By Manuel “Bobby” Orig, Director, Apo Agua

ATOMIC HABITS

An Easy & Proven Ways to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones

By James Clear

We convince ourselves that massive success requires massive action. Actually, the inverse is true: Small improvements accumulate into remarkable results.

Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement. The same way that money multiplies through compound interest, the effects of your habits multiply as you repeat them.

If you get 1% better each day, you’ll end up with results nearly 37x better after 1 year. ( 1% better every day for one year. 1.01365 = 37.78 )

The effects of small habits compound over time.

Making a choice that is 1% better or 1% worse seems insignificant in the moment, but over a lifetime these choices determine the difference between who you are and who you could be.

Praise for the book

No matter your goals, Atomic Habits offers a proven framework for improving – every day. James Clear, one of the world’s leading experts on habit formation, reveals practical strategies that will teach you exactly how to form good habits, break bad ones, and master the tiny behaviors that lead to remarkable results.

- Goodreads Choice Award nominee for best nonfiction (2018)

About the author

James Clear is a writer and speaker focused on habits, decision making, and continuous improvement. He is the author of the #1 New York Times bestseller, Atomic Habits. The book has sold 5 million copies worldwide and has been translated into more than 50 languages.

INTRODUCTION

a-tom-ic

- an extremely small amount of a thing; the single irreducible unit of a larger system.

- the source of immense energy or power.

hab-it

- a routine or practice performed regularly, an automatic response to a specific situation.

HOW THE AUTHOR LEARNED ABOUT HABITS

On the final day of his sophomore year of high school, the author was hit in the face with a baseball bat. As his classmate took a swing, the bat slipped out of his hands and came flying toward him before striking him directly right between the eyes. He had no memory of the moment of impact.

The following months were hard. It felt like everything in his life was on pause. He had double vision for weeks; he could not literally see straight. It took more than a month, but his eyeball did eventually return to its normal location. Between seizures and his vision problems, it was eight months before he could drive a car again.

He became painfully aware of how far he had to go when he returned to the baseball field one year later. Baseball had always been a major part of his life. His dad played minor league baseball for the St. Louis Cardinals, and he had a dream of playing professionally, too. After months of rehabilitation, what he wanted more than anything was to get back on the field.

But the author’s return to baseball was not smooth. When the season rolled around, he was the only junior to be cut from the varsity baseball team. He was sent down to play with the sophomores on junior varsity. For someone who had spent so much time and effort on the sport, getting cut was humiliating.

After a year of self-doubt, he managed to make the varsity team as a senior, but he rarely made it on the field.

Despite his lackluster high school career, the author still believed he could become a great player. And he knew that if things were going to improve, he was the one responsible for making it happen. The turning point came two years later after his injury, when he began college at Dennison University. It was a new beginning, and it was the place where he would discover the surprising power of small habits for the first time.

Attending Dennison University was one of the best decisions of the author’s life. He earned a spot on the baseball team and although he was at the bottom of the roster as a freshman, he was thrilled. Despite the chaos of his high school years, he had managed to become a college athlete.

While his peers stayed up late and played video games, he built good sleep habits and went to bed early each night. In the messy world of college dorm, he made it a point to keep his room neat and tidy. These improvements were minor, but they give him a sense of control over his life. He started to feel confident again. And this growing belief rippled into the classroom as he improved his study habits and managed to earn straight As during his first year.

A habit is a routine or behavior that is performed regularly – and in many cases, automatically. As each semester passed, he accumulated small but consistent habits that ultimately led to results that were unimaginable to him when he started. By the time he graduated, he was listed in the school record books in eight different categories. That same year, he was awarded the university’s highest academic honor, the President’s medal.

In stating all these facts, the author asks for forgiveness if he sounds boastful. He said, to be honest, there was nothing legendary or historic about his athletic career. He never ended up playing professionally. However, looking back on those years, he believes he has accomplished something just as rare: He fulfilled his potential. And he believes the concepts in this book can help you fulfill your potential as well.

HOW HABITS SHAPE YOUR IDENTITY

Why is it so easy to repeat bad habits and so hard to form good one? Few things can have a more powerful impact on your life than improving your daily habits. And yet it is likely that this time next year you’ll be doing the same thing rather than something better.

It often feels difficult to keep good habits going for more than a few days, even with sincere effort and the occasional burst of motivation. Habits like exercise, meditation, and cooking are reasonable for a day to two and then become a hassle.

However, once your habits are established, they seem to stick around forever – especially the unwanted ones. Despite our best intentions, unhealthy habits like eating junk food, watching too much television, procrastinating, and smoking can feel impossible to break.

Changing our habits is challenging for two reasons: (1) we try to change the wrong thing and (2) we try to change our habits in the wrong way.

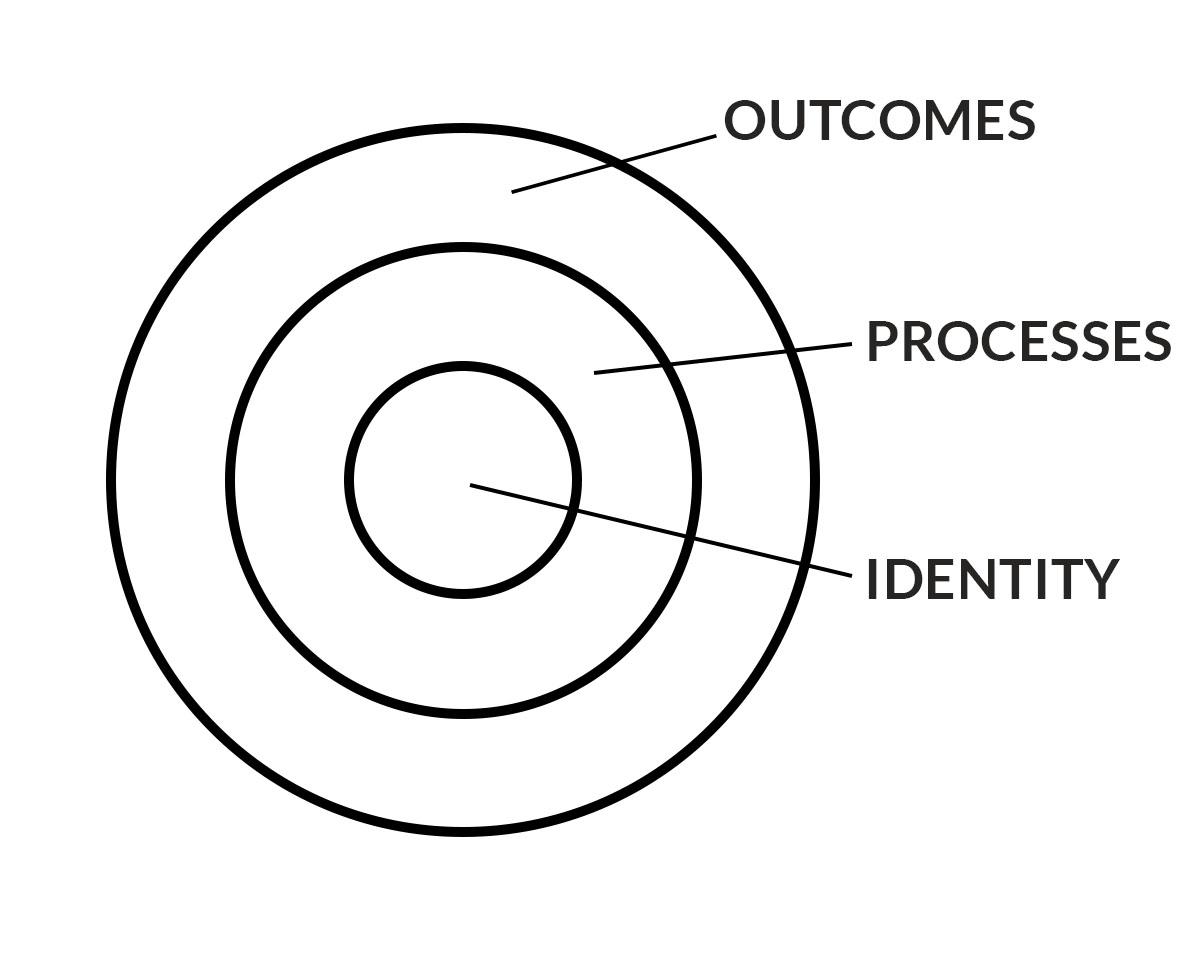

Our first mistake is that we try to change the wrong thing. To understand what the author mean, consider that there are three levels at which change can occur. You can imagine them like layers of an onion.

THREE LAYERS OF BEHAVIOR CHANGE

The first layer is changing your outcomes. This level is concerned with changing your results: losing weight, publishing a book, winning a championship. Most of the goals are associated with this level of change.

The second layer is changing your process. This level is concerned with changing your habits and systems: implementing a new routine at the gym, decluttering your desk for better workflow, developing a meditation practice. Most of the habits you build are associated with this level.

The third and deepest layer is changing your identity. This level is concerned with changing your beliefs: your worldview, your self-image, your judgments about yourself and others. Most of the beliefs, assumptions, and biases are associated with this level.

Outcomes are about what you get. Processes are about what you believe. When it comes to building habits that last, the problem is not that one level is “better” or “worse” than another. All levels of change are useful in their own way. The problem is the direction of change.

Many people begin the process of changing their habits by focusing on what they want to achieve. This leads us to outcome-based habits.

The alternative is to build identity-based habits. With this approach, we start by focusing on who we want to become.

Imagine two people resisting a cigarette. When offered a smoke, the first person says, “No thanks. I’m trying to quit.” It sounds like a reasonable response, but this person still believes they are a smoker who is trying to be something else. They are hoping their behavior will change while carrying around the same beliefs.

The second person declines by saying, “No thanks. I’m not a smoker.” It’s a small difference, but this statement signals a shift in identity. Smoking was part of their former life, not their current one. They no longer identify as someone who smokes.

Most people don’t even consider identity change when they set out to improve. They just think, “I want to be skinny (outcome) and if I stick to this diet, then I’ll be skinny (process). They set goals and determine the actions they should take to achieve those goals without considering the beliefs that drive their actions. They never shift the way they look at themselves, and they don’t realize that their old identity can sabotage their new plans for change.

Behavior that is incongruent with the self will not last. You may want more money, but if your identity is someone who consumes rather than create, then you’ll continue to be pulled toward spending rather than earning. You may want better health, but if you continue to prioritize comfort over accomplishment, you’ll be drawn to relaxing rather than training. It’s hard to change your habits if you never change the underlying beliefs that led to your past behavior. You have a new goal and a new plan, but you haven’t changed who you are.

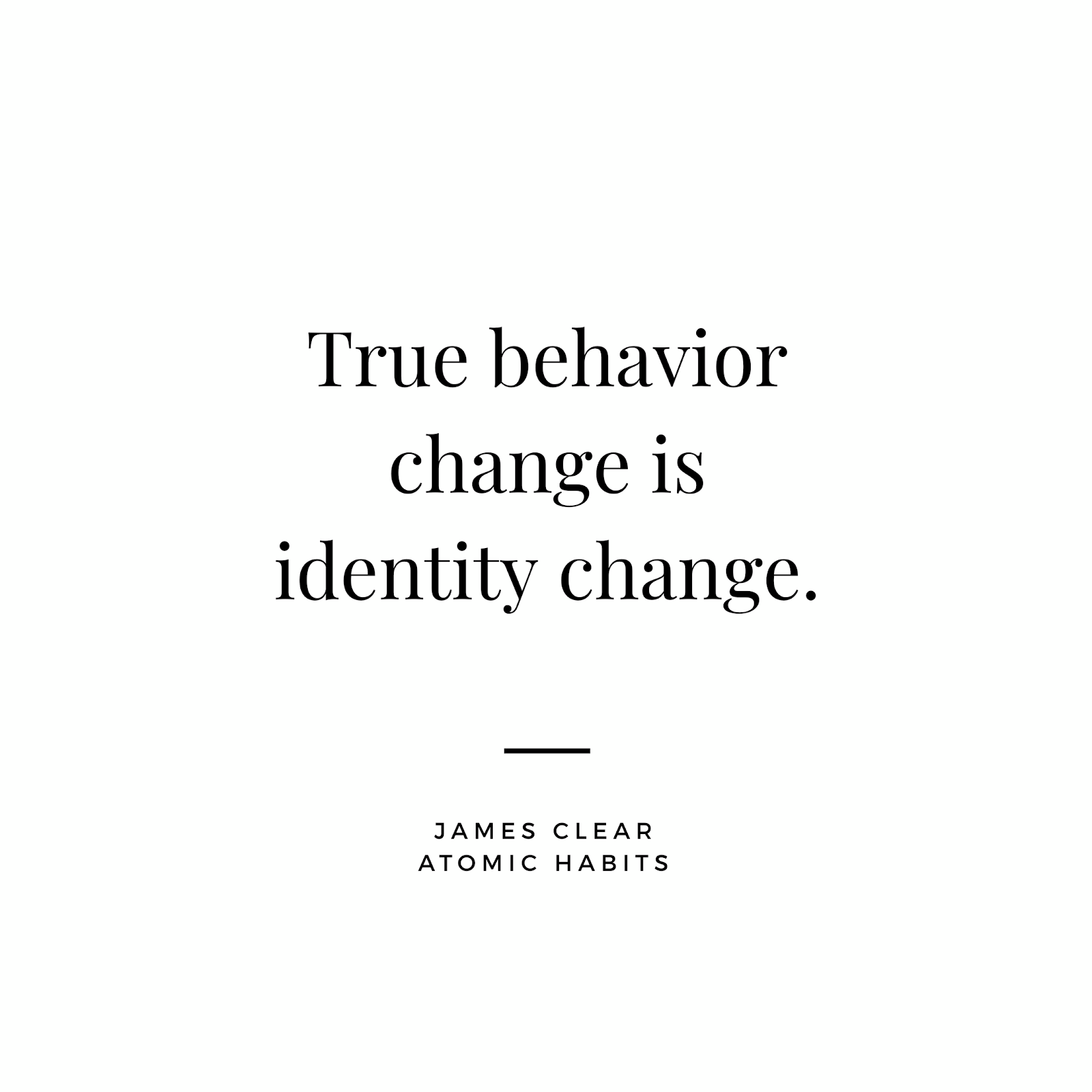

True behavior change is identity change. You might start a habit because of motivation, but the only reason you’ll stick with one is that it becomes part of your identity. Anyone can convince themselves to visit the gym or eat healthy once or twice, but if you don’t shift the belief behind the behavior, then it is hard to stick with the long-term changes. Improvements are only temporary until they become part of who you are:

- the goal is not to read a book, the goal is to become a reader.

- The goal is not to run a marathon, the goal is to become a better runner.

- The goal is not to learn an instrument, the goal is to become a musician.

Your behaviors are usually a reflection of your identity. What you do is an indication of the type of person you believe that you are – either consciously or unconsciously. Research has shown that once a person believes in a particular aspect of their identity, they are more likely to act in alignment of that belief.

THE SURPRISING POWER OF ATOMIC HABITS

The faith of British Olympic Cycling changed one day in 2003. The organization which was the governing body of professional cycling in Great Britain, had recently hired Dave Bailsford as its new performance director. At the same time, professional cyclists in Great Britain had endured nearly one hundred years of mediocrity. Since 1908, British riders had won just a single gold medal at the Olympic Games, and they had fared even worse in cycling’s biggest race, the Tour de France. In 110 years, no British cyclist had ever won the event.

In fact, the performance of British riders had been so underwhelming that one of the top bike manufacturers in Europe refused to sell bikes to the team because they were afraid that it would hurt sales if other professionals saw the Brits using their gear.

Bailsford had been hired to put British Cycling on a new trajectory. What made him different from previous coaches was his relentless commitment to a strategy that he referred to as “the aggregation of marginal gains,” which was a philosophy of searching for a tiny margin of improving in everything you do. Bailsford said, “The whole principle came from the idea that if you broke down everything you could think of that goes into riding a bike, and then improve it by 1 percent, you will get a significant increase when you put them all together.”

Bailsford and his coaches began by making small adjustments you might expect from a professional cycling team. They redesigned the bike seats to make them more comfortable and rubbed alcohol on the tires for a better grip. They asked riders to wear electrically heated overshorts to maintain ideal muscle temperature while riding and used biofeedback sensors to monitor how each athlete responded to a particular workout.

But they didn’t stop there. Brailsford and his team continued to find 1 percent improvements in overlooked and unexpected areas. They tested different types of massage gels to see which one led to the fastest muscle recovery. They hired a surgeon to teach each rider the best way to wash their hands to reduce the chances of catching a cold.

As these and hundreds of small improvements accumulated, the results came faster than anyone could have imagined.

Just five years after Brailsford took over, the British Cycling team dominated the road and track cycling events at the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, where they won an astounding 60 percent of the gold medals available. Four years later, when the Olympic Games came to London, the Brits raised the bar as they set nine Olympic records and seven world records.

That same year, Bradley Wiggins became the first British cyclist to win the Tour de France. The next year, his teammate Chris Froom won the race, and he would go on to win again in 2015, 2016, and 2017, giving the team five Tour de France victories in six years.

During the ten-year span from 2007 to 2017, British cyclists won 78 world championships and sixty six Olympic or Paralympic gold medals and capture five Tour de France victories in what is widely regarded as the most successful run in cycling history.

How does this happen? How does a team of previously ordinary athletes transform into world champions with tiny changes that, at first glance, would seem to make a modest difference at best? Why do small improvements accumulate into such remarkable results, and how can you replicate this approach in your own life?

WHY SMALL HABITS MAKE A BIG DIFFERENCE

It is so easy to overestimate the importance of one defining moment and underestimate the value of making small improvements on a daily basis. Too often, we convince ourselves that massive success requires massive action. Whether it is losing weight, building a business, writing a book, winning a championship, or achieving any other goal, we put pressure on ourselves to make some earth-shattering improvement that everyone will talk about.

Meanwhile, improving by 1 percent isn’t particularly noticeable – but it can be far more meaningful, especially in the long run. The difference of tiny improvement can make over time is astounding.

Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement. The same way that money multiplies through compound interest, the effects of your habits multiply as you repeat them. They seem to make little difference on any given day and yet the impact they deliver over the months and years can be enormous. It is only when looking back two, five, or perhaps ten years later that the value of good habits and the cost of bad ones become strikingly apparent.

This can be a difficult concept in daily life. We often dismiss small changes because they don’t seem to matter very much in the moment. If you save a little money now, you’re still not a millionaire. If you go to the gym three days in a row, you’re still out of shape. We make a few changes but the results never seem to come quickly and so we slide back into our previous routines.

Unfortunately, the slow pace of transformation also makes it easy to let a bad habit slide. If you eat an unhealthy meal today, the scale doesn’t move much. If you procrastinate and put your project off until tomorrow, there will be usually time to finish it later. A single decision is easy to dismiss.

But when we repeat 1 percent errors, day after day, by replicating poor decisions, duplicating tiny mistakes, and rationalizing little excuses, our small choices compound into toxic results. It’s the accumulation of many missteps – a 1 percent decline here and there – that eventually leads to a problem.

It doesn’t matter how successful or unsuccessful you are right now. What matters is whether your habits are putting you on the path toward success. You should be far more concerned with your current trajectory than with your current results. If you’re a millionaire but you spend more than you earn each month, then you’re on a bad trajectory. If your spending habits don’t change, it’s not going to end well. Conversely, if you’re broke, but you save a little bit every month, then you’re on the path toward financial freedom – even if you’re moving slower than you like.

Your outcomes is a lagging measure of your habits. Your net worth is a lagging measure of your financial habits. Your weight is a lagging measure of your eating habits.

Time magnifies the margin between success and failure. It will multiply whatever you feed it. Good habits make time your ally. Bad habits make time your enemy.

Habits are a double-edged sword. Bad habits can cut you down just as easily as good habits can build you up, which is why understanding the details is crucial. You need to know how habits work and how to design them to your liking, so you can avoid the dangerous half of the blade.

FORGET ABOUT GOALS, FOCUS ON SYSTEMS INSTEAD

Prevailing wisdom claims that the best way to achieve what we want in life – getting into better shape, building a successful business, relaxing more and worrying less, spending more time with friends and family – is to set specific, actionable goals.

For many years, this is how the author approached his habits, too. Each one was a goal to be reached. He set goals for the grades he wanted to get in school, for the weights he wanted to lift in the gym, for the profits he wanted to earn in business. He succeeded at a few, but he eventually failed at a lot of them. Eventually, he began to realize that his results had very little to do with the goals he set and nearly everything had to do with the systems he followed.

What’s the difference between systems and goals? It’s a distinction that the author first learned from Scott Adams, the cartoonist behind the Dilbert comic. Goals are about the results you want to achieve. Systems are about the processes that lead to those results.

- If you’re a coach, your goal might be to win a championship. Your system is the way you recruit players, manage your assistant coaches, and conduct practice.

- If you’re an entrepreneur, your goal might be to build a multi-million dollar business. Your systems is how you test the product ideas, hire employees, and run marketing campaigns.

- If you’re a musician, your goal might be to play a new piece. Your system is how often you practice, how you break down and tackle difficult measures, and your method of receiving feedback from your instructor.

Now for the interesting question: If you completely ignored your goals and focused only on your system, would you still succeed? For example, if you were a basketball coach and you ignored your goal to win a championship and focused only on what your team does in practice each day, would you still get results?

The author believes you would.

The goal in any sport is to finish with the best score, but it would be ridiculous to spend the whole game staring at the scoreboard. The only way to win is to get better each day. The same is true for other areas of your life. If you want better results, then forget about setting goals. Focus on your system instead.

Are goals completely useless? Of course not. Goals are good for setting direction, but systems are best for making progress.

THE BEST WAY TO START A NEW HABIT

In 2001, researchers in Great Britain began working with 248 people to build better exercise habits over the course of two weeks.

The first group was the control group. They were simply asked to track how often they exercised.

The second group was the “motivation” group. They were asked not only to track their workouts but also to read some material on the benefits of exercise. The researchers also explained to the group how exercise could reduce the risk of coronary disease and improve your health.

Finally, there was the third group. These subjects received the same presentation as the second group, which ensured that they had equal levels of motivation. However, they were also asked to formulate a plan for when and where they would exercise over the following week. Specifically, each member of the third group completed the following sentence: “During the next week, I will partake in at least 20 minutes of vigorous exercise on [DAY] at [TIME] in [PLACE].

In the first and second groups, 35 to 38 percent of the people exercised at least once per week. (Interestingly, the motivational presentation given to the second group seemed to have NO meaningful impact on behavior). But 91 percent of the third group exercised at least once per week – more than double the normal rate.

The sentence they filled out is what researchers refer to as an implementation intention, which is a plan you make beforehand about when and where to act. That is how you intend to implement a particular habit.

The cues that can trigger a habit comes in a wide range of forms – but the two most common cues are time and location. Implementation intentions leverage these cues:

Broadly speaking, the format for creating

an implementation is this:

“When situation X arises, I will perform

Response Y.”

Hundreds of studies have shown that implementation intentions are effective for sticking to our goals, whether it’s writing the exact time and date of when you will get a flu shot or recording the time of your colonoscopy appointment. They increase the odds that people will stick with habits.

The punch line here is clear: people make a specific plan for when and where they will perform a new habit are more likely to follow through. Too many people try to change their habits without these basic details figured out. We tell ourselves, “I’m going to eat healthier” or “I’m going to write more,” but we never say when and where these habits are going to happen. We leave it up to chance and hope that we will “just remember to do it” or feel motivated at the right time.

Many people think they lack motivation when what they really lack is clarity. It is not always obvious when and where to take action. Some people spend their entire lives waiting for the right time to make an improvement.

Once an implementation intention has been set, you don’t have to wait for inspiration to strike. Do I write a chapter today or not? Do I meditate this morning or at lunch? When the moment of action occurs, there is no need to make a decision. Simply follow your predetermined plan.

The simple way to apply this strategy

to your habits is to fill out this sentence:

I will [BEHAVIOR] at [TIME] in [LOCATION].

MOTIVATION IS OVERRATED;

ENVIRONMENT OFTEN MATTERS MORE

Anne Thorndike, a primary care specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital, had a crazy idea. She believed she could improve the eating habits of thousands of hospital staff and visitors without changing their willpower or motivation in the slightest way.

Thorndike and her colleagues designed a six-month study to alter the “choice architecture” of the hospital cafeteria. They started by changing how drinks were arranged in the room. Originally, the refrigerators located next to the cash registers in the cafeteria were filled with only soda. The researchers added water as an option to each one. Additionally, they placed baskets of water next to the food stations throughout the room. Soda was still in the primary refrigerators, but water was now available at all drink locations.

Over the next three months, the number of soda sales at the hospital dropped by 11.4 percent. Meanwhile, sales of bottled water increased by 25.8 percent. They made similar adjustments and saw similar results. Nobody had said a word to anyone eating there.

People often choose products not because of what they are, but because of where they are. Your habits change depending on the room you are in and the cues in front of you.

Environment is the invisible hand that shapes human behavior. Despite our unique personalities, certain behaviors tend to rise again and again under certain environmental conditions. In church, people tend to talk in whispers. On a dark street, people act wary and guarded. In this way, the most common form of change is not internal, but external: we are changed by the world around us. Every habit is context dependent.

THE TRUTH ABOUT TALENT

(When Genes Matter and When They Don’t)

Many people are familiar with Michael Phelps, who is widely considered to be one of the greatest athletes in history. Phelps had won more Olympic medals not only than any swimmer but also more than any Olympian in any sport.

Fewer people know the name Hicham El Guerrouj, but he was a fantastic athlete in his own right. El Guerrouj is a Moroccan runner who holds two Olympic gold medals and is one of the greatest middle-distance runners of all time. For many years, he held the world record in the mile, 1,500-meter, and 2,000-meter races. At the Olympic Games in Greece in 2004, he won the gold medal in the 1,500-meter and 500-meter races.

These two athletes are wildly different in many ways. For starter, one competed on land and the other on water. But most notably, they differ significantly in height. El Gerrouj is five feet, nine inches tall. Phelps is six feet, four inches tall. Despite this seven inch difference in height, the two men were identical in one respect: Michael Phelps and El Gerrouj wear the same length of inseam on their pants.

How is this possible? Phelps has relatively short legs for his height and a very long torso, the perfect build for swimming. El Gerrouj has incredibly long legs and a short upper body, an ideal frame for distance running.

Now imagine if these world-class athletes were to switch sports. Given his remarkable athleticism, could Michael Phelps become an Olympic caliber distance runner with enough training? It’s unlikely. At peak fitness, Phelps weighed 194 pounds, which is 40 percent heavier than El Gerrouj, who competed at an ultra light 138 pounds. Taller runners are heavier runners, and every extra pound is a curse when it comes to distance running. Against elite competition, Phelps would be doomed from the start.

Similarly, El Gerrouj might one of the best distance runners in history, but it’s doubtful he would ever qualify for the Olympics as a swimmer. Since 1976, the average height of Olympic gold medalists in the mens’s 1,500-meter run is five feet, ten inches. In comparison, the average height of Olympic gold medalists in the men’s100-meter freestyle swim is six feet, four inches tall and have long backs and arms, which are ideal for pulling through the water. El Gerrouj would be at a severe disadvantage.

The secret to maximizing your odds of success is to choose the right field of competition. The is just as true with habit change as it is with sports and business. Habits are easier to perform, and more satisfying to stick with, when they align with your natural inclinations and abilities. Like Phelps on the pool, and El Gerrouj on track, you want to play a game where the odds are in your favor.

HOW YOUR PERSONALITY INFLUENCES YOUR HABITS

Your genes are operating beneath the surface of every habit. Indeed, beneath the surface of every behavior. Genes have been shown to influence everything from the number of hours you spend watching television to your likelihood to marry or divorce, to your tendency to get addicted to drugs, alcohol, or nicotine. There’s a strong genetic component to how obedient or rebellious you are when facing authority, how vulnerable or resistant you are to stressful events, how proactive or reactive you tend to be, and even how captivated or bored you feel during sensory experiences like attending a concert.

Bundled together, your unique cluster of genetic traits predispose you to a particular personality. Your personality is the set of characteristics that is consistent from situation to situation. The most proven scientific analysis of personality traits is known as the “Big Five,” which breaks them down into five spectrums of behavior:

- Openness to experience: from curious and inventive on one end to cautious and consistent on the other.

- Conscientiousness: organized and efficient to easygoing and spontaneous.

- Extroversion: outgoing and energetic to solitary and reserved (you likely know them as extroverts vs. introverts).

- Agreeableness: friendly and compassionate to challenging and detached.

- Neuroticism: anxious and sensitive to confident, calm, and stable.

Our habits are not solely determined by our personalities, but there is no doubt that our genes nudge us in a certain direction. Our deeply rooted preferences make certain behaviors easier for some people than for others.

The takeaway is that you should build habits that work for your personality. People can get ripped working out like a bodybuilder, but if you prefer rock climbing or cycling, or rowing, then shape your exercise habit around your interests. If you want to read more, don’t be embarrassed if you prefer steamy romance novels over nonfiction. Read whatever fascinates you. Choose the habit that best suits you, not the one that is most popular.

There is a version of every habit that can bring you joy and satisfaction. Find it. habits need to be enjoyable if they are going to stick.

CONCLUSION

THE SECRET TO RESULTS THAT LAST

There is an ancient Greek parable known as the Sorites Paradox, which talks about the effect one small action can have when repeated enough times. One formulation of the paradox goes as follows: Can one coin make a person rich? If you give a person a pile of ten coins, you wouldn’t claim he or she is rich. But if you add another? And another? And another? At some point, you will have to admit that no one can be rich unless once coin make him or her so.

We can say the same about atomic habits. Can one tiny change transform your life? It’s unlikely you would say so. But if you made another? And another? And another? At some point, you will have to admit that your life was transformed by one small change.

The holy grail of habit change is not a single 1 percent improvement, but a thousand of them. It’s a bunch of atomic habits stacking up, each one a fundamental unit of the overall system.

In the beginning, the small improvements can often seem meaningless because they get washed away by the weight of the system. Just one coin won’t make you rich, one positive change like meditating for one minute or reading one page each day is unlikely to deliver a noticeable difference.

Gradually, though, as you continue to layer small changes on top of one another, the scales of life start to move. Each improvement is like adding a grain of sand to the positive side of the scale, slowly tilting things in your favor. Eventually, if you stick with it, you hit a tipping point. Suddenly, it feels easier to stick with good habits. The weight of the system is working for you rather than against you.

Success is not a goal to reach or a finish line to cross. It is a system to improve, an endless process to refine. If you’re having trouble changing your habits, the problem isn’t you. The problem is your system. Bad habits repeat themselves again and again not because you don’t want to change, but because you have the wrong system for change.

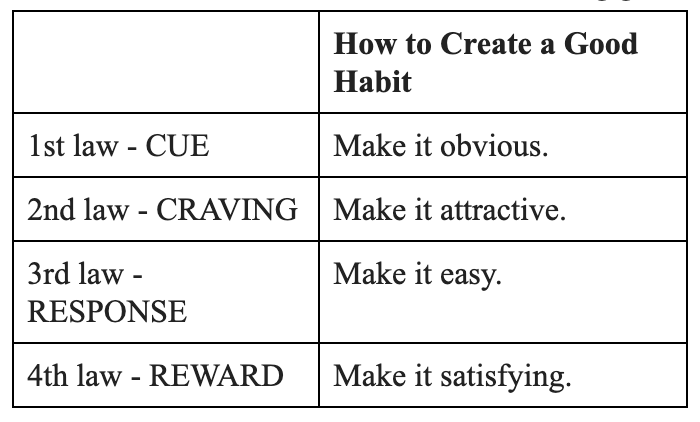

With the Four Laws of Behavior, you have a set of tools and strategies that you can use to build better systems and shape better habits.

- Sometimes a habit will be hard to remember and you’ll need to make it obvious.

- Other times you won’t feel like starting and you’ll need to make it attractive.

- In many cases, you will find that a habit will be too difficult and you’ll need to make it easy.

- And sometimes, you won’t feel like sticking with it and you’ll need to make it satisfying.

This is a continuous process. There is no finish line. There is no permanent solution. Whenever you’re looking to improve, you can rotate the Four Laws of Behavioral Change until you find the next bottleneck. Make it obvious. Make it attractive. Make it easy. Make it satisfying. Round and round. Always looking for the next way to get 1 percent better.

The secret to getting results that last is to never stop making improvements. It’s remarkable what you can build if you just don’t stop. It’s remarkable the business you can build if you don’t stop working. It’s remarkable the body you can build if you don’t stop training. It’s remarkable the fortune you can build if you don’t stop saving. It’s remarkable the friendships you can build if you don’t stop caring. Small habits don’t add up. They compound.

That’s the power of atomic habits. Tiny changes. Remarkable results.

/// end

University of Experience is a special Aboitiz Eyes section that focuses on leadership insights from the unique experiences, perspectives, and wisdom of leaders who have stood at the helm of Aboitiz over the years.

If you enjoyed this article, would like to suggest a topic, or simply share your feedback, please CLICK HERE.