By Manuel “Bobby” Orig, Consultant, Apo Agua

DELIBERATE CALM

How To Learn And Lead In A Volatile World

By Jacqueline Brassey, Aaron De Smet, Michiel Kruyt

As change accelerates daily in our increasingly complex world, leaders tasked with performing outside their comfort zones in both their personal and professional lives must adapt. Yet the same conditions that make it so important to adapt may also trigger fear, causing resistance to change and a default to reactive behavior. The authors call this the “adaptability paradox”: at a time when we most need to learn and grow, we stick with what we know, often in ways that stifle change and motivation. To avoid this trap and be ahead of the curve, leaders must become proactive.

Enter Deliberate Calm, which combines cutting-edge neuroscience, psychology, and consciousness practices along with the authors’ decades of experience with leaders around the globe. By practicing Dual Awareness, which integrates internal and external experiences, leaders can become resilient and respond to challenges with intentional choice instead of being limited to old models of success. With Delibarate Calm, anyone can lead and learn with awareness and choice to realize their full potential, even in times of uncertainty, complexity, and change.

Praise for the book

“A must-read for anyone looking to gain confidence to face the challenges in life.”

—ARIAN HUFFTINGTON, founder and CEO of Thrive Global

“When faced with a situation we have never encountered before, it is natural for most of us to panic … But deliberately facing this unknown will improve one’s adaptability, learning agility, and overall awareness.”

—W. WARREN BURKE, PhD, professor emeritus of psychology and education, Columbia University

About the authors

JACQUELINE BRASSEY, PhD, is McKinsey’s chief scientist, the director of research science for People and Organizational Performance at McKinsey, and a global leader with the McKinsey Health Institute. She is also affiliated with the Vrije Univeriteit Amsterdam in the Netherlands, is an adjunct professor at IE University in Madrid, Spain, and serves on the supervisory board of Save the Children NL.

AARON DE SMET is a senior partner at McKinsey & Company. For twenty-five years, he has helped institutions transform to improve performance and organizational health. After getting his MBA in 1992, Aaron helped lead research to enhance the impact of behavioral psychology at Columbia University, and joined McKinsey in 2003.

MICHIEL KRUYT is the CEO of Imagine.one with a mission of helping business leaders create systemic transformation toward a more sustainable and equal planet. Before joining Imagine, Michiel was a partner at McKinsey & Company and a cofounder and managing partner of change leadership at the firm Aberkyn. He started his career working for Unilever in the Netherlands, Italy, and the U.S. He is a board member of the Urban Consciousness Center in Amsterdam.

INTRODUCTION

Leaders are more powerful role models when they learn than when they teach.

—Rosabeth Moss Kanter

In 2009, Captain Chesley Sullenberger illustrated what it means to practice Deliberate Calm in the midst of a crisis. When a bird strike cut both engines of his commercial flight soon after takeoff, he was facing the unknown, and the stakes could not have been higher. But he did not panic and, perhaps even more important, he did not rely on a standard playbook or protocol to give him a false sense of security. Instead, he recognized the situation he was in, mastered his internal response, and made the difficult yet necessary decision to reject the advice from air traffic control to return to the airport and to instead land the plane in the Hudson River.

This is Deliberate Calm in action.

Miracle on the Hudson. #OTD in 2009, US Airways Flight 1549 made an emergency landing in the Hudson River after a flock of birds struck and disabled the engines of the Airbus 320 moments after takeoff. Everyone on board survived. pic.twitter.com/27B6IJX01m

— National Air and Space Museum (@airandspace) January 15, 2022

As leaders, this may seem at face value like an unrelatable scenario. Most of us are not flying planes, nor do we have hundreds of lives in our hands. But more and more, we are tasked with the difficult job of balancing with a rational and deliberate thought process in the midst of chaos and uncertainty, if not an actual crisis. When we are able to do this, we can catch early internal signals of distress, doubt, or fear without acting out a response that often makes the situation even worse. For a leader facing a complex business challenge, this can be the difference between adapting as needed to rise to the occasion and failing to adapt, missing opportunities to innovate, or worse. For Captain Sullenberger, it was the difference between life and death.

Deliberate Calm is not only a book about a new or better style of leadership. The problem with claiming that one type of leadership behavior is more effective than another is that different styles are better suited to certain situations. But most leaders select their styles based largely on personal preference, on the latest fad, or worse, unconsciously, on ingrained patterns and habits. What we need, instead, is the ability and tools to thoughtfully address the situation and select the behavior that is best suited to our particular challenge or opportunity. This ability is becoming increasingly important, particularly when we need to learn and adapt. As the world has become more turbulent and volatile, adaptability has emerged as the number one critical capability for leaders.

However, it is difficult to adapt, and it is even more difficult precisely when it matters most. Adaptability, learning, innovation, and creativity are most challenging in high-stakes, uncertain situations – exactly when they are most needed. The human brain is wired to react to these situations with the exact opposite of learning and creativity, and this threatens to undermine our performance in the most critical moments.

Deliberate Calm is the solution. It is not a leadership style or behavior. Rather, it’s a personal self-mastery practice that provides leaders with the awareness and skills to avoid reacting ineffectively and to instead choose the mode of thinking and acting that is most effective on their current circumstances.

At its core, Deliberate Calm is a unique combination of four sets of skills applied to the context of leaders: adaptability, learning agility, awareness, and emotional self-regulation. Each of these skills is critical to the success and performance of leaders, but this is the first time they have been combined to help us learn and lead differently when it matters most.

Practicing Deliberate Calm is more important than ever. Our world is changing rapidly, forcing us to deal with unprecedented levels of uncertainty and volatility, both individually and collectively. More and more, we are tasked with making high-stakes decisions when our old methods and success models are not fit for the new challenge we are facing. Often, we don’t know what will work or if a solution will ever be discovered, just as Captain Sullenberger could not have known whether or not his radical plan to land in the Hudson River would succeed.

This unfamiliar context is what we call the Adaptive Zone. In order to succeed in this zone, we must adapt, break free of our established patterns and habits, open our minds, learn new things, and even find new ways of learning and collaborating. In the Adaptive Zone, there is tremendous opportunity for creativity, growth, innovation, and true transformation, but there is also risk of failure and stagnation if we fail to learn and change. It all depends on how well we navigate this zone and if we avoid the natural tendencies that are likely to keep us stuck.

The ability to recognize when the challenges you are facing are in the Adaptive Zone and to use it as an opportunity to learn and grow instead of reacting to outdated and ineffective patterns lies at the heart of Deliberate Calm.

We are biologically wired this way. Deliberate because the practices will make you aware that you have a choice in how you experience a situation and respond; and Calm because it will enable you to stay focused and present under pressure and amid volatility without being swept by your instinctive reactions.

WHY DELIBERATE CALM MATTERS

No pessimist ever discovered the secrets of the stars, or sailed to an unchartered land, or opened a new haven to the human spirit.

—Hellen Keller

Jeff is the head of sales of a lighting company. He has a good relationship with his boss, Janice, who is the owner of the company, but she puts a lot of pressure on him to deliver. A hard-driving, charismatic people person who is determined to succeed, Jeff has been with the company for a long time, and he knows that Janice relies on him as her “second-in-command.” He takes that responsibility seriously. No matter what is going on externally or internally within the firm, Jeff knows that his job is to sell. Period, no matter what.

So when changes in the industry start to negatively impact the business, Jeff gets pretty stressed. Their company relies on imports from China, and the combination of manufacturing shutdowns overseas and shipping issues has thrown their production timeline into chaos. On top of that, competing companies have began offering technologically-advanced lighting systems that have quickly come to dominate the market. It seems like everything is changing all at once, and they simply can’t keep up.

The company is in real trouble when Janice calls Jeff into her office. “We’re way off on our targets again this quarter,” she tells Jeff. Of course, this isn’t news to him. He was up all night before this meeting worrying about their sales volume and what Janice would say. “How are we going to get these numbers to where they need to be?”

This is a pivotal moment for Jeff. Janice’s question was a good one: “How are we going to get these numbers to where they need to be?” Jeff could have responded to this question in many different ways: by offering new solutions, by brainstorming with his boss, by saying he would brainstorm them with his team and get back to Janice later, or by responding honestly, “I don’t know.” Jeff didn’t do any of these things. Instead, he reverted to the old pattern of behavior that has served him well up until this point – to feel pressure, take it on his shoulders, and promise to fix it.

Jeff is breathing rapidly. His inner voice is screaming, “I don’t know!” He desperately wants to leave the room and avoid this conversation completely, and instead focus on fixing the problem rather than explaining things he doesn’t yet have an answer for, and deep down he knows that there are no easy answers. But Jeff feels Janice is counting on him and that he can’t let her down. “I’ve got this,” he tells her with determination in his voice. “I’m gathering my team now and will let them know that they have to deliver. Don’t worry, I’ll fix it.”

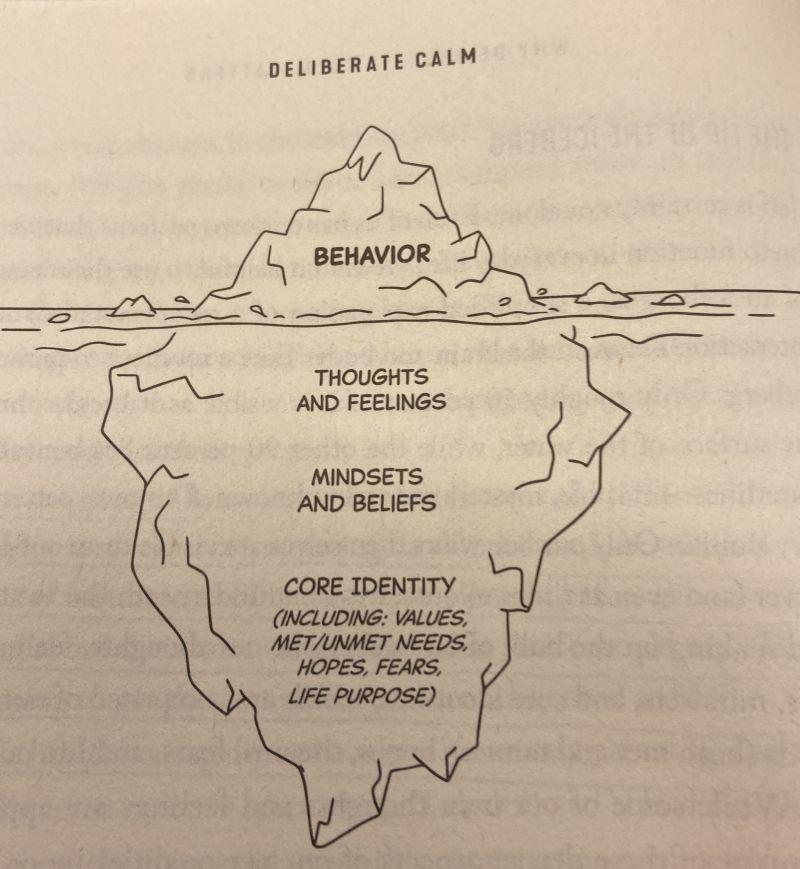

THE TIP OF THE ICEBERG

Jeff is certainly not alone. Each of us has our own patterns that we rely on to function in everyday life. We find it helpful to use the metaphor of an iceberg as a simplified explanation of a complex and dynamic interaction between the brain and the body. Take a moment to picture an iceberg. Only roughly 10 percent of it is visible as it breaks through the surface of the water, while the other 90 percent lies beneath the waterline – invisible, mysterious, and unknown. Our own patterns are very similar. Only our behaviors themselves are visible to an outside observer (and even to ourselves), but underneath the “waterline” and making up the bulk of our iceberg lie our thoughts, feelings, beliefs, mindsets, and core identities, which are comprised of our values, needs (both met and unmet), hopes, dreams, fears, and life purpose.

While some of our thoughts and feelings are apparent to us, many of these deeper aspects of our personalities lie only partly within our conscious awareness, with some elements completely obscured to even us. Yet, whether or not we are aware of it, these deeper largely unconscious layers are constantly driving our visible behaviors. Our hidden iceberg below the metaphorical water is at the root of our ongoing patterns of behaviors and actions, our decisions, and how we navigate the world throughout our lives.

If we want to navigate life better, become more likely to deliver desired results, shift unhelpful or ineffective patterns, and/or achieve our goals and aspirations, we must become aware of what is lying beneath the waterline, and address and often transform our hidden icebergs. We can only do this by diving beneath the surface and taking a clear and honest inquiry into these layers and where they come from.

Our existing iceberg patterns may not always be the best fit for our goals and aspirations, but they are not in any way “wrong” or “bad.” In fact, they serve an important function. In a complex world, they help us effectively live our lives. Instead of analyzing every situation before deciding to act, the habits buried within our icebergs allow us to take shortcuts and simplify decision-making. When facing familiar circumstances and challenges we have already mastered, these patterns often serve us well. For instance, Jeff has done very well for himself and for the company with his success model of taking ownership of problems, pushing his team, and demanding results.

The problem is that Jeff has not experienced or mastered his current challenge before, and relying on his habitual behaviors prevents him from attending to his novel challenge with an open mind and potentially a new response. Indeed, the very habits that help us operate more efficiently can also hold us back when they keep us from consciously choosing the most effective behavior in any given moment. Jeff’s habit of saying, “Don’t worry, I got this, I will fix it” is likely not a helpful approach in his current situation.

Jeff does not know how to increase sales amid the changes that are taking place in his industry, and now he has possibly made things worse for himself by making promises that he cannot keep. The success model that has worked so well for Jeff until now is no longer working, exactly at the crucial moment when he needs to perform at his best.

When facing stress, pressure, uncertainty, and/or complexity, we often feel threatened and act to protect ourselves and our core identities at the root of our icebergs. Along the way, we are apt to lose access to the parts of our brains that help us to think creatively, collaborate productively, and discover new ways of doing things. We close our minds, move to tunnel vision, and blame others or circumstances for our problems. In this fearful, threatened state, our natural tendency is to seek the comfort and familiarity of those well-established habits, and we become unable to open our minds to new ideas. This can lead to serious unintended consequences when our circumstances require us to adapt in order to come up with new solutions.

We call this the paradox of adaptability, and it is the ultimate irony for those who aspire to high levels of performance. At the very moment when we most need to break free from our habitual patterns and creatively engage with an unfamiliar, complex, or uncertain situation and choose a new and innovative response, it is that very unfamiliarity, complexity, and lack of certainty that render us unable to do so.

But what if, instead, we had the ability to open our minds at these critical moments instead of shutting down? What if we could respond with the curiosity, creativity, and collaboration that novel circumstances require? This is exactly what we gain from Deliberate Calm: Deliberate because it builds our awareness of both the external environment in which we are operating and our inner environment (out thoughts, feelings, mindsets, and beliefs) and how they impact each other, allowing us to act with a more neutral, objective situational awareness; Calm because with that awareness, we can pause under pressure and intentionally choose how to best respond and engage without being swept away by our emotions and reverting to habitual patterns of behavior.

The man who can calm his Mind when issues arise, is the Man who can conquer the world.

DUAL AWARENESS

Don’t we all wish we could have our own “sliding doors moment” when we go back and see how our lives might have been different if we had changed course at one pivotal moment? Let’s see how the outcome might have been different for Jeff, his company, and his team if he had approached the problems they were facing while practicing Deliberate Calm.

Jeff2 (as we’ll call him) and his situation start off the exact same way. The company is suffering due to rapid industry changes, and Jeff2 is feeling intense pressure. Janice calls him into her office and asks, “How are we going to get our numbers to where they need to be?”

This time, instead of reacting right away with his default answer, Jeff2 takes a breath and for just a few seconds scans his body, thoughts, feelings, and emotions. It is as if a part of him is looking down from a giant skylight in the ceiling, observing himself. As objectively and nonjudgmentally as possible, he monitors his inner world – his physical sensations, his emotions, his thoughts – without identifying with them.

In simple terms, we think of this as being detached from our feelings and thoughts rather than attached. When we are attached, there is only one “us,” and we identify with our feelings and thoughts.

When we are detached from our feelings and thoughts, however, we can observe ourselves having an experience and we can observe our feelings and thoughts. We still feel emotions, and we still may think negative or hurtful thoughts, but we can notice and accept our thoughts without fully identifying with them. In this state, we have feelings of failure instead of being a failure. We have feelings of anger instead of being angry. As long as there is a part of ourselves that remains a separate observer, we are in a position to choose a response instead of fully identifying with and getting swept away by our emotions and reacting out of habit.

The first step to detaching from our feelings and thoughts is to practice Dual Awareness, or the integrated awareness of both our external and internal environments and how they impact each other. With this awareness, we are able to access a state in which we can act with intention and perform at our best no matter what is going on around us. The ability to do this in the midst of changing, complex circumstances is the first step toward mastery in leadership, athletics, and other human endeavor.

Jeff2 is well practiced in Dual Awareness. He recognizes that the challenges he is facing require something other than his typical leadership behavior. Unlike Jeff1, Jeff 2 has the skills to buy time before giving Janice a definitive answer that he might regret later. “Let me get back to you,” he says to Janice. “There are multiple changes taking place right now and we don’t have a handle on it yet. I can’t promise that we’ll deliver on these targets, but I will come back with some ideas.”

Jeff2 take a moment to absorb Janice’s disappointed expression. “I imagine that you’re feeling anxious, and I am, too,” he tells her. “There are a lot of things going on that we’ve never faced before. But I’m confident that with my team we can identify the biggest challenges to address and come up with some solutions that will move us in the right direction.”

This is Deliberate Calm in action. It keeps Jeff2 from being swept away by emotion, helps him realize that the changes in his environment most likely require a novel approach, and gives him the simple yet profound choice to try something new.

Jeff1 is unaware and attached to his thoughts and feelings, while Jeff2 practices dual awareness and can observe himself from a distance while remaining detached. In this state, he is able to see things as they truly are and recognize that his usual way of doing things will not solve this particular challenge. Only then can he apply tools to change the course of action.

This is a key skill for leaders: to read the external reality as objectively as possible, relate it to how we feel, reflect on the decisions that need to be made, and choose how best to respond and engage. We might be triggered to push our uncomfortable emotions under the surface, drowning them in our subconscious, but proactively facing our uncomfortable emotions head-on without reacting to them is necessary if we want to evolve and grow as humans and leaders.

This is incredibly important. As we saw with Jeff1, a leader who is feeling threatened can create the same feelings in everyone around them, leading to a total breakdown in collaboration and communication. By remaining open, Jeff2 engenders the same thing in his team. Instead of leaving that meeting feeling demoralized, helpless and pressured, they feel empowered and confident that they are working to create a better future for the company. This makes them eager to work together to find solutions instead of falling into a destructive pattern of attack and defend.

At the end of the year, Jeff2’s company has sped up their innovation cycle, they’ve acquired a small tech-savvy company, and the team is empowered and able to adapt. They are still facing challenges, and there are certainly still moments when Jeff2 feels anxious and incapable, shifts into autopilot, and loses his ability to respond in the way he had intended. The problems that he is dealing with are complex, and at times Jeff2 gets overwhelmed and carried away by his strong emotions. Like all of us, Jeff2 is human and imperfect. But more and more, he is able to practice Dual Awareness, stay fluid, and make choices that he feels are best for him, the company, and his team, even during the most challenging moments.

THE FAMILIAR ZONE AND THE ADAPTIVE ZONE

As we face situations throughout our lives, we oscillate between different contextual “zones.” Broadly speaking, we find it helpful to group these into two main zones: the Familiar Zone and the Adaptive Zone. What is required of us in order to successfully navigate and thrive in each zone is markedly different.

The Familiar Zone is exactly as it sounds – an external environment that is familiar and known. We are typically well prepared for the tasks and challenges that we face in this zone. We know the landscape and the “rules of the game,” we have built up a repertoire of responses, approaches, and behaviors that are appropriate for the situation, and we more or less know what we need to do in order to succeed.

The Adaptive Zone, however, is an external environment that is new territory or “unchartered waters.” Our context is unfamiliar, uncertain, or unpredictable in some important way. Once we find ourselves in this zone, the patterns, methods, and solutions that have worked for us in the past will likely be insufficient and in order to succeed we must learn something new. Here, we don’t know what it will take to achieve a good outcome or whether or not we are up to the task.

The primary focus of Deliberate Calm is learning to identify when we enter the Adaptive Zone and how to best navigate it so we can choose the most effective response instead of reverting to old patterns or getting swept away by our emotions. This is the first half of Dual Awareness: recognizing what zone we are in and what the situation requires of us in that particular moment in order to achieve our goals and aspirations.

We have a lot to lose if we lose this awareness, are slow to realize that we are operating in the Adaptive Zone, and continue to rely on habits and patterns that are simply not fit for our current circumstances. On the other hand, when we learn to navigate this zone with greater ease, there is tremendous opportunity in the Adaptive Zone for discovery, innovation, and true transformation.

As the world becomes increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA), we are finding ourselves in the Adaptive Zone more and more frequently, facing new, never-before-seen challenges without an established toolkit to rely on. It is more important than ever for us to learn to successfully navigate the Adaptive Zone. The constant introduction of disruptive technology, the rapid democratization of information, an increased demand and competition for new talent, and the changing needs of stakeholders, among other current challenges, all demand swift changes and new, innovative solutions from both organizations and individuals. In this context, continuing to rely on our old playbooks can lead to disastrous results, while taking the opportunity to create new ones can open up space for personal and organizational growth.

PURPOSE

If you want to build a ship, don’t herd people together to collect wood and assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.

—Antoine De Saint-Exupéry

It was late in the evening, and Daniel, a senior executive at a nutritional foods company, sat in a conference room as a consultant named Kimberly challenged his mindset about leadership. “Why do they need to agree with you?” Kimberly asked him. “Why do you need to know the answer?”

Inside, Daniel was feeling incredibly irritated. He was thinking, Why can’t she see my point? He simply wanted to find a solution and solve his current problem. Why was that so difficult for her to understand?

Kimberly did understand where he was coming from and saw that he was stuck. Daniel had built his whole career operating from a strong set of beliefs about how to succeed and what good leadership required. In the past, Daniel had been successful as an action-oriented problem solver. He delivered results by knowing how to come up with the right answer and then rallying others around that solution. But now this approach and the underlying mindsets that drove it were no longer working for him.

When he was first offered the role of chief marketing officer (CMO) of the company, Daniel wasn’t sure that he wanted to take it. He didn’t feel a personal connection to the company’s products or mission, but it was a step up and ultimately too good an offer to refuse. Daniel tried to get excited about the business and knew that he would enjoy the creative and entrepreneurial aspects of the job. He was always up for the next big move, especially if it came with big challenges. That’s where he shined.

And challenges there were, but Daniel had the skills he needed to solve them, and for a while he remained mostly in a high-stakes Familiar Zone in a state of high performance. The parent company had paid a premium for this company because of its tremendous growth potential. When Daniel joined as CMO, the team increased their marketing spend, pushed aggressively into international markets, and invested in new marketing facilities and distribution networks to become less dependent on third-party suppliers.

At first, this plan worked. Despite aggressive growth targets, they were exceeding them each and every quarter. The business experienced double-digit growth each year and rolled out in many new countries around the world. It was a success story, and leaders from the parent company started flying in to learn how they had so quickly achieved such remarkable growth.

Then everything changed. One of the company’s top competitors came out with a new set of products based on what they claimed were game-changing scientific breakthroughs, and their philosophy and products were garnering an almost cultlike following. The competitor was successfully executing an aggressive promotional campaign aimed directly at the business Daniel had been building. Consumers voted with their purchases, and within only a couple of months, Daniel saw his company’s double-digit growth turn into a double-digit decline. Daniel had never seen or experienced anything like this before. Their competitor seemed to have created a movement that was catching fire across all their key market segments.

As the executive team struggled to digest the sudden and massive shift in consumer preferences, they could not agree on a way forward. Many people on the team were convinced that this was a passing fad, and the brighter the flame burned, all the more quickly it would burn itself out. But what if they were wrong? If this competitive threat was here to stay and they could not address it quickly, it could be catastrophic for the company, leading to layoffs and an inability to cover the fixed costs of their manufacturing investments.

When Adrienne, the CEO faced big decisions like this, she relied on her team to reach a consensus about what to do. As weeks passed and the competitor continued to eat into their market share, many of the team started feeling an urgent need to act, but they were still at an impasse. They simply could not agree on what to do. Daniel was also feeling increasingly frustrated with his colleagues for their inability to make decisions and get aligned.

Daniel felt like his head was spinning as he listened to the team going around and around in circles. No one on the team was listening to the other points of view as they insisted that their own position was the only feasible solution. And the more they debated, the more stuck they seemed. While sales numbers kept dropping and the parent company demanded to know how the executive team was going to address it, emotions in the boardroom ran high.

Meanwhile, continuous questions from the parent company were putting a lot of extra strain on the executive team. Yet, they remained stuck. The team members were really digging into their entrenched views. Every time a new piece of data came in, each team member used it to justify their own opinion. Their viewpoints became even more polarized, and their discussions grew longer, yet more contentious and less productive.

During this period, Daniel went skiing for a weekend and developed a severe sore infection. He was forced to stay in bed for a few weeks with a high fever. On the day he had planned to return to work, he woke up with severe muscle aches all over his body. He was tired and agitated, which was unlike him, and a few days later he started rapidly losing weight.

Doctors’ visits and labs revealed that Daniel had developed a runaway thyroid, the gland that regulates the body’s metabolic rate. As a result, he was burning around eight thousand calories per day (over three times the normal amount)! When the doctors asked what was going on in Daniel’s life and heard about the tense business situation he was caught up in, he gave Daniel a choice: he could either take out Daniel’s thyroid, which meant he would have to manage his metabolism with pills for the rest of his life, or he needed to address the stress, lifestyle, and behavioral factors likely causing his thyroid condition.

RADICAL ACCOUNTABILITY

Daniel choose the latter, and that was how he ended up in the room with Kimberly, the consultant and coach working with him to address his current challenges. Instead of focusing on the simple decision of whether or not to change the company’s products or marketing to increase sales, Kimberly focused on Daniel’s leadership style and behavior with the executive team and the underlying mindset that was driving his behavior, along with his emotional responses to the current situation.

Daniel’s first breakthrough came from understanding his own default leadership behavior in challenging situations. His proven success model of finding a solution analytically, largely on his own, and then convincing others to join him on the path forward was not leading to the desired alignment of the team. Daniel had assumed that the misalignment was because of his team members. After all, this was his first time dealing with a crisis in this particular company and the first time in his career that his proven success model wasn’t working. He figured that it must have been their fault and did not consciously investigate his own role in the crisis.

This is a challenge we often experience with successful leaders. They have a proven success model that has worked so well for them in the past that they have a hard time questioning it until they realize that they are in the Adaptive Zone and need to try something new. We believe that the way we are seeing things is objectively true, so we do not look inward and examine other possibilities or the way in which our point of view might be skewed. This leads us to blame others or circumstances outside ourselves for our problems instead of taking ownership and finding ways to change to create a better outcome.

Kimberly explained to Daniel that the first step toward finding a new success model was to develop deeper awareness about his current mindset and to discover why it was not effective in addressing his current challenge. What were the blind spots it was creating?

Once Daniel embraced the idea that he did not need to know the answer to be a good leader but rather needed to rally the team to collaborate on a journey of discovery. He didn’t have to wait for other people or external circumstances to change. He did not need to wait for Adrienne to decide or for the team to align or for all data to emerge. Now he could refocus on what he could control and change in order to improve things – himself. This felt incredibly empowering and opened up the space for Daniel to explore new mindsets that would allow him to play a different role in resolving the crisis.

After building awareness and acceptance, the next step was for Daniel to make the choice to change. After a great deal of reflection and answering Kimberly’s questions, Daniel developed an alternative mindset that he was willing to try out. His mindset changed from, “To be a good leader in this challenge, I have to know the answer and people need to follow me,” to, “To be a good leader in this situation, I need to collaborate, listen to all the different perspectives, and support people to come to a collective decision.”

Once he had a clearer sense of the different perspectives, Daniel brought the various opposing views into the room together and worked on helping the team to really hear each other before debating solutions. He helped facilitate a number of “what if” scenarios to pressure-test the various ideas and assumptions behind the different positions. And he encouraged the others to do the same, inviting colleagues to get curios and ask questions to gain deeper understanding and broader perspective. This led to a much more creative process of solution finding, where people could air their emotions, thoughts, and deeper beliefs without being interrupted.

Eventually, the company’s decline in revenue stabilized, their cost base was adapted, and the team started to look for adaptations in their product range to address the consumer needs that their competitor had tapped into. Daniel was incredibly energized by his ability to facilitate the collective leadership of others to make this progress. All of this was unlocked by gaining awareness of his default mindset and making a conscious pivot. He dove into additional work with Kimberly, and continued uncovering blind spots, growing further in self-awareness and personal mastery.

After spending a lot of time reflecting on this, Daniel realized that there was a clear connection between his health and work crises, there was a third crisis babbling up behind the scenes, and there was a dynamic interplay among all three. Ambition is finite while purpose is not. And since Daniel’s connection to his career had been based primarily on ambition, the energy it had given him all of these years was finally running out.

WHERE OUR PASSION MEETS THE NEEDS OF THE WORLD

The mystery of human existence lies not in just staying alive, but in finding something to live for.

—Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Everyone benefits from living with a sense of purpose. As part of the foundational layer of our icebergs, our purpose in life creates a large piece of our identities and drives everything above it. Many of us find this type of meaning in multiple roles and areas of our life. Many people are fulfilled for living out their purpose outside work. But for those of us who aspire to high levels of performance, connecting our work to a deeper sense of meaning helps us perform better, gain energy, and more easily shift into a sense of learning when we find ourselves in the Adaptive Zone.

When we are connected to a deeper sense of purpose, we are healthier, we are more productive, we are more resilient, and we are more tolerant in the face of change and uncertainty. People who say they are “living their purpose” at work report levels of well-being that are five times higher than those who say they are not. The boost in health and well-being that comes from living with purpose can have a dramatic impact on our entire lives – and even how long we live.

Perhaps no one has written more poignantly about the importance of purpose than psychiatrist Viktor Frankl. His book Man’s Search for Meaning chronicles his experiences as a prisoner in four Nazi concentration camps during World War II. After losing his parents, his brother, and his pregnant wife in the camps, observing how other prisoners coped, and later treating many of his fellow prisoners after they were released, Frankl came to believe that maintaining a sense of meaning even in the darkest times plays a pivotal role in how we experience trauma and even in how likely we are to survive. He found that the prisoners who were living for a specific purpose had a better chance of survival than those who were not, regardless of their specific circumstances. After the war, Frankl went on to develop his own method, called logotherapy, founded on the principle that finding meaning in life is our most powerful driving force as humans.

In addition to the physical, mental, and emotional benefits to connecting to a sense of purpose, it is also a meaning-making opportunity. We already know the impact that our mindsets can have on our ability to lead and perform within the Adaptive Zone. Likewise, connecting to a sense of purpose allows us to rewrite our personal narratives about what is happening to us and why. It shifts our mindsets by offering us meaning that makes stress and challenges worthwhile and expands our tolerance for change. In other words, it helps us frame adaptive situations more positively.

When we are able to tell ourselves that we are doing something difficult because it is serving a bigger and more important “why,” we anchor ourselves in a positive context and narrative that creates an inner sense of courage and safety.

Even if the activity we are doing in this moment is not going well, or not going according to our expectations, we can see it as a bump on the road that will get us to our ultimate destination.

When framed within this broader perspective, even extremely effortful work feels more rewarding and less challenging. This method of “feeding” ourselves a positive message, especially when facing difficulty, is an emotional regulation tactic that keeps us from being swept away by emotion when facing challenges at any level. In the face of change or turbulence, our purpose can act as an anchor that keeps us rooted to who we are and what we stand for. No matter what is going on around us, we are able to remain steady and constant as we look out at that dot on the horizon and remember where we are headed.

Without the dot on the horizon to aim for, we are so much more likely to shift to protection. We don’t know what we really want, so we act to protect what we already have. This leads us to become reactive, looking for problems to solve instead of opportunities to innovate. This is especially important when we are in a high-stakes Adaptive Zone. Without a sense of purpose in this context, we are like a ship at sea in a storm with no destination and can only react to the next wave that is hitting us instead of proactively striving forward.

CONCLUSION

One can choose to go back toward safety or forward toward growth. Growth must be chosen again and again; fear must be overcome again and again.

—Abraham Maslow

In 2018, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau said, “The pace of change has never been this fast, but it will never be this slow again.” In our increasingly VUCA – volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous – world, old methods are crumbling and new ones seek to emerge, and as leaders we must continuously adapt to create a new reality that we will be proud to leave for the next generation. For each of us, this adaptation may play out in different levels in our lives: in our families, in our teams and organizations, in our countries, and in the world.

None of us knows what disruption or change is lurking around the corner. But we do know that as the world changes, it will continue to become more and more important for us to adapt and more and more difficult to do so.

What the world needs now are leaders who can also be learners even in the most challenging circumstances. To become this type of learning leaders, we must expand our consciousness so we can break through the habits that keep us tied to the past, see the world with fresh eyes, and open up new ways of relating to each other and the changing world.

This means that it will never be easier than it is today to start practicing Deliberate Calm. Doing so will help you unlock the adaptability paradox so that you can learn, adapt, thrive, and succeed no matter what is going on around you or what challenges you may face. If you are not currently in the midst of a disruption or crisis, it may seem like there is no reason to start practicing Deliberate Calm now. But this is actually the perfect time to start building this muscle to prepare for the future’s unknown. If you are currently facing a major change or challenge, it may seem like you have no time to integrate new practices into your life. But there is always enough time to pause before reacting and to make a deliberate calm choice, and in this context, slowing down now means speeding up later. We can encourage you to start applying these techniques however you can right now, no matter what is going on for you personally or professionally.

To be effective, leaders must always be learners. You can never arrive – you can only strive to get better.

—John C. Maxwell

Think back to Captain Sullenberger, whose story was used to open this book. He had mere seconds to decide whether to follow the existing playbook and return to the airport or to adapt to the situation he was facing and try something new, and he made those seconds count. You now possess all of the tools you need to master your emotions and leverage all of your resources to choose the best possible response regardless of what you are facing.

Simply practicing Deliberate Calm will have an impact on those around you. You also have an opportunity to teach these skills to others, creating a ripple effect among your family, your teams, your community, and ultimately the world. The authors wrote this book grounded in the optimism that with greater awareness, we can rise together to meet the challenges of the future with compassion, confidence, and hope.

///end

If you have any comments on our book digest series, please drop us a note aboitiz.eyes@aboitiz.com