsibility for the total environment in which participants will be working. Strategic conversation designers don’t just do it because it’s nice: they know from experience that it can make a huge difference to the final outcome.

Checklist Of Basic Room Requirements For Strategic Conversations

- Pick a room that works:

- Size: Doesn’t feel cramp or cavernous.

- Shape: Allows everyone to see and be easily seen.

- Space: Works well for both plenary and breakout sessions with ample open space.

- Windows: Let the sunshine in.

2. Can be easily adapted:

- Furniture: Movable, supporting quick set changes as needed.

- Writing surface: Gives participants space to write, doodle, and work out ideas on paper.

- Clear wall space: Enough to hang posters, timelines, templates, or other materials that need to be visible at all times.

3. Comfortable and free from distractions:

- Seating: Comfy and breathable.

- Room temperature: Controllable and reasonably set.

- Acoustics: Everyone can hear everyone else clearly, with no distracting noises in the background.

- Minimal visual distractions: No visual craziness such as psychedelic carpets, bad art, cluttered storage piles, or busy traffic.

The Dark Side: Confronting The “Yabbuts”

Now that you are familiar with how to design strategic conversations – and have seen how they can lead to moments of impact, it’s time to visit the dark side.

By this point, you might have collected a number of yabbuts in your head. That’s the word that innovation strategy pioneer Larry Keeley uses to describe thoughts like: “Yeah, sure this sounds all good – but here is why this would never work in my organization.

The authors studied all the “moments of non impact” they could find and uncovered a few clear patterns. Most of the time, when a session flops, it is because it fell victim to at least one of big three yabbuts:

- Politics

- Near-termism

- And what the authors call “karaoke curse”

The Dark Side, Yabbut 1

POLITICS

The phrase political organization is redundant; all organizations are political. Every participant in a strategic conversation brings self-interest to the table, even if few of them will talk about it freely.

How Organizational Politics Work

The authors suggest you read Art Kleiner’s Who Really Matters: The Core Group Theory of Power, Privilege, and Success – a tour-de-force analysis of how organizational politics work. Kleiner’s book delivers two main takeaways for strategic conversations.

First, leadership teams do not make the big decisions. At the top of every organization – and many units – sits a group called the executive committee or leadership team. But these teams are rarely decision-making bodies. Rather, they exist so that people who head up these various units and functions can coordinate their activities – a worthwhile but different purpose.

The second big insight is that, while there is no such thing as “no politics,” there is a continuum that runs from “bad” to “good.”

Bad politics is about individual self-interest, control over resources, and empire building. Gaining and retaining power – and enjoying its many perks – is its own end.

Good politics, by contrast, involves honest debate about ideas, values, and an organization’s direction.

It’s usually easy to tell whether an organization tilts toward good politics or bad.

When you interview executives at an organization where bad politics rule, their comments tend to feature elaborate relationships for why their unit, department, or team is doing well, while all problems lie elsewhere. They cannot stop positioning and positioning.

By contrast, when you interview executives at a place where good politics dominates, their comments are focused on big-picture issues – what customers are saying, which trends are driving change in the markets, and so on. When they talk about internal issues, it is more in the spirit of trying to understand complex personalities and group dynamics rather than gaming them.

To be sure, there are many shades of gray in between. Most people will enter a strategic conversation with mixed motives. Even “good” politicians must work to gain and retain power in order to be effective. The key is to keep a watchful eye for common political pitfalls and address them in ways that can steer a strategic conversation away from bad politics and toward the good.

The Dark Side, Yabbut 2

NEAR-TERMISM

In 2006, MySpace, the popular social networking site, was an online behemoth, with more visitors than Google. Until 2009, it was neck and neck with Facebook in a race to become the planet’s dominant social media platform. But when MySpace and Facebook started pursuing sharply different growth strategies, their paths split – for good.

Facebook’s strategy was to invest in new ways to delight its users; its teams spent a ton of time studying social networking behavior and using that data to participate – and create -what Facebookers would want next.

MySpace chose to focus on near-term metrics in order to shore up the company’s stock price. While Facebook kept rolling out new user-friendly features, inspiring members to join by the millions, MySpace grew so busy with ads that its once-loyal users started flocking elsewhere.

In 2011, News Corporation sold MySpace for just $35 million – a sharp discount from its purchase price of $580 million in 2005. The following year, Facebook went public, having breached a billion users globally and annual revenues of nearly $4 billion.

MySpace is hardly the first or the last company to learn that a close-in focus can shortchange the future. In today’s rapidly changing environment, all organizations need to balance short-term goals with long-term growth if they want to thrive beyond the next few quarters. Yet only a handful of organizations are true masters at this balancing act.

This short-term bias cascades down an organization. While leaders give lofty speeches about visions for the future, the metrics they create and enforce tell people what really matters: near-term performance.

When you are taking sharp curves at a hundred miles per hour, mistakes are far more likely to be fatal.

The Dark Side – Yabbut 3

THE KARAOKE CURSE

While we have more natural aptitude for some things than for others, raw talent does not amount to much without a lot of effort. Books by Malcolm Gladwell (Outliers) and Geoff Calvin (Talent Is Overrated) show that – time after time – people who appear to have amazing “natural talent” turn out to have put in at least ten thousand hours of deliberate practice.

Karaoke skills is the authors’ term for areas where people’s confidence tends to exceed their competence. Driving is a classic “karaoke skill”: surveys show that a vast majority of people rate themselves as “above average” as drivers. By contrast, a few things that are definitely not karaoke skills are brain surgery, gymnastics, firefighting. If you rarely or never do these things, you will not kid yourself that you are good at them.

Strategic conversations tend to surface a number of karaoke skills such as presenting, group facilitation, or collaboration skills. But the most important is strategic thinking takes time to master.

Ellen Goldman of George Washington University has been conducting research on how executives develop strategic thinking skills. Says Goldman, “These CEOs knew they needed to upgrade their communication skills or financial acumen, but not one of them saw strategic thinking is a priority before taking the job. Person after person in my interviews said, ‘I’ve never really thought about that before.”

VUCA World Demands Better Strategic Conversations

The forces of VUCA World – technology change, social change, globalization, and more – are shooting slow-motion bullets across our economy.

Adaptive failure carries huge costs for society. Workers and their families lose their livelihoods. Communities see their vital institutions diminish. Meanwhile, our society and -policymakers struggle in vain to come to grips with “wicked” long-term challenges such as climate change, broken health care and education systems, and mounting public debt among others.

At a time when we desperately need better strategic conversations, they are hard to come by. John Seeley Brown – the bestselling author – has participated in scores of strategic conversations over the past four decades, as an executive, board member, and outside expert. Reflecting on his experiences, Brown says, “I don’t believe that organizations can succeed today without good strategic conversations – and yet it’s very seldom that I see them”

While better conversations alone cannot solve all our problems, it is hard to make real progress without them. Strategic conversations offer our best hope for flushing out and conquering the powerful yabbuts. They are a critical resource for resolving adaptive challenges.

Make It An Experience

DESIGNING STRATEGIC CONVERSATIONS AS MOMENTS OF IMPACT

You have seen how strategic conversations can help organizations resolve their toughest challenges. And you have seen how important it is to design strategic conversations rather than approach them as standard meetings. That is because successful strategies do not come from spreadsheets, slide shows or detailed agendas.

Effective strategic choices come from great conversations where people combine their best ideas in new ways. They come from people sharing moments of insight so compelling they demand action. Such moments rarely show up without help. They happen when strategic conversations are designed, following the core principles outlined by the authors . Of these principles, one looms largest.

The authors quoted Machiavelli on the hazards involved in “the introduction of a new order of things”:

Nothing is more difficult to handle, more doubtful of success, nor more dangerous to manage, than to put oneself at the head of introducing new orders. For the introducer has all those who benefit from the old order as enemies, and he has lukewarm defenders in all those who might benefit from the new orders. This lukewarmness arises partly from fear of adversaries … and partly from the incredulity of men, who do not truly believe in new things unless they have come to a firm experience of them (emphasis added by the authors).

Machiavelli realized that experience is not just the best teacher – it is the only one. When strategic conversations are designed as engaging experiences, people interact with issues in fundamentally different ways. They see them from the right distance – far enough away to have perspective yet close enough to also focus on the details that matter most. That is the space where new possibilities can take place.

Machiavelli was right. The best way to help people is to give them a visceral experience of a future possibility. That is what creates a moment of impact.

Leading Strategic Conversations That Create Hope

The yabbuts are the most common obstacle that stymie strategic conversations. The yabbuts can be difficult to overcome, but in most situations they can be navigated by following the principles and practices laid out by the authors.

Strategic conversations counteract yabbuts.

- Defining a clear purpose and engaging multiple perspectives help to neutralize bad politics.

- Giving people a visceral experience of future possibilities keeps near-termism at bay.

- Framing the issues enables better strategic thinking and more creative solutions.

In well-designed strategic conversations, the yabbuts don’t disappear. But they get starved of oxygen long enough to get important work done.

That is when you can raise your ambition and lean in harder. Because your real goal is not just to neutralize the yabbuts. It is to get people focused on creating a better future with a sense of common purpose, in an environment where creativity and collaboration can flourish.

Stepping Up To Your Next Strategic Conversation

The authors have argued that their approach to designing strategic conversation can lead to better results than standard strategy meetings. They also realize this approach is different from what people are used to and will thus feel risky to some.

Yet the comfortable standard meeting approach carries a more likely risk: that the session will have little impact. When was the last time you recall a linear-agenda, slideshow-driven meeting that drove real progress against a tough adaptive challenge?

It is unusual for people to walk away from a well-designed strategic conversation saying it was “okay.” And it’s rare for such sessions to fail. As you step up designing your next strategic conversation, here are a few a parting thoughts on how to make it as successful as possible.

- Start with a ripe issue. Effective conversations focus on issues where the timing is right, when there is a sense of urgency – but not panic – to do something, either because of a growing threat or a growing opportunity that demands attention. Don’t design a session for a topic that is too distant or too immediate in focus. These situations call for other approaches.

- Fight for the time to do it right. Tackling adaptive challenges takes time. But well-designed strategic conversations use that time efficiently. Two days of quality conversation among the right people can accomplish more than two months of unfocused effort. Do not let anyone persuade you to cram two days of work into two hours – it won’t work, and it will just frustrate you and your participants.

- Lead with empathy. The authors cannot emphasize this enough. You must take the time to understand participants’ perspectives – their points of view – long before you walk into the room. Doing so will help you design a session that truly resonates with the group.

- Put all the core principles to work. The five principles and their key practices are a package deal, not on a á la carte menu. If you have the right perspectives in the room but the issues are poorly framed, it won’t work.

- Simplify, simplify, simplify. Meeting organizers often try to cram too much material into too little time. Great design strives for simplicity, and great conversations need room to breathe. As you design your next session, resist the temptation to keep adding people in the room, topics to the agenda, and words on each slide. Find the courage to include only those elements that are essential to sparking a focused and productive strategic conversation.

- Start small, then build. If you are new to this approach, start with lower stakes and less complex situations to build your skill and confidence – then expand from there. Find small ways to try this out with a friendly group before taking it into the boardroom.

- Prep like hell – and then let go. Black belts overprepare their sessions and then expect to improvise as events unfold in the room. This may sound like a contradiction, but it’s not. People who are hyperprepared are much more comfortable and confident when they have to go off script.